July 21, 2022

From the Vault: The ARIA

A tribute to Roger C. Taylor, excerpted from his book "More Good Boats"

By Roger C. Taylor

This is a re-print of Roger C. Taylor's piece on ARIA (ex WHITE CAP, HMCo. #738), as it was published in More Good Boats (1980). The author's permission to share this and other essays is gratefully acknowledged. You can read his essay on the Herreshoff 15-footer in a previous post here.

Length on deck: 32 feet 3 inches - Length on waterline: 25 feet 4 inches - Beam: 8 feet 9 inches - Draft: 3 feet 1 inch - Displacement: 4 1/3 tons - Designer: Nathanael G. Herreshoff

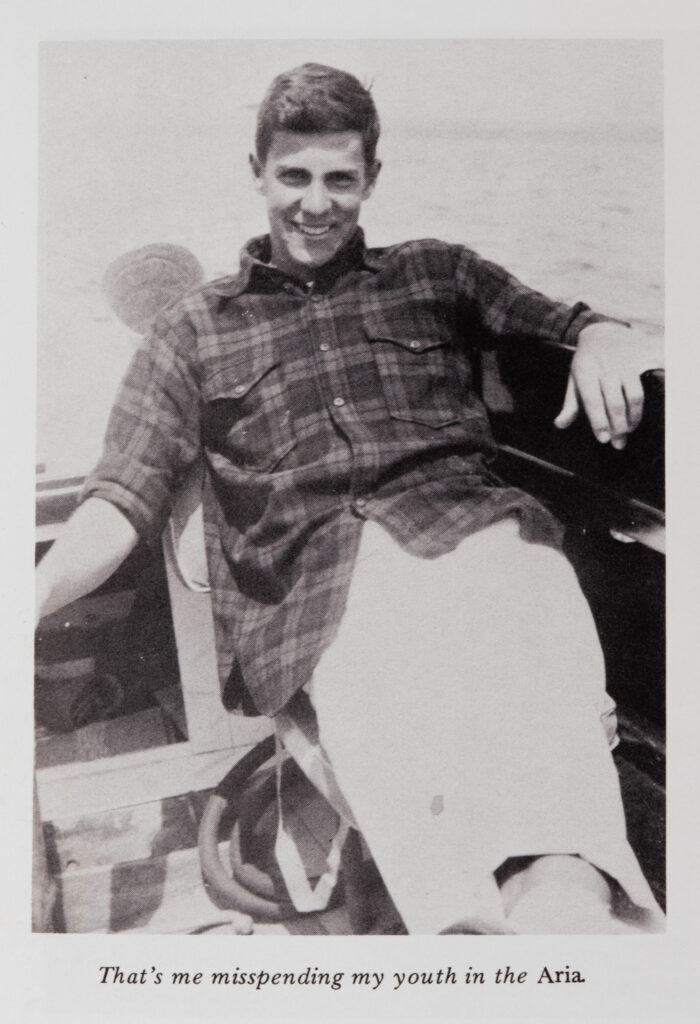

Pop swapped the yawl Brownie for a Herreshoff Buzzards Bay 25-footer, the Aria, in the fall of 1948. As in the case of all even swaps, each party thought he had the best of the deal. The Brownie was described in Good Boats and the Aria is described right here, so you can judge for yourself.

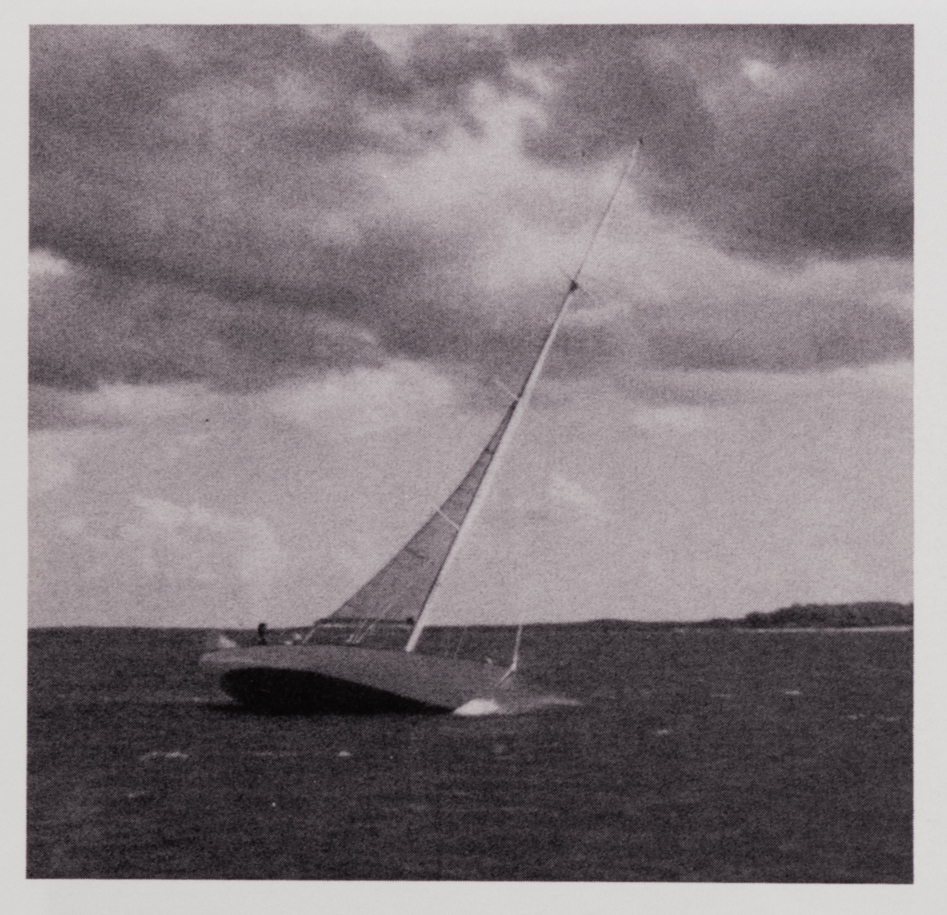

In any event, Pop never got to capitalize on the arrangement; the following spring he got the new boat overboard but died before he could take her sailing the first time. So the Aria became my legacy, and I guess no 17-year-old whipper-snapper ever had better. I kept her ten years and never could get used to her speed. She is some boat.

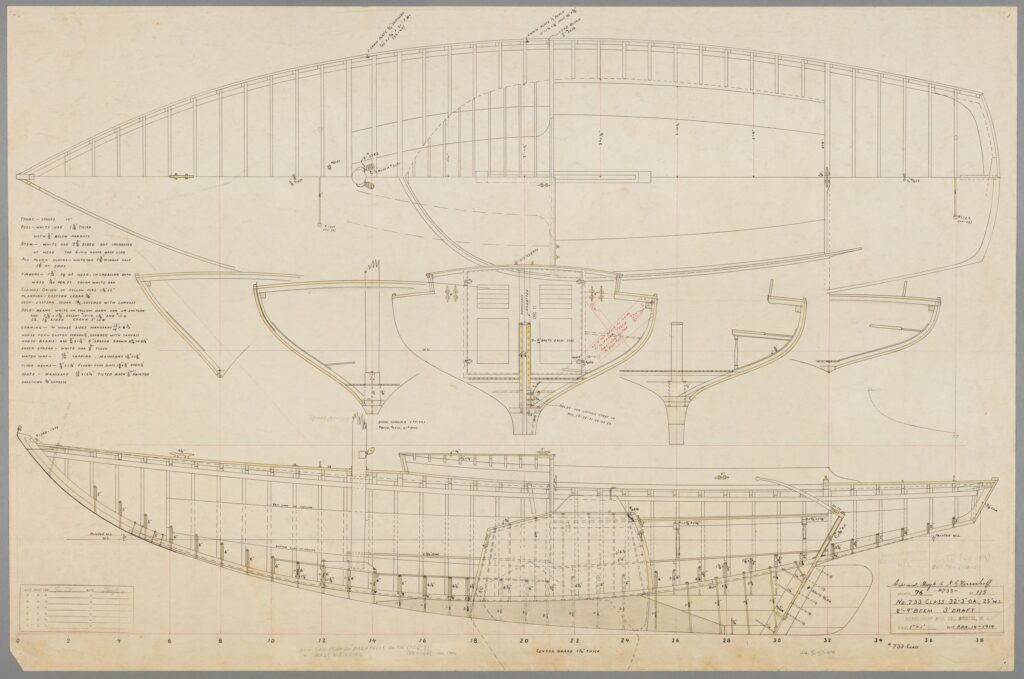

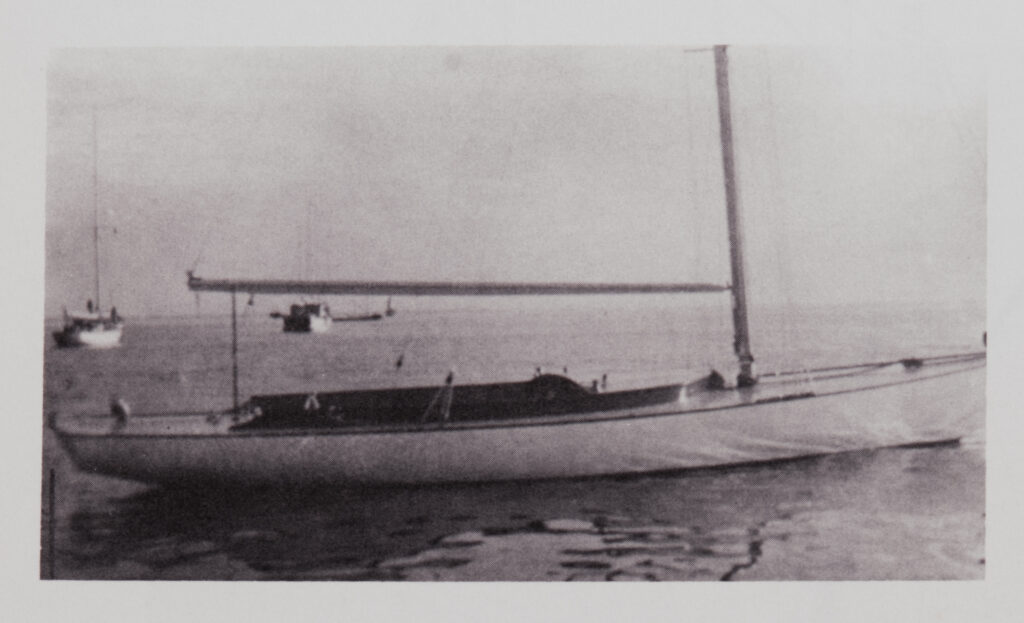

She was designed by Nathanael Greene Herreshoff and built by the Herreshoff Manufacturing Company in 1914 for one C.R. Holmes at a contract price of $2,000.

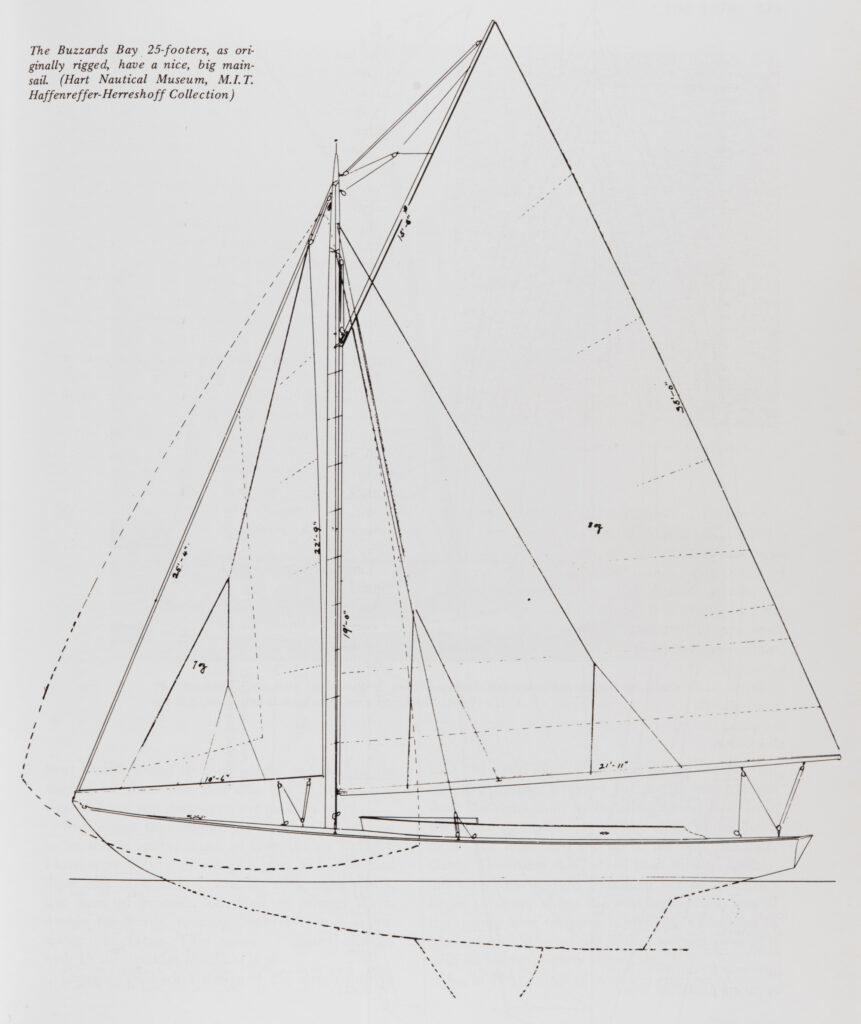

She is Herreshoff hull number 738, and her original name was the Whitecap. She is one of a class of four D Class half-decked sloops designed for racing on Buzzards Bay and generally known as the Buzzards Bay 25-footers, from the length of the waterline. These boats are the Mink, No. 733; Vitessa, No. 734; Bagatelle, No. 736; and the Whitecap. All four were built in 1914. [A fifth, TARANTULA, HMCo. #741, built for stock and sold to W.H. Langshaw in April of 1915, is also considered to be a part of this class by modern historians, though her beam and draft listed in the Construction Record differ very slightly from the BB25 principal dimensions. TARANTULA is the only one of the 5 that no longer survives.]

The boats never became popular as a racing class, and the Herreshoff Company turned out no more of them. They supposedly gained a bad reputation when one of them filled and sank when she was left on her mooring with her mainsail set and sheeted flat and was struck broadside by a squall. They are certainly not tender boats. The only time that the Aria's coaming went under while I had her was when she was struck by a heavy puff just after I had cast off the mooring and, without good steerageway, she was slow to luff.

The Aria is 32 feet 3 inches long on deck, with a waterline length of 25 feet 4 inches, a beam of 8 feet 9 inches, and a draft of 3 feet 1 inch. Her sail area is 490 square feet, and her displacement is just under 4 1/2 tons.

The design is a modification of Captain Nat Herreshoff's third Alerion, hull No. 718, which he designed and built for his own use in 1912 [ALERION III was launched on January 23, 1913]. The Alerion is smaller than the Aria, with a waterline length of 21 feet 9 inches. She has a bit more freeboard and somewhat shorter ends than the Aria, but the basic hull shape is the same. The Alerion is preserved in beautiful condition at the Mystic Seaport. A near sistership to the Alerion is the Sadie, hull No. 732, built in 1914, now also preserved in a museum, that at St. Michaels, Maryland.*

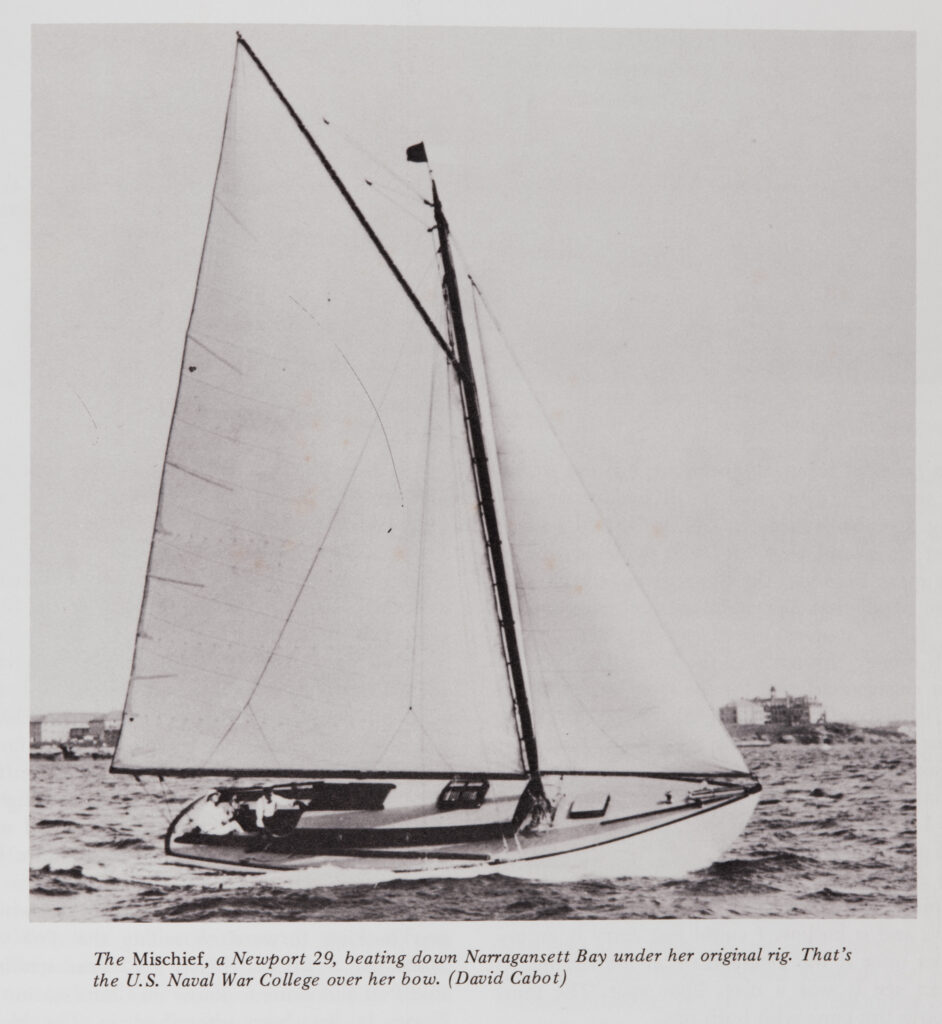

A further modification of this basic design resulted in the Newport 29 class of which three boats were built in 1914: the Dolphin, No. 727; Mischief, No. 728; and Comet, No. 737. These boats have the short ends and high freeboard of the Alerion, and they are keel boats without centerboards. They are 36 feel long on deck, with a waterline length of 29 feet, a beam of 10 feet 4 inches, and a draft of 5 feet.

Seven of these nine boats built by the Herreshoff Manufacturing Company in or before 1914 are going strong, and the other two may be also for all I know.

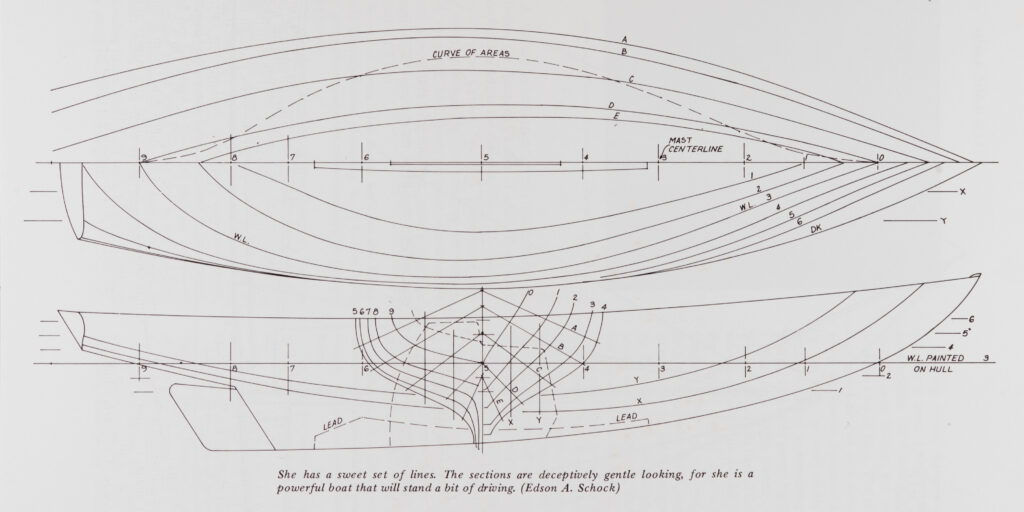

Of the three versions of this design of Captain Nat Herreshoff's, the Alerion, the Buzzards Bay 25-footers, and the Newport 29s, the Buzzards Bay 25s have the finest lines. The Aria was always a sweet and pretty boat to look at and to sail.

Her sections look deceptively easy and gentle, for her bilge is not hard, her draft is quite shoal, and her freeboard is low. Yet she was a powerful boat and could stand driving due to her considerable outside ballast, rather high ballast-to-displacement ratio, great flare in the topsides, and considerable beam. Her broad stem helps her stiffness by giving plenty of bearing aft.

She has about the prettiest bow I have ever seen on a boat. I think the stem profile is the most artistic one Captain Nat ever modeled. The entry is quite hollow, but above the waterline her bow has a lot of flare. The skipper of the only boat that ever beat her in a serious race told me that when the breeze lightened and we began to creep up on him, he was nearly mesmerized by the beauty of that approaching bow with its never-ending, delicately swept back bow wave.

That bow could pound on very rare occasions. When she was well heeled down, one sea in a whole afternoon might be shaped just wrong for her, and she would slap it like a beaver. One time in Gardiner's Bay we ran into a whole succession of such seas and she made such a commotion that I went below to see if she was cracking any frames up forward. The flexibility of her structure under attack was unbelievable. The give was very visible, but she wasn't even weeping.

But that bow loved to cope with 999 out of 1,000 head seas. It would spit ‘em off to leeward and in the process seemed to wedge the boat to weather, so that instead of letting the seas knock her off, she seemed able to use them to shoulder her way to windward.

The bow and buttock lines are shallow for low resistance. She has a very long and flat run for such a small boat.

Her profile gives just the right compromise between steadiness on the helm; it was certainly no work at all In make her go straight - and maneuverability. She could do some fancy stepping and spinning for a 32-footer; we used to wriggle in and out of some narrow waters with glee, and, of course, no engine ever came anywhere near this boat.

The tiller is a small, skinny piece of locust that is beautifully shaped; it looks too small for her, but it isn't.

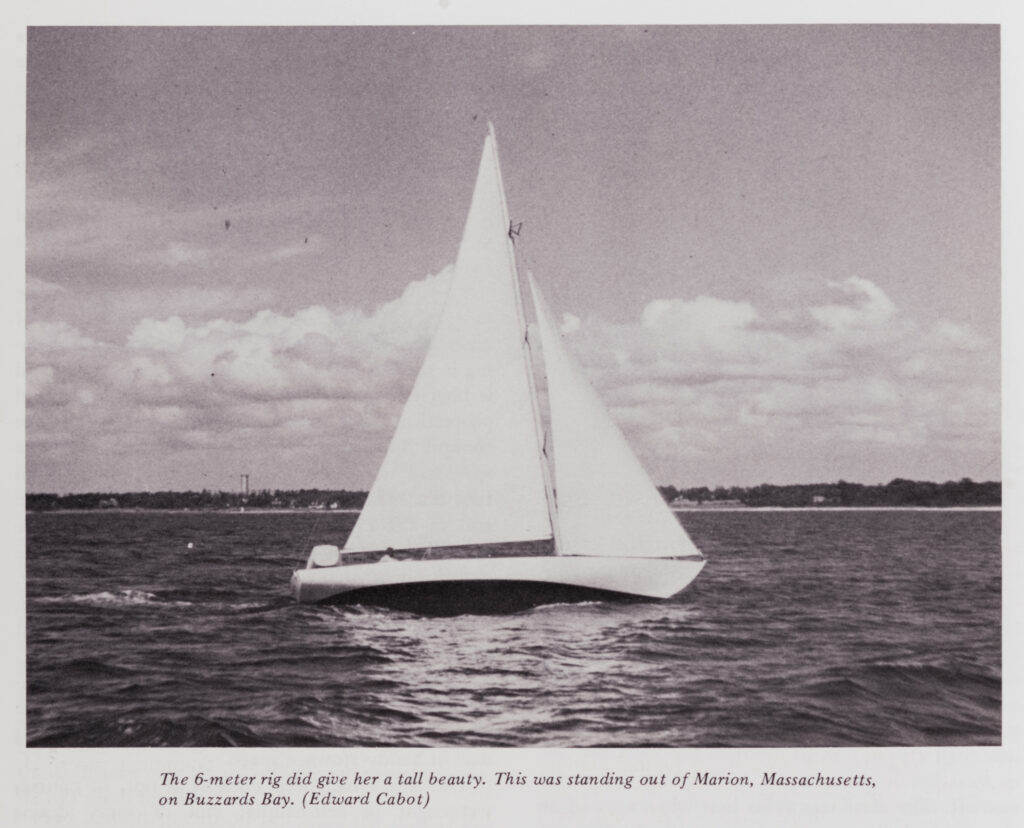

The Aria had a 6-meter rig in her when Pop got her. It suited her well, and the rig conversion had been carried out intelligently.

The mast was 47 feet long from keel to truck. The first time 1 hoisted it out, I simply cast off all the standing rigging, tied it off on the spar, slid the hook on my sheerpole fall a little way above what I thought would be the balance point, and hoisted away. Everything went fine until 1 began lowering the thing down to the horizontal, and then it about bent double under its own weight and that of the rigging. I had no idea that spar was so limber, and figured I had just destroyed the mast. It held.

With a spar that limber, the standing rigging had to be set up pretty tight to keep the rig straight. There were plenty of wires to play with. She had three sets of spreaders, one set of jumper struts, five pairs of shrouds, one pair of jumper stays, double headstays, running backstays, and a permanent backstay. That made 17 pieces of wire with 16 turnbuckles to adjust it all.

Captain Nat hadn't designed the Aria's hull to take the strain imposed by that tall rig with its taut standing rigging. Whoever put the rig into her had done the right thing by installing a steel strap from the sheer clamp in way of the chain plates down under the mast step and up to the opposite sheer clamp. Doubtless this helped hold things together, but after two seasons of sailing her fairly hard, I began to worry about the way the seams in way of the rigging were working. It just didn't seem fair to that delicate, 35-year-old hull to wrench away at it with such a tall, tightly stayed rig.

So, in 1951, another swap was engineered. Sam Jones of Essex, Connecticut, had one of the Aria’s sisters, the Mink, and he still had her original gaff rig. He wasn't using it, and he figured a spare 6-meter rig would be a lot more valuable to him than a spare 1914 gaff rig. So we swapped rigs, and because of all that nice stainless steel wire and all those fancy stainless steel turnbuckles, I got enough money thrown into the bargain so I could buy an engagement ring for the most beautiful girl in the whole world. Slipping that ring on her finger late one night was about the only time I have ever surprised that girl, and putting the original gaff rig back into the Aria was one of the most useful things I have ever done, so Sam, wherever you are, thanks again for the trade.

The gaff rig has about the same sail area as had the 6-meter rig. The mast is 32 feet long, instead of 47 feet, and is hollow. I could just carry it on my shoulder once it was stripped of all the rigging, so you can see it was a nice, light spar. The mast position is the same with both rigs.

The gaff rig has one extra piece of running rigging, the peak halyard, but has only five pieces of standing rigging, a single shroud on each side, a headstay, and a pair of running backstays. So there are five pieces of wire instead of 17 and three turnbuckles instead of 15.

The sails that came with the gaff rig had been made at Herreshoff's, and the mainsail was the most beautifully setting gaff sail I ever saw. There was a club and traveler for the jib, but I had gotten used to the loose-footed jib of the 6-meter rig and so left the club and traveler off and set the new jib loose-footed. When the 6-meter rig had been put in, a nice pair of Luders winches with folding handles had been mounted, one on each after corner of the cuddy roof, and these were so handy I kept them with the gaff rig.

The boat went just as well to windward with the gaff rig as she had with the 6-meter rig. She was never all that close-winded even with the tall, Marconi rig. Deep, narrow boats with tall rigs, like the Eastern Interclubs, could outpoint her with ease, but she had no trouble beating them badly to the windward mark because she footed so fast. The only time she didn't sail as well with the gaff rig as she had with the Marconi rig was in very light airs, when she missed that tall triangle of sail way up high where there is often a little more breeze stirring.

One of the things Pop did during the winter he was looking forward to sailing the Aria was to make her a yuloh. This is a Chinese sculling oar that Pop had come to know on China station in the Navy. It has been described in The Mariner's Catalog, Volume III, and it has been written up and drawn by real experts like George Worcester, so I won't go into it here. Suffice it to say that the yuloh worked just fine on the Aria on those evenings when we had overstayed our welcome in Fisher's Island Sound and were coming up the Pawcatuck River in a flat calm. You could shove her along at a knot or two depending on whether you were lazy or energetic.

The Aria's dinghy has also come in for its share of mention in the Mariner's Catalog. The dinghy' s name was the Ano, by which you can readily sec that it had once been a canoe but had had each end cut off. The Ano was at its best when stowed on the Aria’s deck, across the stern with the Marconi rig, and moved to the foredeck with the gaff rig so it wouldn't foul the mainsheet. If the Ano was light and docile on deck, she was crank and dangerous afloat. One night in Great Salt Pond, Block Island, a guest disregarded my strong suggestion that he not try to row ashore in the Ano against the usual southwest gale. He turned out to be an awfully good man in a small boat, for it took the Ano a full 30 minutes to return him on board, tired, wet, and frustrated through not having come anywhere near his destination.

The ground tackle in the Aria consisted of a 50-pound yachtsman's anchor that had been the Brownie's best bower and a 15-pound yachtsman's anchor that Pop had calculated would be enough to hold her under most circumstances. They were just wrong. The 50-pounder was more than she ever needed; a 35-pounder would have been plenty for a storm anchor. And the 15-pounder always left you worrying a bit; a 25-pounder would have been easy enough to handle and would have given more peace of mind.

The boat has plenty of deck space. There is a lot of room around the mast and her widely flaring bow makes a fine platform for handling headsails. The rather extreme flare to the topsides forward up near the rail makes a fine hand-hold when she' s jumping a bit.

The Aria has a huge, deep cockpit, easily the most comfortable cockpit I have seen in any size of boat. The seats are about 9 1/2 feet long, the coaming is slanted outboard just right for a backrest and is high enough to give you plenty of support and protection. The seats are high enough off the cockpit floor so that you have a really comfortable seat, and when the boat is heeled you have good foot braces in the centerboard trunk at the forward end of the cockpit and the opposite seat at the after end. In this cockpit, you feel as if you are sitting down in the boat, not perched up on her. Six people have plenty of room when sailing, and, of course, you can have quite a party on board at anchor.

Her coaming and seats are made of four beautiful pieces of mahogany. Behind the seats under the deck are long, open shelves that provide a great deal of handy stowage space.

The Aria's big, deep cockpit is not, of course, watertight or self-bailing; rain or spray drains through narrow spaces between the cockpit floorboards directly into the bilge. She has a big tarp that goes over the boom and gaff, the peak halyard and lazy jacks being slacked away to the mast to accommodate it. The tarp covers the entire cockpit and provides a big sheltered area with considerable headroom for a rainy day. It also saves pumping out after a rain and protects considerable acreage of varnish work from the weather. At anchor, you can roll it forward to open up as much of the cockpit as you want to; we often used to set it close-reefed, forming just a nice windbreak over the cuddy and across the forward end of the cockpit.

One thing Pop put in during that last winter was a chart drawer on sail track and slides under the after deck. Sitting at the tiller, all you had to do was reach back through the opening into the lazarette, pull out the drawer, and there were the charts right handy.

No hatch is needed in her cuddy roof, for the cockpit is deep enough so that you can easily stoop and walk into the cabin. Nice louvered mahogany doors can be slid out from under the forward ends of the cockpit seats, slipped onto their pintles, and used to shut off the cabin from the cockpit if desired.

One feature of the boat's construction that Pop said he particularly admired was a pair of strengthening members consisting of fairly wide, straight boards set on edge that ran from each side of the keel up and out to the sheer clamp along the forward face of the bulkhead separating the cuddy from the cockpit. These stiffen her up greatly right amidships without adding much weight to her structure.

In the cuddy there is a narrow seat on each side; there is sitting headroom under the cuddy roof. She has a single pipe berth away forward.

Pop had put in a head at the forward end-of the cabin, but I had little trouble rationalizing its early removal and replacement by a nicely varnished, brass-bound wooden bucket. I also got rid of a water tank way up in the eyes of her and another all the way aft in the lazarette, for I didn't think she needed that kind of weight way out in the ends of her-or that much civilization either, for that matter.

In the after starboard comer of the cabin are some shelves and lockers and a fold-down, single-burner alcohol stove. The centerboard trunk is half in the cabin and half in the cockpit, and the cabin half has a folding table leaf on each side.

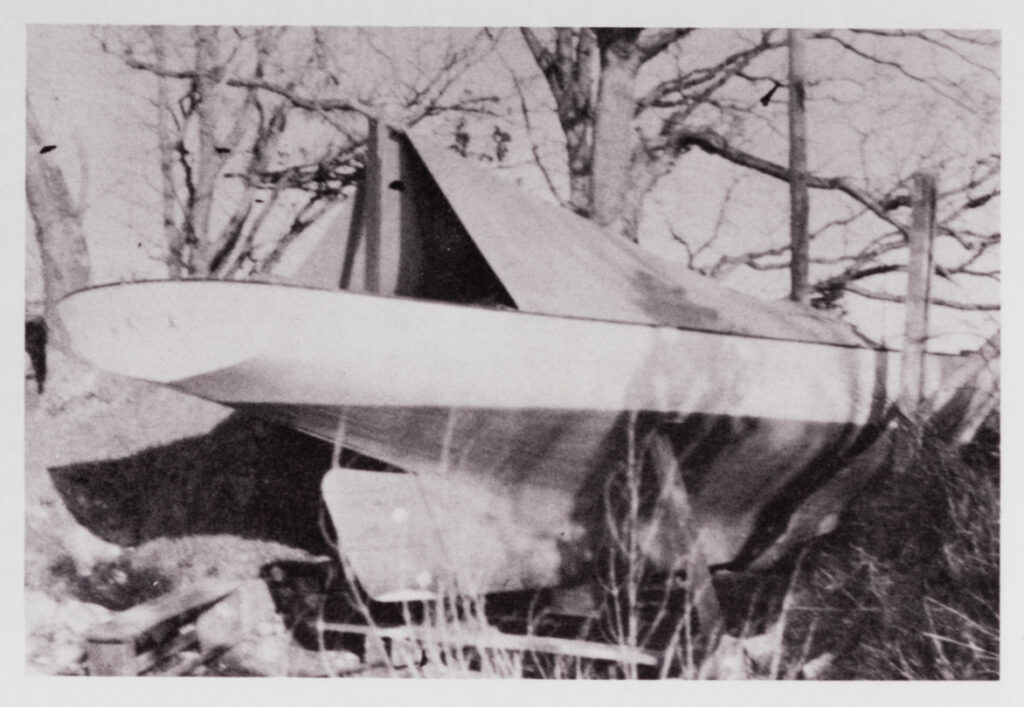

The Aria was hauled and maintained on the railway at Ram Point on the Pawcatuck River that Pop had built for the Brownie. Scraping, sanding. red-leading, puttying, and painting her hull, you got to know her shape pretty well, and every spring's work brought a renewed appreciation for the beauty and soundness of Captain Nat's model.

We'd get most of the work done during spring vacation from school, which meant getting her overboard usually about the third week in April. We'd leave her on the cradle a day or two so the lower seams in the centerboard trunk could swell up-aided by a little sawdust judiciously sprinkled down the slot.

I never made a long cruise in her, but did a lot of day sailing and cruised regularly to the eastward to Buzzards Bay and Vineyard Sound.

My first summer with her I sailed her singlehanded to Buzzards Bay on a ten-day cruise. I made a couple of errors in judgment, both having to do with entering harbors, but the boat was so maneuverable and so well behaved that she got me out of both mistakes unscathed.

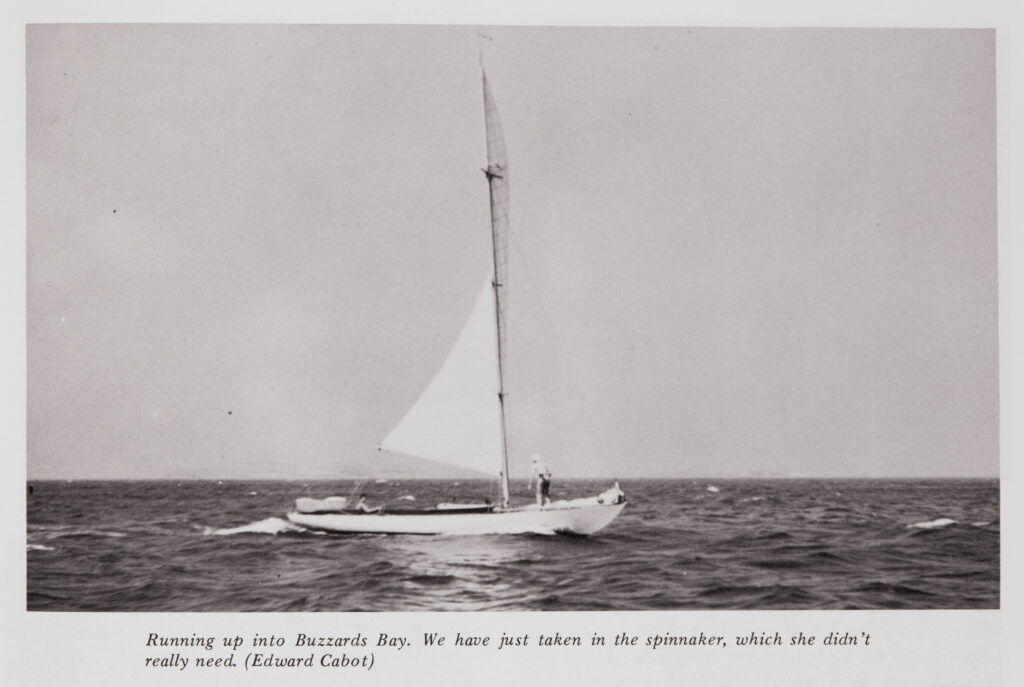

Since the Aria was obviously a fast boat, we wanted to try her out against the competition, so we took her in three Off Soundings races. My regular and best racing crew consisted entirely of Cabots, Ed and Nelson, brothers who had been a major force to contend with in the Herreshoff 15-foot-waterline E class boats on Buzzards Bay and were old enough to remember when the 25-footers came out, and, of course, Ed's son and my very best friend, Dave. These able sailors always took a great interest in the boat and helped me a lot, not just with racing her, but also with her upkeep and general management.

In the three starts in Off Soundings, we took two firsts and a second in Class C, the racing class. The race in which we were beaten was, of course, by far the most interesting. The winning boat was the Flying Scotchman, a new-and at that time novel-light-displacement, fin-keeler, with very high freeboard, reverse sheer, and skimpy sail area. It blew quite hard on both days of the racing, and most of the sailing was to windward. Under these conditions, the Flying Scotchman had things a bit her own way, but we did notice that the one time it moderated, we came right up on her until it breezed on again. The boats would probably be a fairly even match for each other under a wide variety of sailing conditions.

After sailing her for four years, I went into the Navy, and Uncle Sam's operating schedules began to cut down on our sailing time. For part of my first summer in a destroyer, though, the ship was actually in her home port of Newport, Rhode Island, and the recipient of the 6-meter diamond ring and I lived on board the Aria in Brenton’s Cove. Early in the fall came a hurricane scare, and an embarrassed new ensign had to go to the exec to request permission to leave the ship in the face of impending danger. It was my fitness report versus Captain Nat's boat, and I figured there were 300 other guys who could look after that tin can with her 60,000 horsepower. The exec was understanding, and I scooted back home, offered the bride a chance to get ashore dry while she could, and then proceeded to lay out one of the longest scopes of anchor rode ever seen in Newport harbor between Goat Island and Trinity Church. I also tied three reefs into the mainsail, one on top of the other, and generally put away and lashed down everything movable, including the tarp. All we got was much rain, so I spent most of the night pumping.

I guess the Aria’s greatest day while I had her was in a race around Fisher's Island when she beat most of a fleet of far larger boats, including the 72-foot yawl Bolero, boat for boat. Granted, it was a flukey northwest day and we played in under the outside shore of Fisher's Island to the point of hitting the board on a couple of rocks so we could catch what few puffs were coming off the land while the bigger boats had to stay farther offshore becalmed. Still, it was all fair, and 1 have a nice big silver pitcher to help me remember the day.

The Aria didn't get nearly the use she should have had in the next few busy years, and when we moved to Chesapeake Bay, I sold her.

Meanwhile, the Bagetelle, one of the other Buzzards Bay 25s, had been owned first by an uncle and then by Ed Cabot. Ed had rerigged her as a modem yawl. When Ed died, Dave took over his father's boat.

One time I crewed for Dave in the race around Fisher's Island. The Aria was then again owned locally, and she was in the race too. Five of us in the Bagetelle worked very hard on a day with changing conditions, shifting to different-sized Genoa jibs, setting and resetting the mizzen staysail, and fussing with spinnaker and spinnaker staysail. Two fellows in the Aria sailed her around the course with working jib and mainsail, never doing more than trim a sheet now and then. For all our efforts, we in the Bagetelle only beat the Aria by a couple of minutes, and the gaff-rigger saved her time on us. I never could figure out who to root for that day.

Whenever I look back on my experience sailing the Aria, the chief memory that comes up is her surprisingly great speed under all conditions. A couple of years ago I got to worrying that maybe she really hadn't been all that fast and that my remembrance of her fleetness was more nostalgic than accurate. Paul Bates, the Aria’s present owner in Noank, Connecticut, kindly gave me the opportunity to put the worry to the test. We took her out on a nice fresh southwest day, laid her off on a broad reach to Stonington Point, ran up into the harbor and back, and then stood back up Fisher's Island Sound just able to lay Noank, rail down, and going like smoke. It wasn't nostalgia. One more time the boat surprised me with how fast she could sail.

L. Francis Herreshoff once told me that the Buzzards Bay 25-footers were his favorite of his father's designs. That's a mighty powerful statement when you think about it. After ten years of surprises, plus a dividend, I have to agree. I just wish Pop could have sailed the Aria. He really would have loved her.

Paul Bates and Nancy Destang donated ARIA to the Herreshoff Marine Museum in 1993. She is permanently on display in the Hall of Boats at HMM.

*SADIE has also since been donated to HMM, and is on display in the Hall of Boats as well.

Roger Taylor (1932 - 2022) was a lifelong sailor and prolific author and contributor to the world of maritime publishing. His appreciation for all things Herreshoff was broad, from the 15s and his proud ownership of the Buzzards Bay 25 ARIA, now in the collection at HMM, to his definitive two-volume biography of L. Francis Herreshoff. HMM gratefully acknowledges Roger's permission (and encouragement) to reprint a selection of his HMCo.-related essays, granted in the early days of the pandemic.