July 9, 2020

HMCo., Blueprints and Cyanotypes

From the technical to the creative, how was blueprinting and cyanotype technology employed in and around the shops at HMCo.?

An Introduction

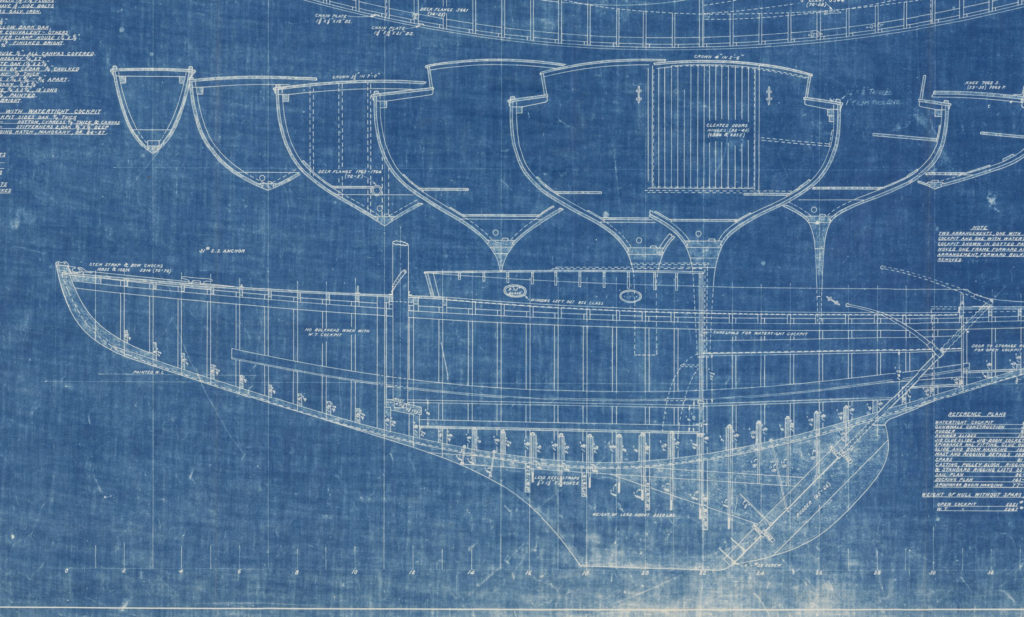

We frequently get enquiries at the museum about "original blueprints," or see listings on eBay using the same phrase. Today, unless you worked in a drafting office in the pre-computer days, most people see that iconic white-on-blue color scheme and they automatically think that is the origin of the design, the first thing that was produced, and the primary output of a drafting office: in other words, an original document. But a blueprint by its very definition is a copy of an original drawing. Though it is an understandable line of thinking, the phrase "original blueprint" is a contradiction of terms. Before (or more accurately, on top of) every blueprint you've ever seen, there was once a beautifully drafted, ink on paper or starched linen, painstakingly executed drawing. However, this confusion of terms does not make blueprints any less exciting or interesting as artifacts. It also provides an opportunity to talk about the drafting process, and the business of running a vertically integrated company like HMCo. Today we will briefly discuss the history of blueprinting, how it was used at HMCo., and where else examples of the same chemistry and technology turn up in the Herreshoff story.

How does it work?

Blueprinting was a very efficient method for making copies before the days of diazotypes and xerography. The process became widely adopted in the late 19th century, and was an especially useful method for reproducing large engineering and architectural documents at 1:1 scale. It is a contact printing process, which means that prints are made by taking a chemically treated piece of unexposed blueprint paper and laying it under (in "contact" with) the original drawing being copied. A piece of glass is placed on top to keep everything flat, and the stack is placed in the sun to be exposed. Because the chemical coating on the blueprint paper is light sensitive, when UV rays shine through the blank areas of the original drawing, the exposed blueprint paper below turns blue. The light is blocked by the inked lines, which is why they remain white.

A very short history...

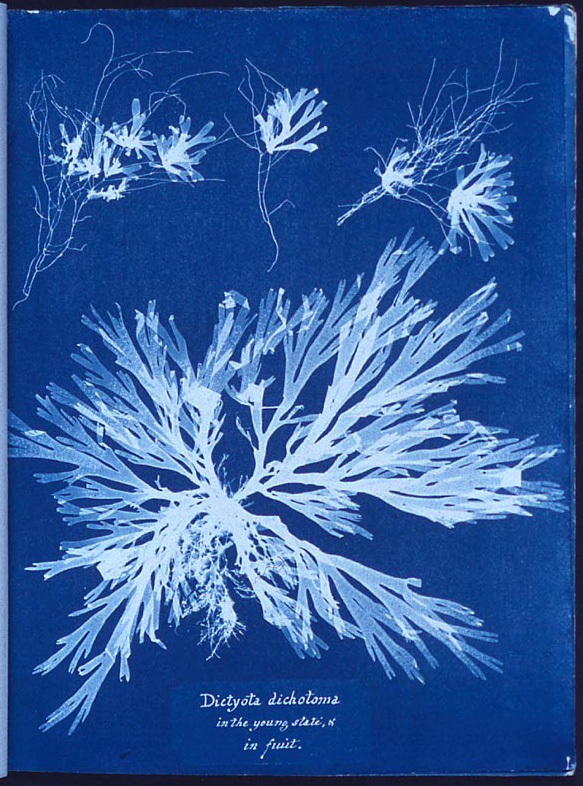

Blueprints and cyanotypes are both produced with light sensitive iron salts. Both processes were made possible by advances in the study of chemistry during the Industrial Revolution, and are closely connected with the origins of photography. The difference between blueprints and cyanotypes is largely defined by the subject matter: drawings and notes in the case of blueprints, and objects and later photographic negatives in the case of cyanotypes. The discovery of the process is credited to English scientist and astronomer, Sir John Herschel in 1842, who mostly used it to copy notes and diagrams. He was friends with a woman named Anna Atkins, who was a botanist. In 1843, within a year of Herschel's discovery, Atkins used the technology to create cyanotype prints for a book on algae - or, "photo-graphs" as in, "light drawings." (Today, a blueprint or cyanotype is sometimes also referred to as a "photogram" when it was produced without the use of a camera). By placing samples of plants and algae over the photo-sensitive paper, Atkins was able to create images of the specimens as light filtered through and around them. Partly as a result of this work, Atkins is known today as one of the earliest female photographers. Her prints are as beautiful as they are interesting to look at, and you can find digitized versions of the book in rare book archives online today.

Blueprinting technology was more widely adopted by engineering professions in the 1880s and 1890s, and was extensively employed through the mid 20th century. It was an extremely fast, cost effective, simple and accessible method for reproducing large technical drawings without damaging the originals. It also produced copies that were relatively stable by the standards of a working architectural or engineering firm's timelines. As they age, blueprints do tend to become brittle and more fragile, but in the short term if properly washed with water in the developing process, they are quite color fast and stable.

Blueprinting at HMCo.

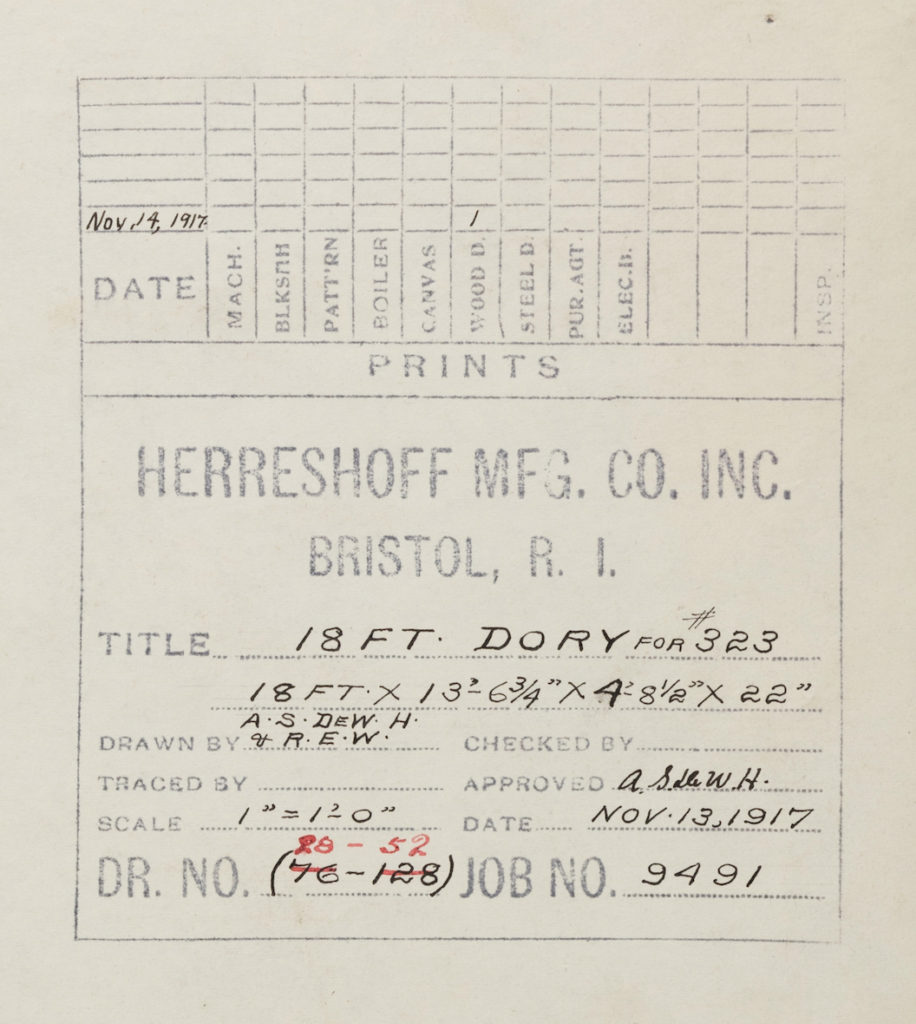

Blueprinting became an important part of running a hugely complex business like HMCo. as the company expanded. The drafting office was the center of the operation and had to communicate instructions for execution of these designs for everything from cleats to sails to hundreds of employees operating across departments. Even so, HMCo. was able to consistently produce a tightly controlled, highly engineered, high performance product. Blueprints helped enable this. The original drawings in the drafting office overseen by N.G.H. for most of his life, and later by his son and chief designer A. Sidney deWolf Herreshoff, were the closely guarded intellectual property of the company. Part of what made HMCo. so efficient was the reuse of the same elements over and over again in their designs - for example, hardware, deck furniture, paneling etc., was frequently adapted or reused on vessel after vessel. We see this in annotations on the drawings themselves indicating other vessels and job numbers. Not only was this very efficient but it also gave Herreshoff built boats a unified aesthetic that is still very identifiable today. So, to protect the original drawings from getting destroyed or lost in the shops, copies had to be made. We do see a few examples of very early drawings having been copied and redrafted by hand in the Herreshoff Collection at MIT, usually in cases where the original drawing is too lightly drawn, too fragile or too dirty to have been otherwise copied - but what we see much more commonly is note after note on hundreds of drawings referencing the production of blueprints.

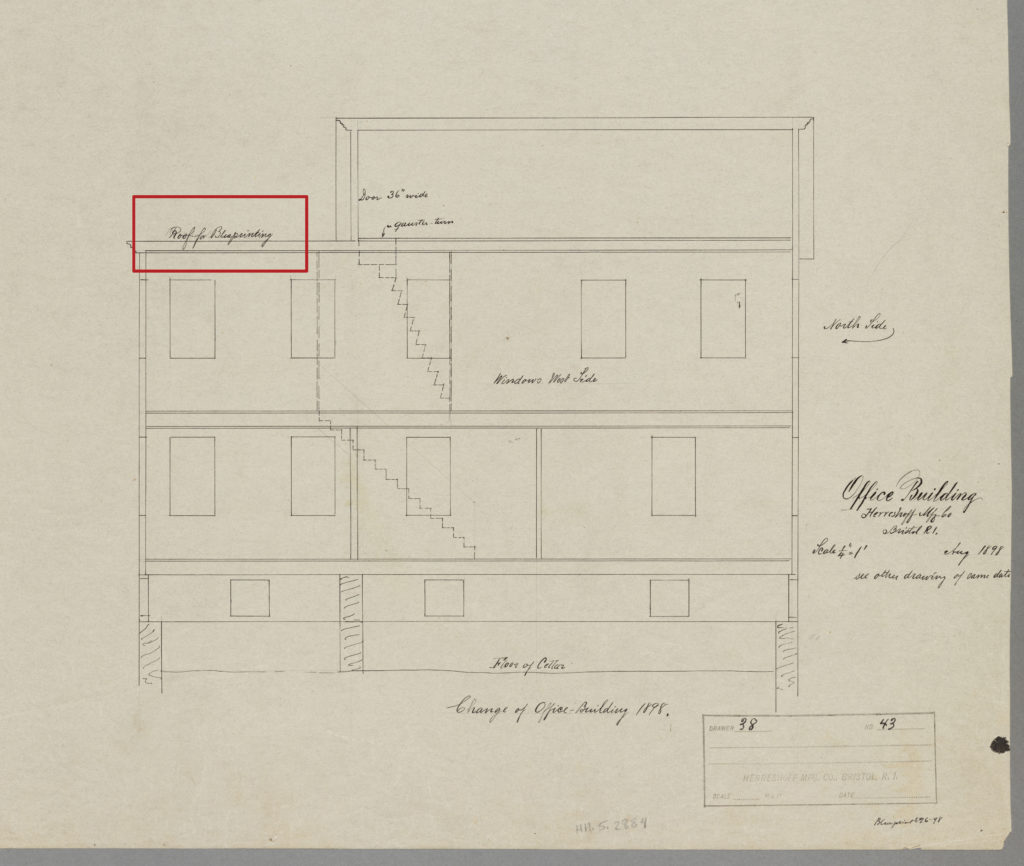

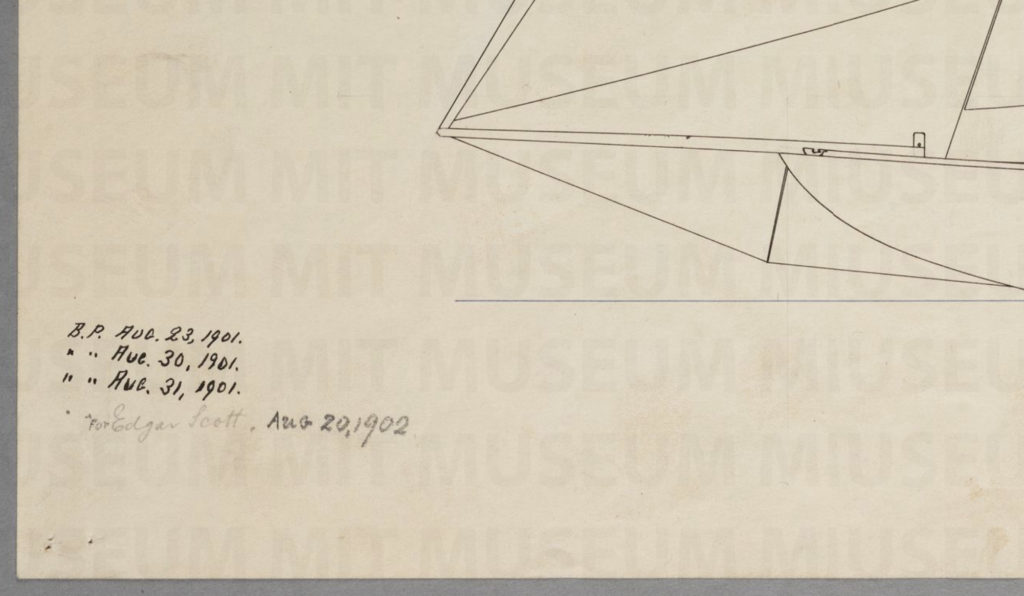

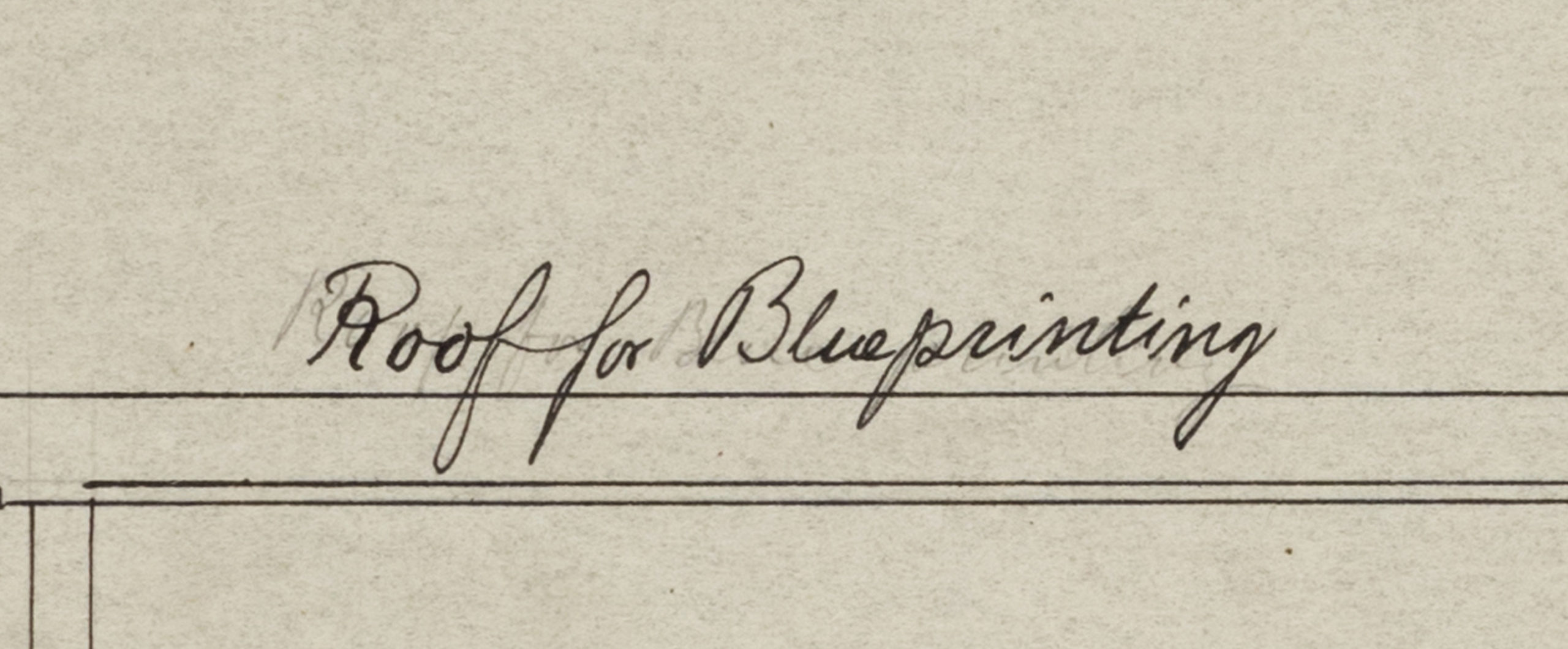

The Herreshoff drafting department made blueprints so often they had a dedicated balcony on the roof of their office building to lay the drawings out for exposure. We know this because it is actually indicated on the plans for the building (which they also designed themselves! see above). Through notes on their original drawings, the drafting office kept careful track of how many blueprints they made, who or what other department at HMCo. they were made for, and sometimes, when or if the copies were destroyed after they were done with them. This information was usually recorded on the original drawing, first as a note in the margins, and later in tables that became increasingly detailed. The Herreshoff brothers were notoriously protective of their designs, and overall the changes to tables may indicate an increasing desire for control and need for increased bureaucracy as the Company grew.

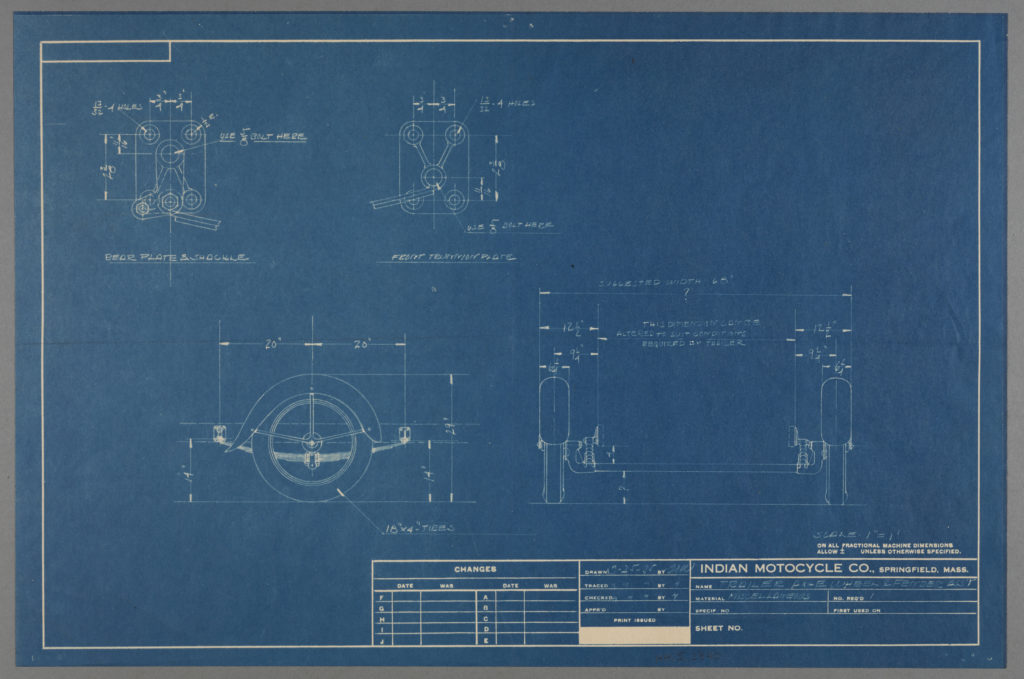

When we talk about the plans archive at MIT, the first question is often, "so, you're working with a lot of blueprints?" People are often surprised when you reply, "no, very few actually." Today, somewhat ironically, HMCo.-produced blueprints actually are pretty rare within the scope of the Haffenreffer-Herreshoff collection at MIT. While we see evidence that hundreds - maybe even thousands - were produced through notes on original drawings, relatively few have survived with the original drafting office archive, and they make up a small portion of the overall extant collection today. Partly this may be due to their intentional destruction, but more likely dispersal and wear and tear once the drawings went out into the shops meant that few survived. There probably wouldn't have been any reason to return them to the drafting office after the fact, and most examples we have from the archive are of plans that were used over and over again - so making a copy for the office made sense to reduce wear and tear - drawings that came from outside firms (like the Indian Motorcycle drawing above - more notes on that here if you're curious) or cases where changes were made to a drawing and it required outside approval, such as with wartime or Federal contracts. Thanks to analysis from the creators of the HCR, we know the earliest extant HMCo. produced blueprint in the MIT collection was produced in 1888. That said, we don't see a significant increase in blueprint production until 1895. Now that all of the Haffenreffer-Herreshoff collection drawings at the MIT Museum have been digitized and most of the drawings are online (if somewhat buggily, it still seems) we invite you to do your own hunting too!

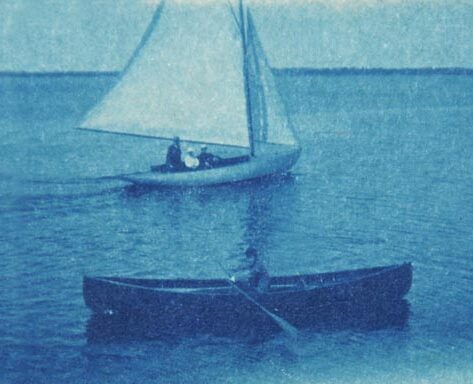

Cyanotypes and a family of photographers

On the other end of the spectrum from the architectural blueprint, we have a small number of examples of photographic cyanotypes in the historic photo collection at HMM. These look more like photographs in the conventional sense than blueprints. These were produced using the same light sensitive, ferric salt impregnated paper in contact with large format negatives. These prints were made from negatives taken by Herreshoff family members - most notably, photos from N.G.H.'s daughter Agnes M. Herreshoff's family photo albums. It is tempting to wonder whether or not she convinced the drafting department to slip her some scraps of blueprint paper for her own purposes, but we cannot know for sure. Irrespective, her photographs are a source of unusual small informal moments, detail and delight, and we will be publishing more of them as we continue to digitize the archives at HMM.

Today the cyanotype/blueprint lives on mostly as a kids craft activity. You may remember having gotten one of those little square lightproof packets as a kid, and laying it out in the sun with plants and leaves. You can still buy blueprinting/cyanotype paper today! If it's something you'd like to revisit with your own kids, or if you'd like to try your hand at developing your own cyanotype photographs at home, check out the resources on our At Home Activities post on the same topic.

This post is fondly dedicated to Kurt "There's-no-such-thing-as-an-original-blueprint" Hasselbalch, Curator Emeritus, Hart Nautical Collection, MIT Museum, and with apologies to Jon Duval, Architectural Historian, formerly of the Architecture Department, MIT Museum. Note: this post was edited on 7/16/20 to reflect updated analysis of the dates of HMCo.'s early blueprint production