December 17, 2020

From the Vault: Seaweed Intrigue

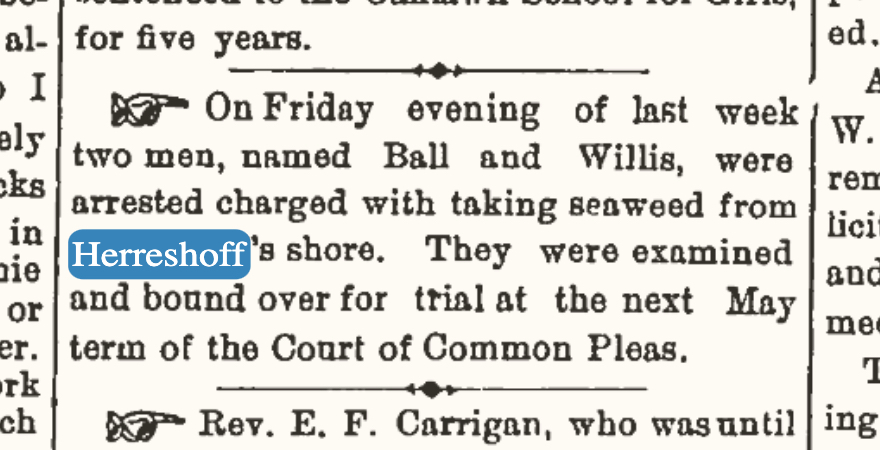

News of two 1889 arrests on HMCo.'s waterfront leads us down a peculiar Rhode Island rabbit hole

An Odd Arrest

This week's "From the Vault" post was motivated by a brief Bristol Phoenix report published 131 years ago this week. As sometimes happens with these HMCo. mentions in the Phoenix, this piece immediately brought many more questions to mind than answers! So we thought we'd investigate: What significance would "collecting seaweed" have had to the general public and readership of the Phoenix in the 1880s? What did these two men intend to use the seaweed for? Why would anyone collect seaweed in December? Was it worth getting arrested over? What was illegal about all of this? Was "collecting seaweed" code for some other nefarious activity?

Why Collect Seaweed?

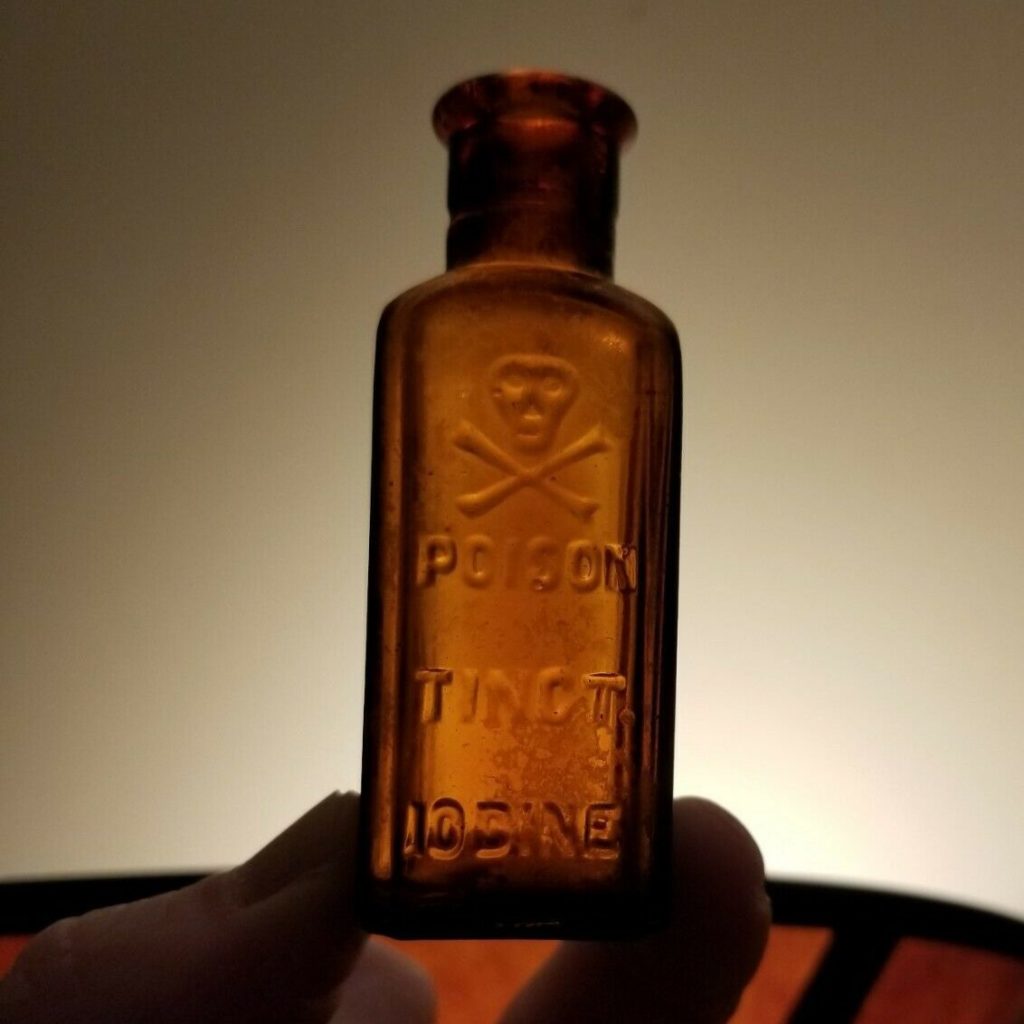

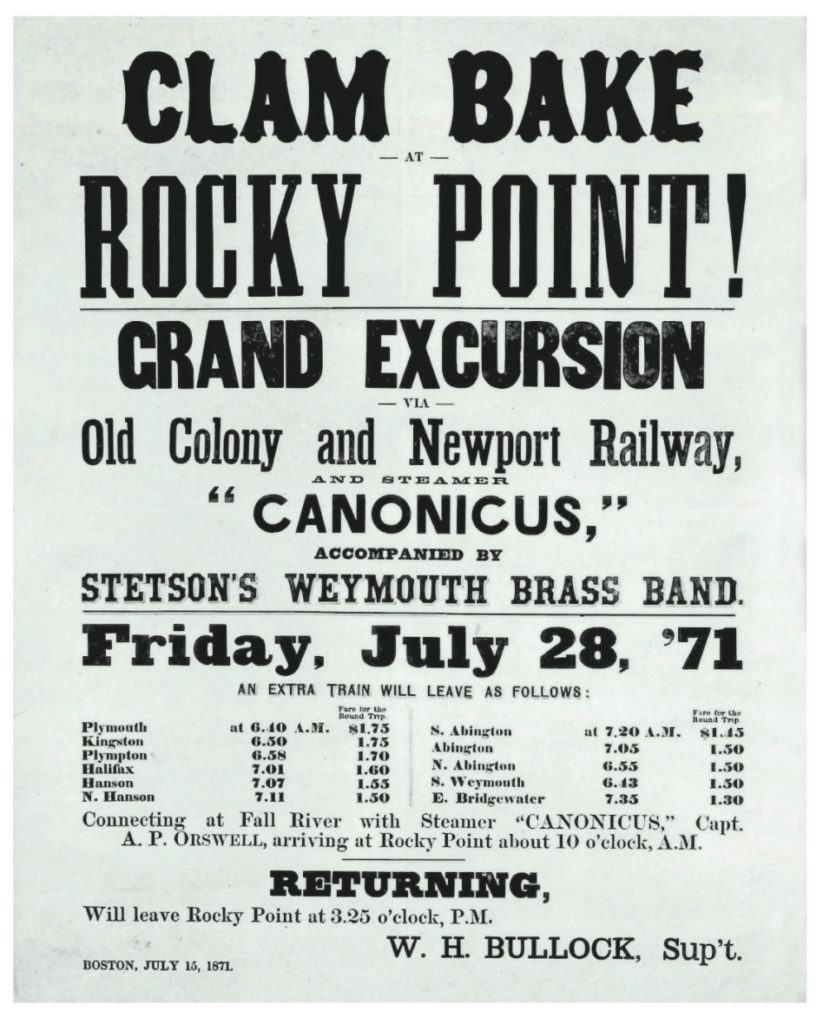

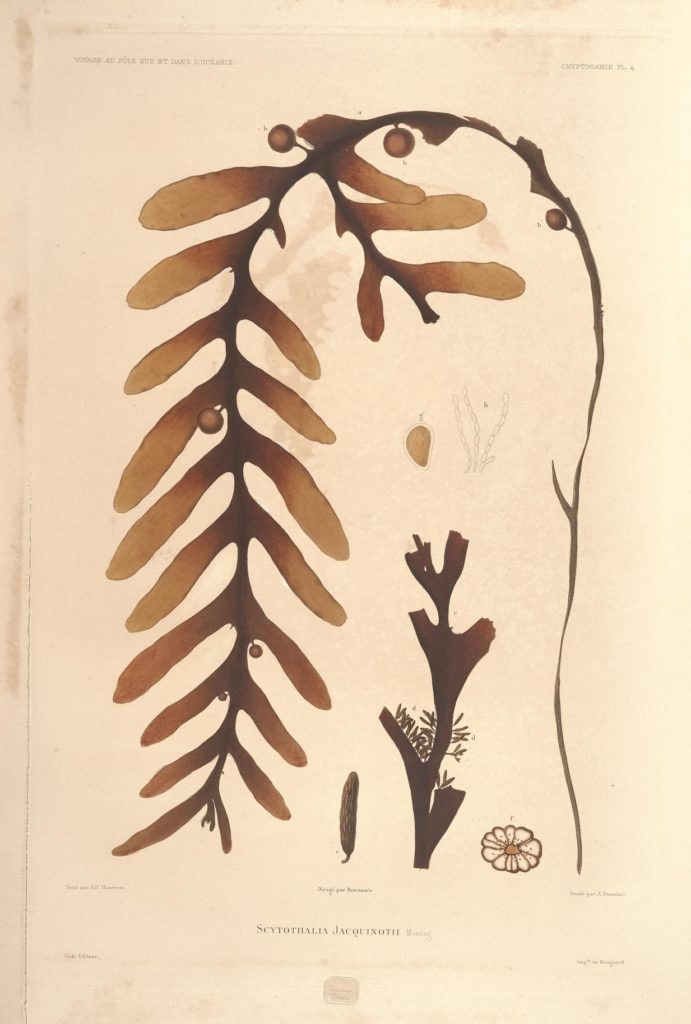

Globally, seaweed has been harvested for thousands of years and for countless purposes. Historically it was used as livestock feed in some regions, while elsewhere it was burned for fuel. Various species have been a dietary staple in numerous cultures around the world throughout history. Seaweed has long been used as a form of cooking technology close to home for us at HMM: the traditional "New England" clambake traces its origins to the cooking traditions of the indigenous coastal tribes that inhabited this region for millennia before the arrival of European settlers. Seaweed's potency as a fertilizer has likewise been known for thousands of years. Potential applications for this ubiquitous commodity only broadened during the Industrial era. Soda formed from burning seaweed was used in European glass and soap production in the 18th century. In the first half of the 19th century, this cheap and accessible source of soda and potash proved key in the production of saltpeter for gunpowder and explosives during the Napoleonic Wars. The discovery of the new element iodine in 1811 was a by-product of seaweed processing for saltpeter production. Within ten years, iodine's antiseptic qualities were identified. Iodine's medicinal properties when ingested were simultaneously under exploration, ranging from the genuinely effective (in the treatment of thyroid disorders, for example) to widely advertised and extremely dubious seaweed-based snake-oil cure-all's. Between 1820 and 1840 iodine was marketed for every conceivable medical application, some more effective than others. There was even a booth in the 1851 Crystal Palace Exhibition dedicated to the substance and its broader chemical applications, such as in early photography.

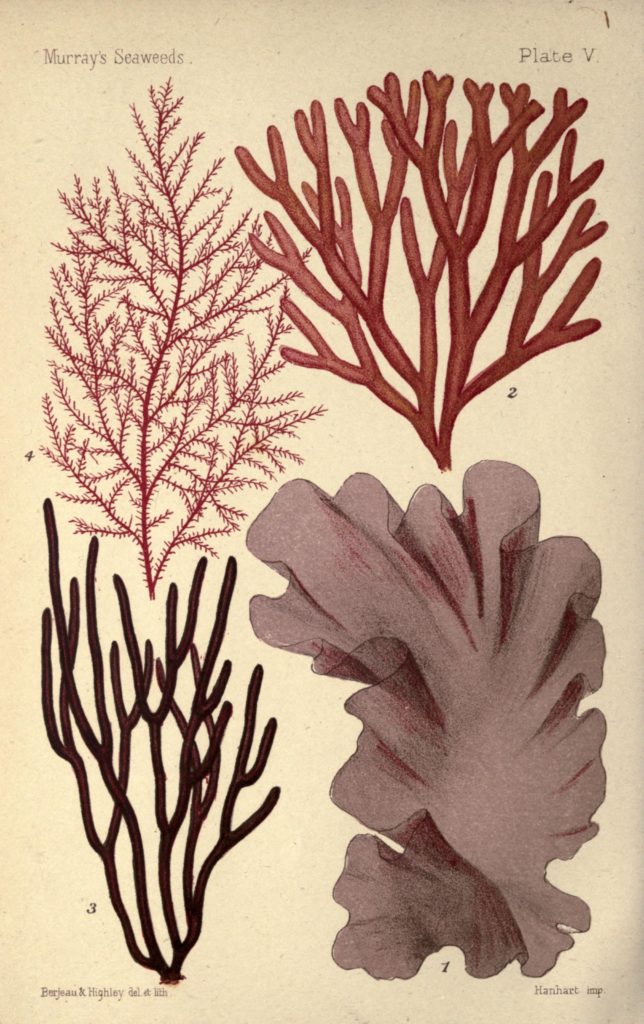

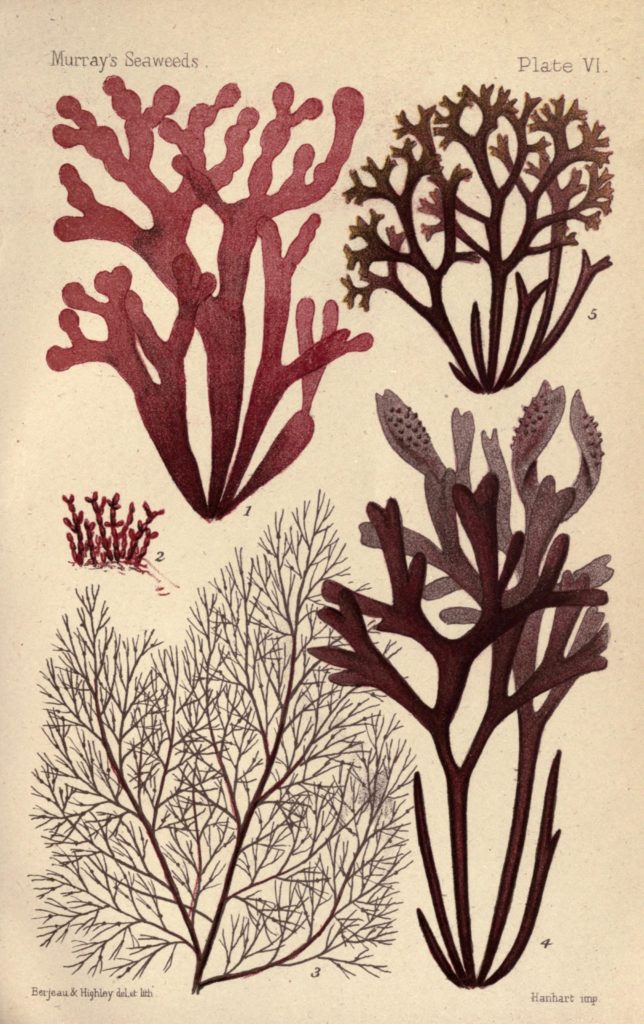

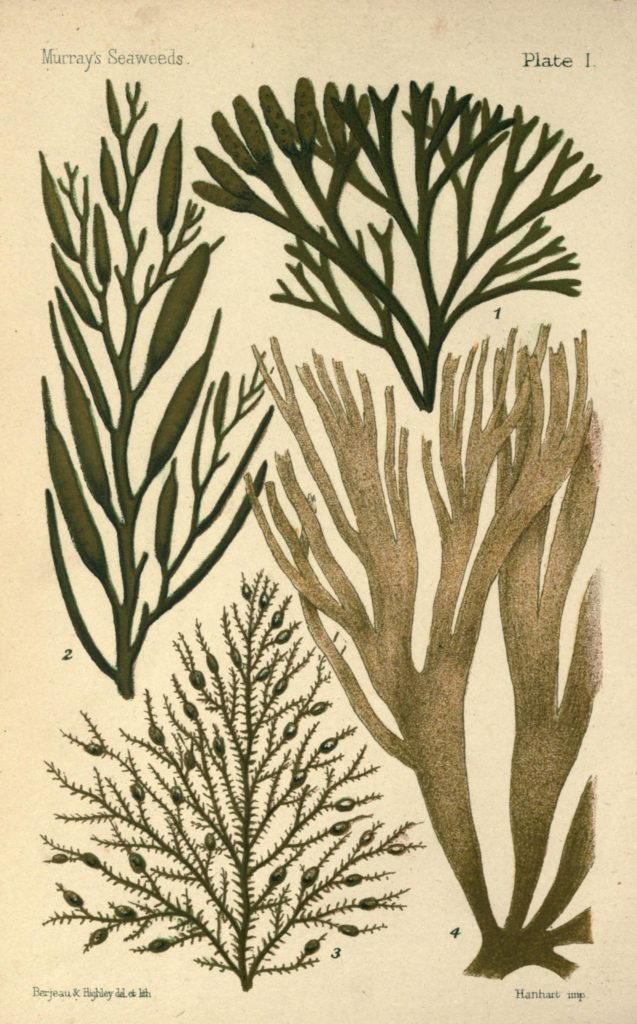

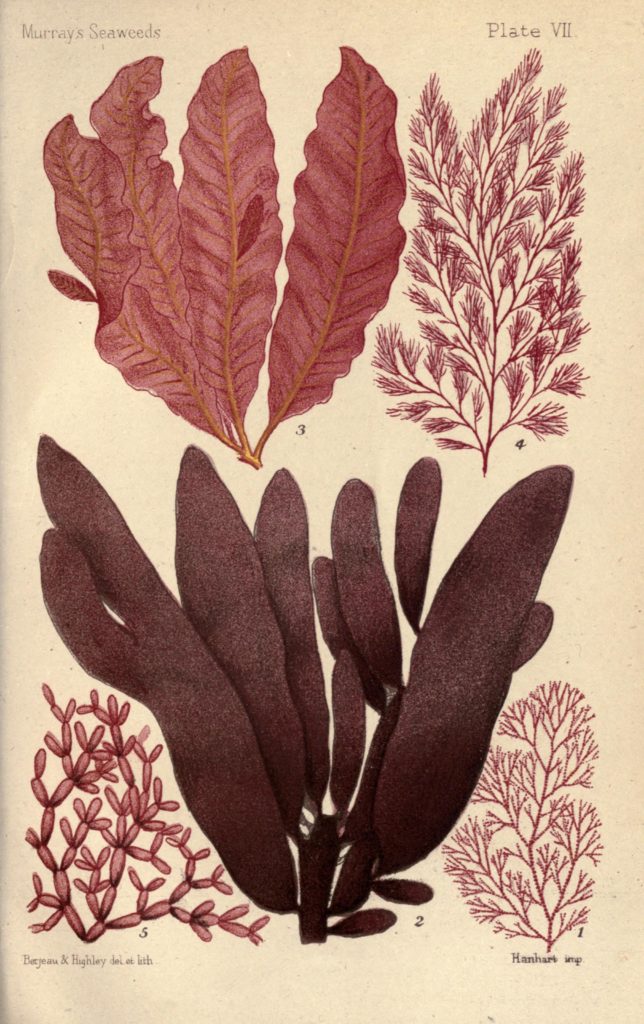

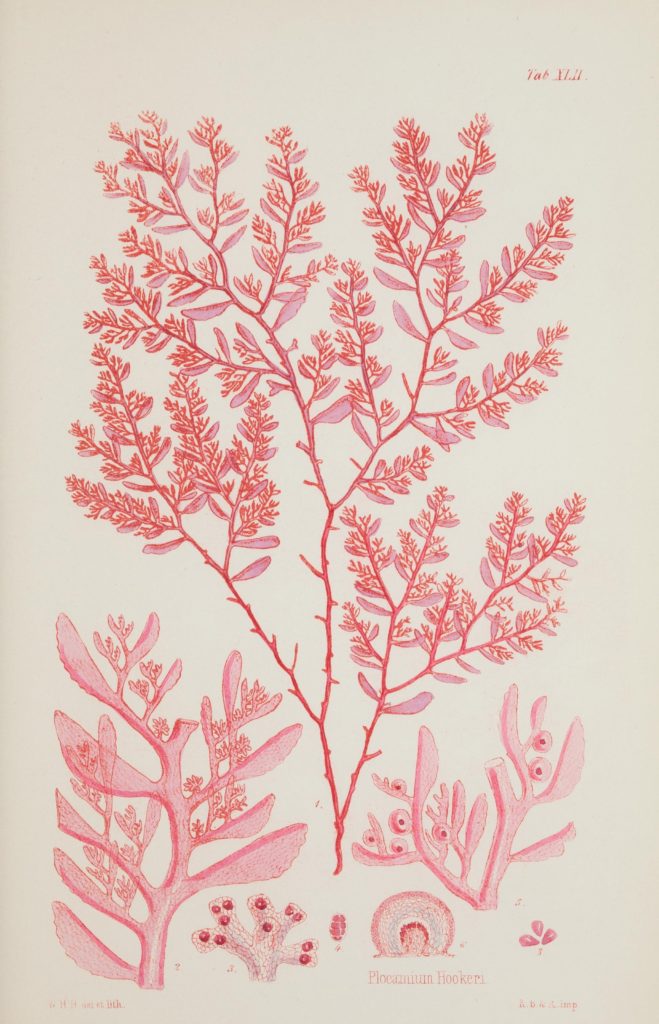

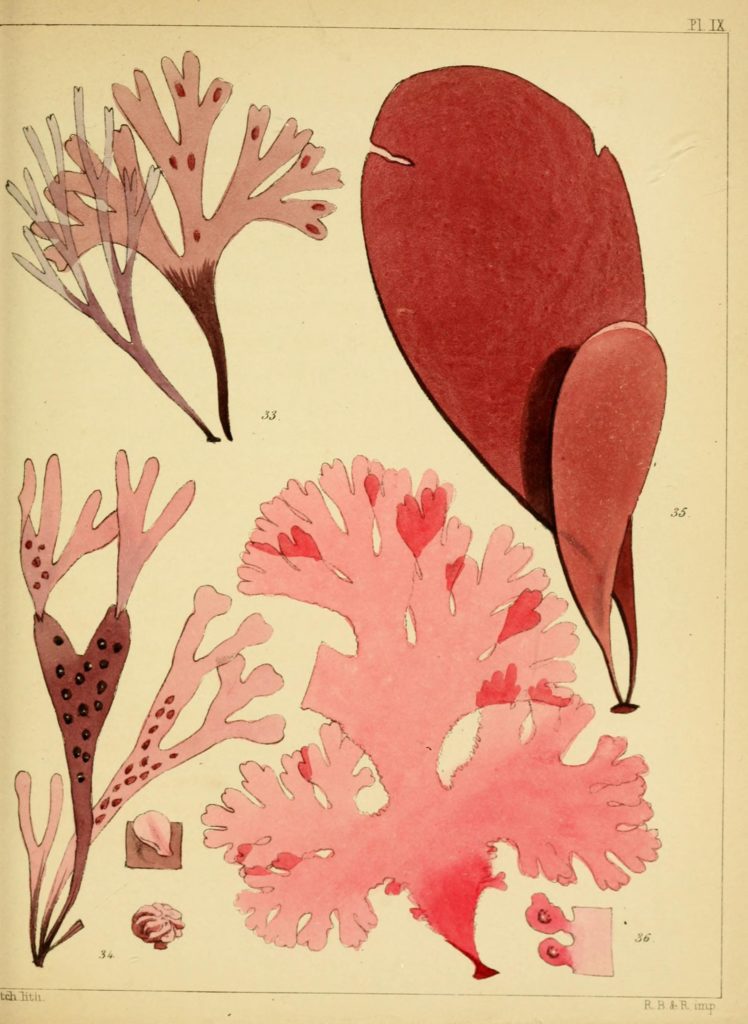

Apart from its broad industrial, medicinal and dietary uses around the world through the ages, seaweed was enjoying particular popularity in Europe as a focus for recreation in the mid 19th century. For example, documenting coastal specimens was not just a thing for scientists in the Victorian era: it also was in-vogue among the public, and seaweed collection, preservation, and identification really took off with the ladies during this period for... various reasons. (Check out this related "From the Vault" post on the history of cyanotypes and blueprints!) Another form of recreation involving seaweed during the 19th century in the U.S. was the adoption of the increasingly popular "New England" clambake. Though its indigenous origins were a utilitarian and practical form of cooking technology, in the 19th century a clambake was as much a social event as it was a meal - if not more.*

A Brief History of Shore Privilege in RI

Stickier than the question of "what is seaweed good for" is the question of "who has the right to harvest seaweed, where, and how?" It is not unrelated the 19th and early 20th century oyster wars in the northeastern U.S. The sedentary nature of oysters especially lead to all sorts of guerrilla warfare, nighttime skirmishes, and extreme boat design evolutions to patrol and stake out plumb territories in shallow offshore regions that no one could legally own but plenty of folks had a vested interest in. (If you want to learn more, we highly recommend Oystering from New York to Boston by John M. Kochiss ). But that's a whole other story! To greatly simplify the issue of littoral rights in the U.S. - ownership of land under a lake or ocean's surface - nowhere can you own land below the mean low tideline. Who is allowed access to that space between low and high tidelines varies state by state and consequently fisheries rights along the intertidal zone have long been controversial. In the case of seaweed harvesting, where does private property end, and where does public access begin?

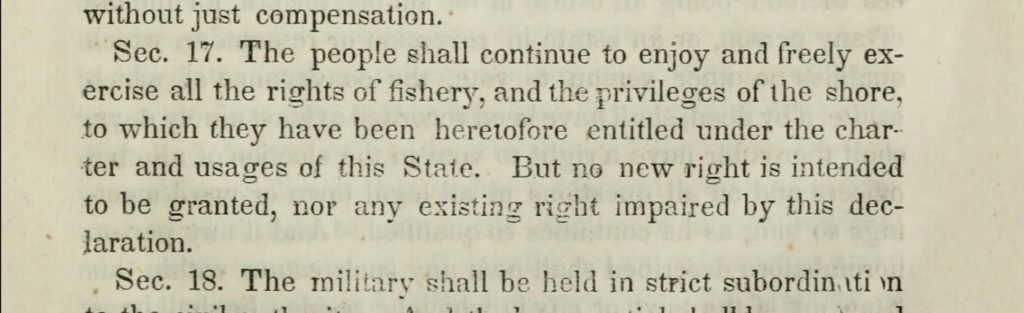

In Rhode Island, the history of guaranteeing shore fisheries access goes back to the Colonial period and the original 1663 Charter, which stated that the Colonial government of RI "shall not, in any manner, hinder any of our loving subjects, whatsoever, from using and exercising the trades of fishing upon the coast, in any of the seas thereunto adjoining, or any arms of the seas, or salt water, rivers and creeks, where they have been accustomed to fish; and to build and set up on the waste lands belonging to the said Colony and Plantations, such wharves, stages and workhouses as shall be necessary for the salting, drying and keeping of their fish to be taken or gotten upon that coast." The Charter stood until the adoption of Rhode Island's Constitution in 1843, which referenced the original Charter fisheries clause explicitly in Section 1, Article 17: "The people shall continue to enjoy and freely exercise all rights of fishing and privileges of shore, to which they have been heretofore entitled under the charter and usages of this state..." In 1970 this was amended for a more conservation-focused statement, and in 1986 "usages" was expanded to include "fishing from shore, the gathering of seaweed, leaving the shore to swim in the sea and passage along the shore." You can read more about the history of amendments to RI's Constitution here. Today seaweed gathering is literally a Constitutional right in Rhode Island! But it was not explicitly so in 1889.

Ball and Willis

But back to our pair on the HMCo. shore. Why were they collecting seaweed in December? We can only speculate, but a seaweed scrapbook and a December clambake both seem equally unlikely even if it was unseasonably warm that December as N.G.H.'s diaries suggest. Truthfully, the scrapbooking fad was pretty much done by this time period, and was never as popular with the gentleman anyways. The Bristol Phoenix seaweed snake oil ads had petered out by this time, so they probably weren't aspiring entrepreneurs in that sense. Large quantities are required for iodine and explosives, and alternative sources for potash and soda had been identified by the late 1800s. That leaves collecting material for fertilizer or some kind of fill application as the likeliest conclusions, though both of those still seem like thin explanations - how much could two men collect on HMCo.'s relatively meager length of shoreline? We may be forced to consider that even after all this littoral digging, it is possible that "seaweed collecting" was simply the excuse given to the HMCo. watchman who caught two suspicious characters snooping at the tideline. So what else was going on at HMCo. in December of 1889, that two strangers might be interested in? What would have been nearly completed and poised to launch on January 23, 1890? That's right: HMCo. #152, the one and only CUSHING, Torpedo Boat #1 for the U.S. Navy. Perhaps, despite its many very useful applications, Ball and Willis weren't after seaweed after all?

*For the record, HMM loves clambakes and generally disagrees with all opinions expressed by that author in this Bristol Phoenix article