March 11, 2021

The Herreshoff Brothers and their Torpedo Boats, Part I: The Players, 1860

A series of papers on bringing innovation to the "New Navy"

By Curator Emeritus John J. Palmieri

Introduction

We begin in 1860: a transformative year for the Herreshoff brothers, the U.S. Navy and the individuals who are to play key roles in the Herreshoff torpedo boat story.

(Click the image captions to view larger in a new tab.)

Bristol, 1860

Over the previous twenty years the town had experienced the end of its whaling and sea commerce days and the beginning of its industrial period. In 1837, 19 small whaling vessels called Bristol home and between 1830-1856, 60 vessels were built for both whaling and commerce. This ended when kerosene began to replace whale oil for lighting followed by loss of its foreign trade to the bigger port of Providence. Industrial growth began in the 1830s with the first cotton textile mills, facilitated by the improving transportation infrastructure. Local steamship service between Newport and Providence with stops in Bristol started in 1840. In 1847 the Fall River line expanded service to New York with rail connections to Boston. Rail reached Bristol in 1855 when the Providence, Warren and Bristol rail line opened service on new track connecting Bristol to Providence, Boston and beyond. The 1860 census for Bristol lists a “population” of 5271 plus 234 “colored” people, as was typical of American census records across the nation from the period. [1][2][3]

The Herreshoff Brothers and SPRITE

As young boys John Brown Herreshoff (John) (1841-1915) and Nathanael Greene Herreshoff (Nat) (1848-1938) witnessed these changes. Their original farm home property on Poppasquash Neck included a carpentry shop in what had formerly been living quarters for enslaved people.[4] Their father Charles Frederick Herreshoff (1809-1888), a graduate of Brown, was a gentleman farmer, skilled mechanic, and woodworker who built catboats for himself. Before paved roads, catboats were the pickup trucks of the day, carrying materials throughout the year as well as being vessels for impromptu racing. Charles passed on to the boys the techniques of half model carving, wooden boat building, and how to “properly" sail and care for a boat.[5]

Rather than play, John preferred to visit the local boat builders and machine shops to understand how and why things were done. At age eleven he was making boat models, and then building boats. We are helped by Nat to understand John as a young person and the motivation that drove him to become the aggressive businessman: in the 1930s, at the suggestion of his second wife Ann Roebuck Herreshoff, Nat transcribed his memories in a small notebook which was published by the Herreshoff Marine Museum and 1998 as Recollections. In a piece written, July 23, 1933 titled, “The Old Tannery and My Brother John,” Nat discusses his brother’s life from birth through childhood and early business years in his teens up to the founding of their partnership, the Herreshoff Manufacturing Company (HMCo.) in 1878. John lost sight in one eye due to a cataract at about seven and lost sight from the other at fourteen. Nat notes characteristics in the young John that we see in later life: “strong will and violent temper… a desire to do things other than the usual instruction at school… very quick to learn what interested him… an ambition to earn money.”[6]

In an earlier 1930 letter Nat wrote about John’s loss of sight, his character, and the genesis of the catboat SPRITE. John was “one of indestructible will and energy, who at the age of 14 lost his site, and then had a sailboat of good model and construction almost completed. He also had fitted a very good lathe and had many tools he had bought with money he had earned raising garden crops and in making cotton ropes.[7] The catastrophy only haulted him a few months before his courage came back and in his ‘teens built several small boats and had created a small machine shop. When only 18 - In 1859 he had a desire for a larger and finer sailboat and he with my father to help built SPRITE and she was launched June 28, 1860.”[8]

Following the accident John was taught by his mother, Julia Ann Lewis Herreshoff (1811-1901) to great effect as evidenced by this exchange in a 1900 interview following the Herreshoff America’s Cup wins of 1893, 1895 and 1899, and while work on the 1901 defender was in progress. In that interview, after almost 40 years as a boat builder, he still credited his mother for his ability and success- “I owe her a debt that I can never repay.”[9]

Question: “What do you call the prime requisite of success?”

John’s response- “I shall have to answer that by a somewhat humorous but very shrewd suggestion of an other, --select a good mother.” He continued, to improve the rising generation he would appeal first to mothers, "Above all else show them that reasonable self-denial is a thousandfold better for a boy than to have his every wish gratified. Teach them to encourage industry, economy, concentration of attention and purpose and indomitable persistence.”

Addressing the handicap of blindness as a boy- “It was an obstacle, but I simply would not allow it to discourage me, and did my best, just the same as if I could see. My mother had taught me to think, and so I made thought and memory take the place of eyes. I acquired a habit of mental projection which has allowed me to see models in my mind… and to consider their good and bad points intelligently. Besides, I cultivated my powers of observation to the utmost, in other respects. Even now, I take an occasional trip of observation, for I like to see what others are doing.”

John concluded the interview with the following summary which seems to be a guidepost for his life, formed in the early days of his youth:

“The main thing for a boy is to have a good mother, to heed her advice, to do his best, and not get a ‘swelled head’ as he rises, –in other words not to expect to put a gallon into a pint cup or a bushel into a peck measure. Concentration, decision, industry and economy should be his watchwords, and invincible determination and persistence his rule of action.”

The above provides a clear insight into John’s secret for success. He believed that he could outthink anyone. He refers to "models," but that ability extended to all matters of business. At any time, in any place, on any business occasion he knew he was the most well-prepared man in the room. When engaged in negotiations, he knew he could evaluate matters, see patterns, reach conclusions and form a plan of action before anyone else.

John’s accident and his drive to build SPRITE also changed Nat’s life. In the same October 1930 letter, Nat wrote “when John was 15 and I was 8 I became his companion and spent about all my time out of school with him.” Nat’s childhood was now devoted to the wants of his strong-willed brother. Four years later in 1934 Nat wrote again about the importance of SPRITE to his life’s work: “I was given the first step toward the construction of the boat- that of setting templates over the model where the molds were to be… I thus began my instruction in naval architecture at age of 11½ years.” [10]

Constance Burnett writes that Nat also made a drawing of the spars and sails.[11] This may well be correct because in 1930 Nat provided the Ford Museum a profile drawing of the rigged SPRITE that he wrote was prepared from his memory and notes.

The young Nat learned to become very disciplined and focused on self-improvement, developing extraordinary powers of observation and critical analysis. These were traits that he followed and strengthened throughout his life.

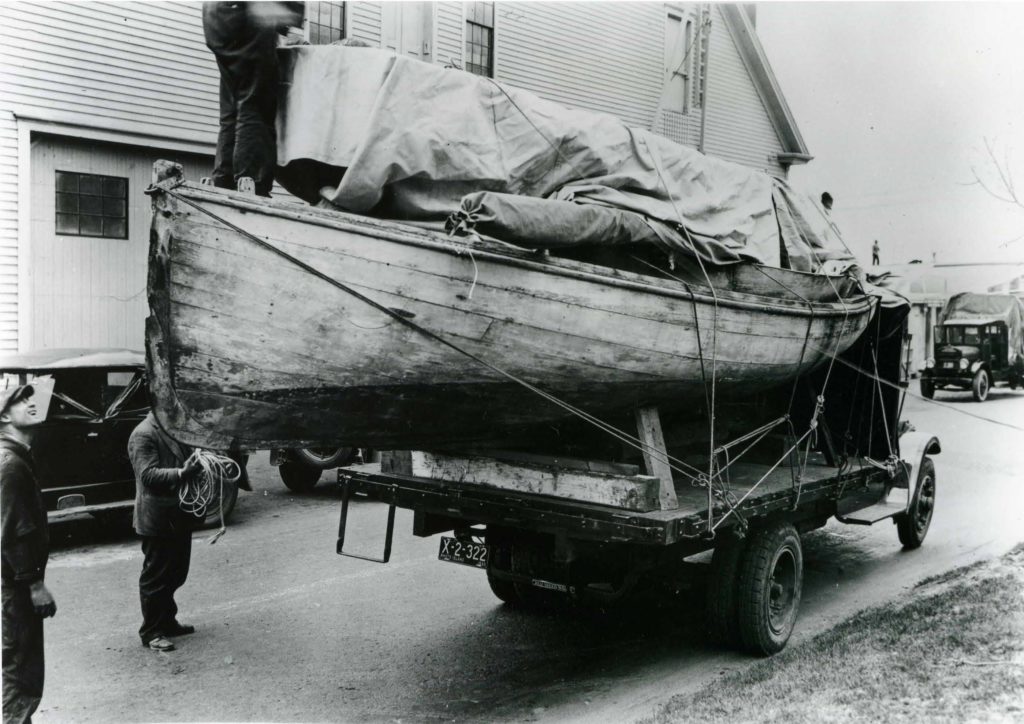

Work on the 20-foot SPRITE started in September 1859. (See SPRITE Figure 1 below.) Assisting the brothers was a local elderly carpenter William Manchester. Working with Manchester, John learned to, “keep a firm leash on his tongue” and to respect the intellect, memory and exacting hands of a skilled craftsman.[12] The launching of SPRITE on June 28, 1860 was timed so that they could sail to New York City to see the steamer GREAT EASTERN that had arrived that very day on its maiden transatlantic voyage.

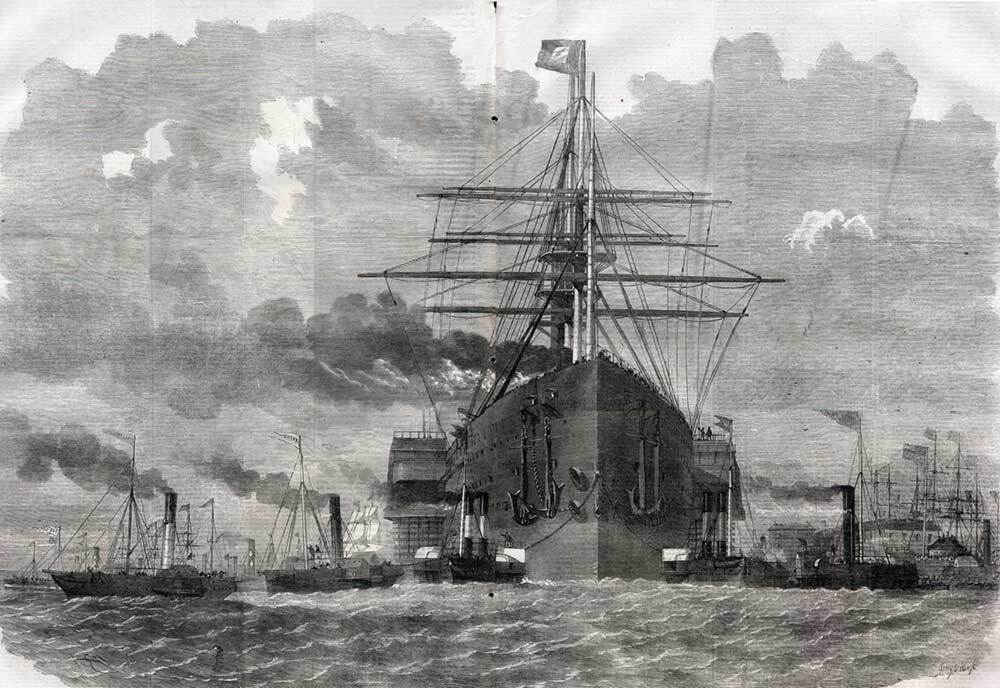

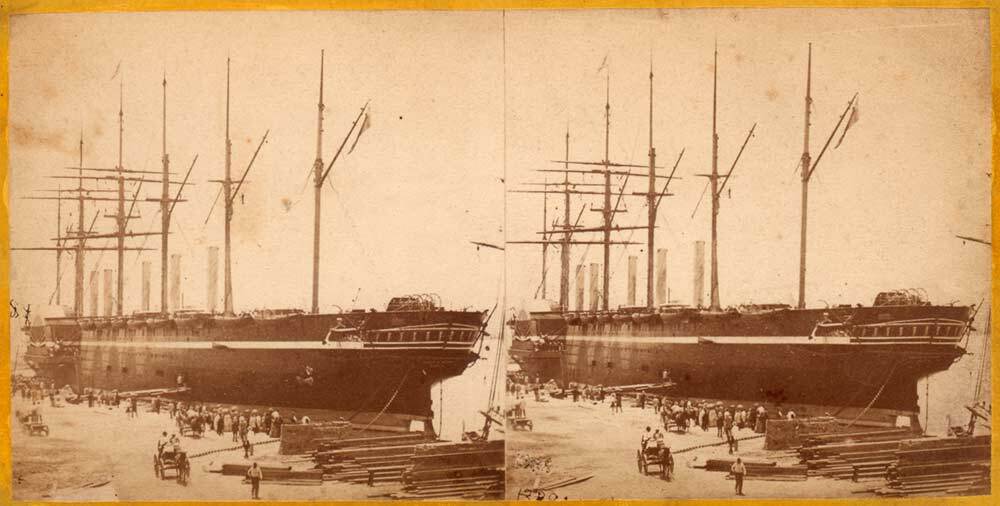

They had first learned of the GREAT EASTERN’s voyage in March and the Bristol Phoenix followed with numerous articles after her arrival. At 680 feet, the largest steamship of its day and the first double-hulled iron ship, the 20,000-ton steamer was the brainchild of Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Powered by 11,000 HP engines driving a screw propeller and sidewheels she achieved 14½ knots. With six masts supporting 6500 square feet of sail GREAT EASTERN was capable of sailing to Australia without the need to refuel enroute. (See GREAT EASTERN Figure 2 below)

Her building and trials had not gone well. The sideways launching took three months to accomplish and drowned her captain in the process. An early trial experienced a funnel explosion and her departure for New York was delayed one day because the crew was drunk. Though a commercial failure as a passenger vessel, the GREAT EASTERN later found success as a cable layer.[13]

At the end of July SPRITE, sailed by John, Nat, and a family friend left Newport accompanied by their father’s JULIA, and arrived off the Brooklyn Navy Yard 28 hours later. On Thursday August 2 SPRITE circled GREAT EASTERN then at anchor off Hoboken, shipboard visiting pier-side having ended three days earlier. What a thrill it must have been for John and Nat to sail over 175 miles in the boat they had built and for Nat to describe to John the latest in steamship technology. It was a significant inspiration to the young boatbuilders as they considered the possibilities of the steam vessels they might build in the future.[14] We know the significance because some 20 years later on a trip to London Nat spent one week’s salary ($30) to buy a four-volume history of GREAT EASTERN. Nat - the frugal Yankee who used every scrap of paper, both front and back - would only spend such a sum for something of great importance to himself. [15]

It was 1860, and the young brothers together had already achieved success. The stage was set for a winning partnership: in less than ten years, they would go on to build their own steam vessels.

Southern Secession Threatens

There was other news that August: in an editorial of the 4th, the Bristol Phoenix was, “really sick of hearing and reading the words disunion and secession. They are the greatest bugbears of the day. In our opinion no sensible man allows such nonsense to enter his brain. There are undoubtedly in some of the Southern States a few mad caps… but thank fortune the number is small.” Meanwhile in the South they were reading of an interview with Governor Letcher of Virginia by a New York Herald reporter. While Letcher personally deplored the idea of a Lincoln victory in November and subsequent secession of some states, he declared empathetically, “while I live, no Federal troops shall march across Virginia against a Southern State.”[16]

The U.S. Navy

The Navy of 1860 was small; 7600 sailors with an appropriation for the Navy proper (less marines and miscellaneous) of just over $10,000,000. The fleet included 26 steam warships, all sail powered with auxiliary engines. Most were on foreign station protecting US commerce. In an attempt to rapidly increase the force, Secretary of the Navy Isaac Toucey (1796-1869) appointed a board to examine the navy’s sailing vessels for conversion into efficient war steamers; they found few candidates. [17] [18]

For decades the Navy had been run directly by the Office of the Secretary supported by a system of boards. This outlived its ability to manage effectively so Congress in the Act of August 31, 1842 established five specialized bureaus under the Secretary to run the business of the Navy. Steam engineering, under an Engineer-in-Chief was included within the new Bureau of Construction Equipment and Repair (BuCE&R). Congress authorized the Secretary to appoint engineers to a Naval Engineer Corps to staff the BuCE&R, as well as operate the shipboard steam plants. Those in the top rank were technically commissioned officers. In practice, they were not “Navy men” but civilian mechanics in officer dress.[19] This introduced new organizational conflict within the Navy. It was a conflict that would later impact the Herreshoff brothers as they introduced their own designs into torpedo boat competition.

The operating squadrons were manned by “Line officers,” literally in line for command at sea. Before steam they did everything. The Constructors, a staff corps, operating now out of BuCE&R designed and constructed the ships; they did not go to sea. Within BuCE&R the new steam engineers were a different breed of staff officer because they went to sea to operate the steam plants they had designed, constructed & maintained. This introduced a long-running conflict with the “Line” over shipboard responsibilities, authority, rank and prerogatives. The other major technical bureau, the Bureau of Ordnance (BuOrd), was free of such problems as it was manned solely by Line officers.

Benjamin Franklin Isherwood (1822-1915)

One member of the board to inspect sailing vessels for conversion to steam was Chief Engineer Benjamin Franklin Isherwood. Isherwood had received his appointment as a first assistant engineer in 1844 on the basis of demonstrating a “working knowledge of marine engines” through experience gained in railroad boiler and engine shops as well as employment at the Novelty Iron Works, a well-known manufacturer of marine engines.[20]

Like Nat Herreshoff, Isherwood started his engineering training at a young age. Before nine he entered Albany Academy a boy’s prep school with a curriculum "more intensive and more thorough than that of many colleges" that "paralleled the course of study at Yale.” Expelled for misconduct in his final year, at age 14 he went to work as a draftsman in a locomotive shop and within two years was considered a "qualified steam engineer".[21]

In February 1848 Isherwood was sent to Europe to study steam engineering and there began his practice of compiling operational and performance data from steam engines and boilers of US and foreign naval and commercial vessels. He used the data to analyze the efficiency of engine designs rather than depending upon the theoretical formulae of the day. Brusque and energetic, Isherwood was withering in his criticism of poor engineering. In 1850, the engines designed by Engineer-in-Chief Haswell (Isherwood’s boss) for the warship SAN JACINTO failed. Risking his recent promotion to Chief Engineer, Isherwood was not deterred in his criticism, describing them as a “disgrace to the service and to our Corps… a standing monument to Mr. Haswell’s incompetency and folly”. Haswell was quickly replaced by Charles B. Stewart, for whom Isherwood had worked in the railroads. The day after Stewart assumed office, he brought Isherwood to Washington DC as his assistant where he supervised machinery design and began contributing compilations of machinery specifications and performance to the scholarly Journal of the Franklin Institute, whose editors were forced to ameliorate the abuse he laid upon his critics. Later in 1858 his experiments to determine the most economical method of using steam in a reciprocating engine solidified him as the Navy‘s best known and most controversial engineer.[22]

David Dixon Porter (1813-1891)

Some thirteen years before, during the Mexican War, Isherwood had served as ship’s engineer aboard the side wheel steamer SPITFIRE under a young lieutenant in his first command assignment, David Dixon Porter. Porter cited Isherwood for his conduct and the excellent performance of the engineering crew. This was a surprising beginning to what would become a contentious relationship between the two. (Figure 3)

In 1860, Porter was the Navy’s most experienced steamship captain, but had stagnated as a Lieutenant for 19 years and was planning to leave the service to take command of a new passenger steamer being built for the Pacific Mail Steamship Company. At sea since the age of ten, Porter had experienced a most unusual career.

His father Commodore David Porter (1780-1843) was a hero of the War of 1812 for destroying the British Pacific whaling fleet. Later (1815-1823) he helped run the Navy as a member of the Board of Naval Commissioners. When Commodore Porter took command of the West Indian Squadron in 1824, his family went to sea with him. In the squadron was the U.S. Navy’s first steamer to serve as a warship, a converted ferry/river steamer, the USS SEA GULL. Young David Dixon thoroughly explored SEA GULL, fascinated by the activities of the engineers while the ship hunted down pirates. In 1825 Commodore Porter was court-martialed for exceeding his authority in an incident ashore. Following a six-month suspension, he abruptly resigned his commission, and assumed command of the Navy of the Republic of Mexico then fighting off Spanish blockades of its ports. David Dixon, age 14, joined the Mexican Navy where as a midshipman he was wounded and imprisoned by the Spanish in Havana. Paroled, he returned to the US and in 1829 entered the naval academy again as a midshipman. [23]

His takeaway from his father’s experience was a general contempt for the Secretary of the Navy and a combination of fear, dislike and respect for politicians, for it was “they” who disgraced his father and denied his mother a widow’s pension. Resolved to restore his father's reputation and pay off his debts while also caring for his mother and a family of his own, Porter often sought assignments that offered extra pay. He served in the Coast Survey for six years prior to the Mexican War because it offered sea pay, traveling expenses and a monthly bonus. Facing Navy reductions following the Mexican war he took a five-year leave of absence (for the pay and modern steam experience) to command Pacific Mail steamers and fast Australian coastal steamers, setting speed records in both services. All were wooden hulled, more than 200’ in length, full-rigged, side wheelers. To make sure the Navy did not forget him he often wrote reports to the Secretary of the Navy about the performance of these steamships. [24]

George Albert Converse (1844 –1909)

In 1860 George was studying in his hometown towards a BS in engineering at Norwich University (The Military College of Vermont). The university had been founded on the principles of a traditional liberal arts curriculum with instruction in engineering and military science. It was intended to provide officers to staff state militias and be a counterbalance to the threat of an aristocratic officer class coming out of West Point. It is unknown whether George Converse had any interest in the Navy at that time.

What Next?

1860 ended quite differently than it had begun. For the very young Herreshoff brothers there was boat building success and a promise for the future. For the Navy there was uncertainty. South Carolina seceded in December and in the officer ranks it was unclear who to trust. David Dixon Porter was at first happy to be leaving it all, but then duty was calling again. What we do know is that 16 years later Porter and Converse would meet in Newport when U.S. Navy Lieutenant Converse took Admiral Porter for a high-speed spin around Coasters Harbor Island in the new Herreshoff-built spar torpedo boat LIGHTNING.

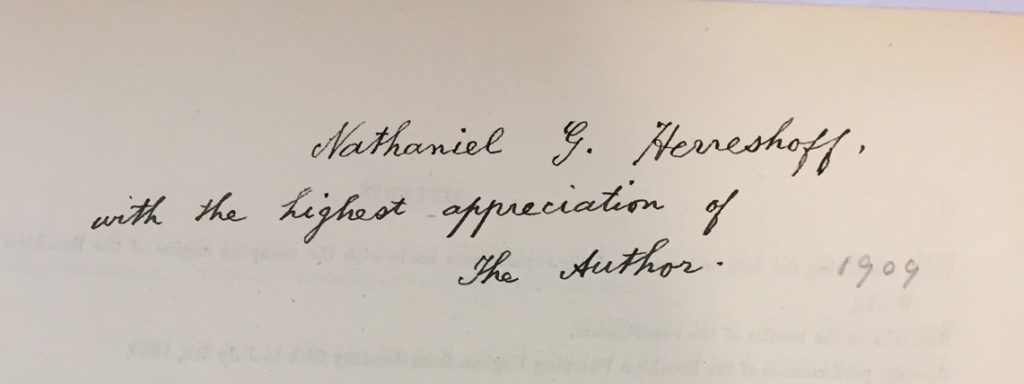

Uncertainty did not extend to Benjamin Isherwood, supremely confident in his analytical approach to solving the steam engineering problems of the day. Though twenty-six years Nat’s senior, we find them in later years to be much alike. In fact, beginning in the 1880s they had personal relationship. For many years Isherwood’s New York City address was the always the first address in the back pages of Nat’s small annual diary, and Isherwood inscribed to Nat a copy of his two-volume 1863-65 book on steam engineering research. (Figure 4).[25]

Source B. F. Isherwood, Experimental Researches in Steam Engineering Vol. 1 & 2. (Phila. W. Hamilton, 1863-65). Nat Herreshoff personal library, Herreshoff Marine Museum Model Workshop Bookcase. Isherwood letter to Nat June 29, 1909, N.G. Herreshoff Collection. Herreshoff Marine Museum. Access courtesy Halsey C. Herreshoff.

Both were to achieve great success in careers built upon continuing self-improvement, careful study, analyses, observation and test. Neither suffered critics; Isherwood by heaping abuse upon them and Nat Herreshoff by simply keeping his peace and ignoring their never-ending dribble.

The next paper will explore the Civil War and its aftermath.

[1] Historical and Architectural Resources of Bristol RI. Rhode Island Historical Preservation Commission, 1990 Pages 18-19.

[2] Robert A. Geake, A History of the Providence River with the Moshassuck, Woonasquatucket & Seekonk Rivers. (Charleston, SC, The History Press 2013)

[3] Carl D. Lane, American Paddle Steamboats. (New York, Coward McCann Inc. 1943) Pgs. 18-20.

[4] Constance Buel Burnett, Let the Best Boat Win. Cambridge, MA, The Riverside Press, 1957). Pg. 16. (This book is written in a quoted narrative style as “if we were there”. There are no footnotes, but sources include Family members (L. Francis, Sydney & Agnes Herreshoff), fellow NYYC members, and Rudder articles by L. Francis Herreshoff.)

[5] “Properly” as practiced on their father’s catboats meant- small boats never touched the topsides; before boarding check shoes and boots for protruding nails or any blacking that would rub on the boat, then sponge the soles clean; sails clean and white –only washed hands used in furling; each full and new moon boat laid ashore and bottom scrubbed. Source, Carlton J. Pinheiro Editor, Recollections and Other Writings by Nathanael G. Herreshoff. Bristol RI: Herreshoff Marine Museum, 1998 Pg. 12.

[6] Pinheiro. Recollections. Pg. 5.

[7] One of his crops was onions. At the time there was a large export market shipping Bristol onions to Cuba.

[8] “Nat Herreshoff letter Oct. 9, 1930 to J. H. Humberstone, Edison Institute of Technology, Dearborn, MI.”, SPRITE Transfer Folder Curator Archives Herreshoff Marine Museum. (Written when SPRITE was transferred to Dearborn for restoration at Henry Ford’s request.)

[9]Orison Swett Marden. How They Succeeded: Life Stories of Successful Men Told by Themselves. (Boston: Lothrop Publishing Co., 1901) “Chapter XVII John B. Herreshoff, The Yacht Builder”. Pages 280-1; 287-8. (Other business leaders featured include Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller, further evidence of John’s stature in American business.)

[10] Pinheiro, Recollections, Pg. 40.

[11] Burnett, Let the Best Boat Win. Pg. 72.

[12] Ibid., Pg. 72.

[13] www.atlantic-cable.com/Cableships/GreatEastern/

[14] Pinheiro, Recollections, Pg 12-13.

[15] Vincent W. Gilpin, Extracts of Letters from Commodore Ralph M. Munroe of Coconut Grove FL, 1903-1933. Letter of Feb. 24, 1929recounts Nat Herreshoff purchase of a complete history of GREAT EASTERN for “somewhere about one week salary”. Herreshoff Marine Museum archives. $30/week salary is taken from 1881 data in spreadsheet compiling “NGH Diaries & Cash Account Records 1881- 1915: Plus, selected comments from May 1918. Rev 2. Feb. 12,2014. JJ Palmieri, Curator”. Herreshoff Marine Museum Curator Files.

[16] The Anderson Intelligence, Anderson, SC. Aug. 21, 1860.

[17] “The Navy Department; Report of Hon. Isaac Toucey, Secretary of the Navy” New York Times, Dec. 5, 1860.

[18] Secretary of the Navy Annual Report Dec. 1, 1861. (GPO; Wash DC 1861)Pg. 13. (Secretary of the Navy Annual Reports are available online at hathitrust.org)

[19] Edward William Sloan, III. Benjamin Franklin Isherwood Naval Engineer: The Years as Engineer in Chief 1861- 1869. (Annapolis MD: USNI, 1965). Pgs. 3-4 & 9-10.

[20] Ibid, Pgs. 9-10.

[21] Ibid, Pgs. 6-7.

[22] Ibid, Pgs. 13-14, 17, 81. He contributed over 100 articles to the Journal during his career

[23] Information on Commodore David Porter & David Dixon Porter early years taken from Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937). Pgs. 12-17. Tamara Moser Melia. “David Dixon Porter: Fighting Sailor” from James C. Bradford, Editor, Captains of the Old Steam Navy: Makers of the American Naval Tradition 1840-1880. (Annapolis, MD; Naval Institute Press 1986). Pgs. 227-228.Part of the Makers of the American Naval Tradition Series. “Biographical Notes” David D Porter Family Papers. Manuscript Division,Library of Congress, Revised April 2010. Pgs. 3-5.

[24] West, The Second Admiral. Pgs. 16-17, 34, 38-9, 51-9.

[25] In addition to Isherwood’s business trips to the HMCo to conduct Navy trials of their latest steam vessels, Nat Herreshoff’s diaries record at least one social visit by Isherwood to Bristol. We have found no correspondence between the two, other than the inscription, Figure 4. This is an area for additional research.