May 14, 2020

Curator’s Log: Bristol, HMCo., and the Pandemic of 1918

How the movement of military personnel, the crowding of factories for war-time production, rallies, parades and the Liberty Bond Campaign impacted HMCo. and Bristol in the influenza pandemic more than a hundred years ago

by John Palmieri

Introduction

The advent of the European war in 1914 forced change upon American towns and businesses. Initially much of the commerce with Europe was disrupted. As risk of American involvement increased, government actions to implement selective service and equip an expanding military created shortages and strained the overall economy.

Then in 1918 the pandemic of influenza (“Spanish Flu”) struck, quickly overwhelming a medical system already short of doctors and nurses mobilized for military service. Half-a-million Americans died; 100,000 short of the population of Rhode Island at the time. Believed to have been born in the spring of 1918 in the military camps in Kansas, it spread worldwide, and by summer and autumn of 1918 it reached New England aided by the conditions existent at that time:

- - The constant movement of military personnel across the US; to and from Europe.

- - The crowding of workers into industrial plants as required for war production.

- - From September 28 through October 19 meetings, rallies and parades associated with the 4th Liberty Bond campaign brought large numbers of people together at the very worst time in the life of the pandemic.

- - Before radio, TV and the myriad means of communication we enjoy today, public entertainment in dance halls, saloons and theatres brought uninfected together with others “who were shedding the virus.”[1]

This paper explores how these factors affected the town of Bristol and the Herreshoff Manufacturing Co. (HMCo.)

War Brings Change and Shortages to Bristol; Great Challenge to Herreshoff

Bristol had been an industrial town since the Civil War with railway connection to Boston and steamship lines to New York, Providence, Fall River and Newport. Its industry included textile mills on Thames Street, the HMCo. on Hope Street and the National India Rubber Company (later US Rubber), the town’s largest employer, on a large 19-acre Wood Street site. [2]

With war the town’s population increased about 20% to 11,000, employment was up at the textile mills and National Rubber doubled from 2000 to 4000 employees. Beginning in 1916 a local board implemented the Selective Service draft of young men into the army. There were shortages. In 1917 Capt. Nat Herreshoff offered a portion of his farm off Griswold Ave. to HMCo. employees to grow their own food. In the winter 1917-18 fuel shortages caused schools, saloons, and factories not doing government work to periodically close; for example, a 10-week “fuel saving Monday” in January and February 1918.[3] Following the US entry into the war in April 1917, suspected German spies were even arrested for “suspicious actions” near the Herreshoff plant.[4]

At Herreshoff, although the order book was full in 1914 and remained so through 1916 with a workforce topping at a “full-employment” level of 500, the company was about to face its greatest challenges since John and Nat formed their partnership in 1879.

In the summer 1914 HMCo. was completing tune up of RESOLUTE (HMCo. #725), their latest America’s Cup defender, when the August start of hostilities cancelled the race. Just as well, because Capt. Nat was in poor health and after a hospital stay in November he convalesced through the winter in Bermuda. During that time John negotiated a contract, and accepted advance payment from the Russian government, for 60-foot high-speed sub-chasers. He saw the contract as guaranteeing HMCo. a lead position in the large number of sub-chaser and torpedo boat contracts sure to follow from US and allied nations. But in April 1915, on return from Bermuda, Nat rejected the contract on the basis that the performance guarantees agreed to by John could not be met. John passed away shortly thereafter on July 20th at age 74. [5] Nat recorded in his diary, "My brother John died last night at 2:30 quite unexpected of angina-pectoris.”[6]

Capt. Nat continued on alone, filling orders for the very successful H-12½s, and the newly designed Fish Class, NY 40s and assorted power vessels. But as he wrote in 1934:

“Not having or caring for business ability and not finding anyone that appeared fit and capable to take John’s place to manage the business end of the company, I reluctantly consented to sell the (HMCo), and 1917 saw the end of what had been a wonderfully successful enterprise in small craft construction.”[7]

In February 1917 HMCo. was re-formed by a syndicate of New York and Boston yachtsmen into a stock company; Capt. Nat, president and designer; a shipyard experienced business manager, James Swan; and to attract more US Navy business, Boston naval architect/designer A. Loring Swasey. The people of Bristol and the Bristol Phoenix looked forward to success of the enterprise and “probable enlargement of the plant.”[8]

In just under two months, the US declared war and all yacht construction ceased.

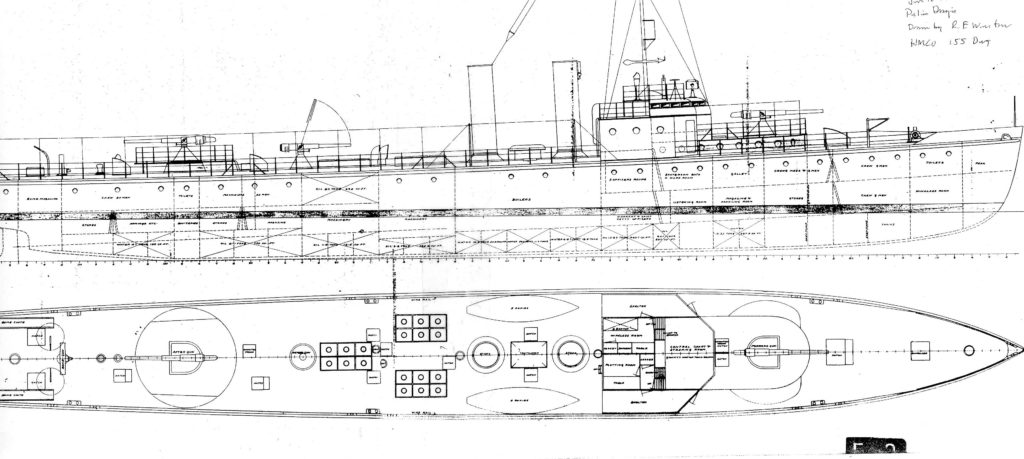

HMCo. won a hodge-podge of wartime orders. Beginning in 1916, at the instigation of Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt, wealthy yachtsmen ordered patrol boats, varying in sizes from 55-110 foot waterline length for donation to the Navy. (See Figure 1, New York Times April 1, 1917 “Yachtsmen Order Submarine Chasers”.) There followed 40-foot torpedo retrievers, seaplane barges and pontoons, and flying boat hulls; but none could maintain the employment levels and constant steel and mechanical work offered by what HMCo. really wanted to build: 200-foot sub-chasers (See Figure 2: Preliminary Design 200-foot Chaser).[9]

Fig. 2: detail of preliminary design for 200-foot Chaser, courtesy the Haffenreffer-Herresoff Collection at the MIT Museum.

A frustrated Capt. Nat saw the delays and impediments to Navy approval of the design (an approval that never came) as a repeat of the, “jealous feeling the Navy Dept. has always had against anything originated here.”[10]

By the time the influenza hit in late summer 1918 HMCo. employment was down to 280.

Pandemic - September 1918 Influenza Reaches Rhode Island

The virus spread in several waves to US military camps across the US. It moved rapidly before any travel bans could be imposed and quickly infected neighboring communities. The rapid spread was aided by two factors: the disease was contagious before symptoms were recognized, and incubation rarely exceeded three days. In August, Camp Devens (MA) became a hot spot, on August 28th the Naval Hospital Chelsea, MA had its first case and by early September flu had reached a naval facility, the Rumford Rifle Range, across the river from Brown University and then Naval Training Station Newport, where by mid-September there were over 700 cases with more at Fort Adams. Rhode Island had an especially severe shortage of nurses as a large number had volunteered for national duty during the early stages of the pandemic; student nurses took their place. Emergency hospitals were set up in Pawtucket, Woonsocket, Warwick and Westerly. Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels established an official policy directing navy medical staff to offer “No Assistance to Civilians”. Fortunately, it was ignored at all levels and the navy locally staffed emergency hospitals in Newport, Jamestown and Little Compton. By early November the state was reporting (within the civilian population) 50 deaths per day; the total count: at minimum 2500 victims in 1918. [11]

On September 27 the Rhode Island State Board of Health recommended that the governor order all places a public amusement closed. The recommendation was opposed by the mayor of Providence and the city’s superintendent of health, Doctor Charles V. Chapin. Chapin, respected and influential in the state, thought that it was too late for such an order to be effective, and the epidemic should be allowed to run its course. The governor did not issue the closure order.[12]

Concerned by the lack of state action, and with local cases of influenza and associated pneumonia increasing, Bristol Health Officer Dr. Henry L. Teller ordered schools and motion picture theaters closed as of September 30th until “spread of the disease is checked”; they remained closed for three weeks. By October 4th there were at least 300 cases in Bristol, including 10 of 16 children at the Childrens Home. In the next week the count increased another 100, although seemingly not particularly virulent, Teller considered it a “grave menace to the well-being of the town”. Clergy were asked to omit services and close their churches; all taverns and pool halls were closed. Rodgers Library stopped giving out books. Absenteeism was high at all factories including Herreshoff, but only National Rubber found it necessary to close for several days. They all continued with no apparent organized and planned effort to reduce employee exposure.

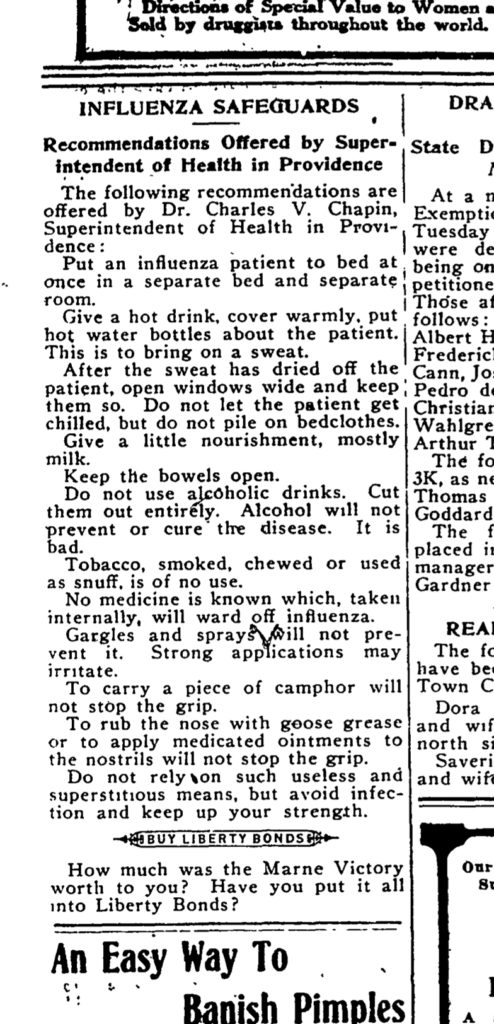

The bi-weekly Bristol Phoenix carried an “Influenza Situation” column about the disease and tracked numbers of new cases. One page was devoted to obituaries; there were 13 in the October 15 issue. The Phoenix joined other state newspapers in publishing a list of “Influenza Safeguards” prepared by Dr. Chapin. (See Figure 3 “Influenza Safeguards” Bristol Phoenix, Oct. 11, 1918.) The article is interesting because it provides insight into the state of treatment at the time and the kinds of mythical cures that were alive in public discourse. There were also charlatans offering relief. One recurring ad for Hill’s Cascara Quinine Bromide under the banner, “Spanish Influenza can be prevented easier than it can be cured”, promised “To kill it quick.”[13]

By mid-October the epidemic was beginning to wane as judged by the decreasing number of new cases. Between October 18 & 23 the Town Council lifted all bans and reopened the schools. But the influenza was still in the community; school attendance was at only 50% and did not recover to 90% until January.[14]

Bristol’s 4th Liberty Bond Campaign- Sept. 28- Oct. 19, 1918

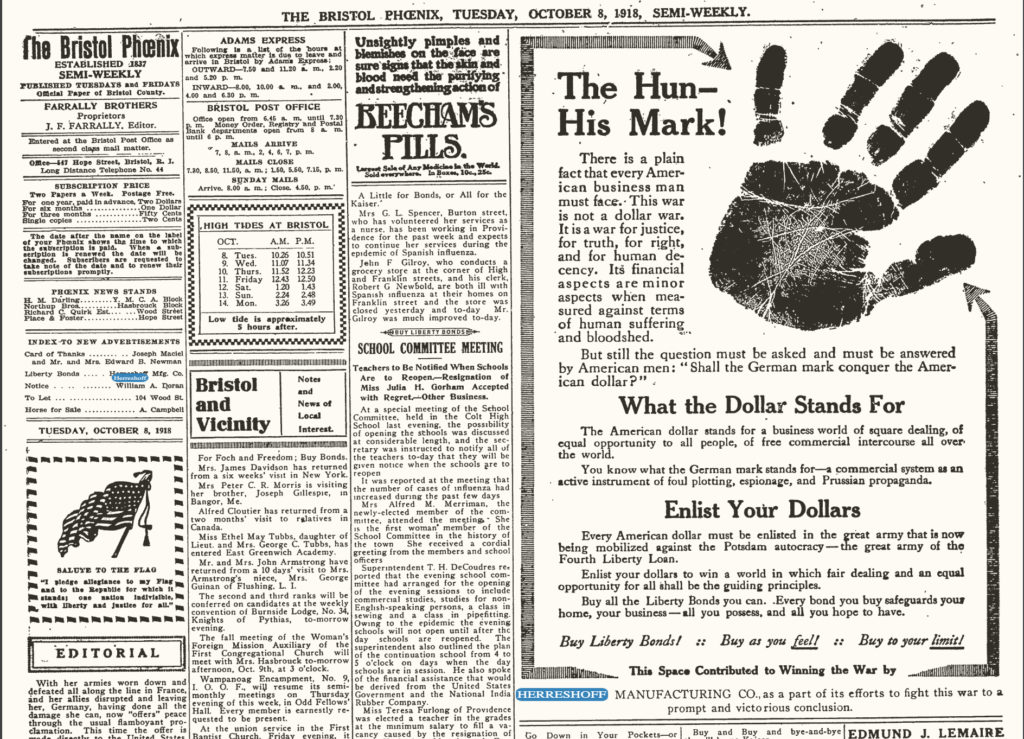

The nominal kickoff of the campaign was a handwritten letter from President Woodrow Wilson, published on October 1st in all newspapers exhorting the purchase of the bonds so that the American people will “show the world for what their wealth was intended.” Under the banner “The Fighting Fourth Loan” Bristolians learned their quota was $400,000 (out of the state’s $50M); and nearly twice that of the 3rd campaign.[15] There followed a flurry of organization & publicity to secure the amount. By October 2nd $150,000 had been raised. Local committees held many events and rallies. There were joint meetings of foremen & foreladies of National India Rubber with foremen of HMCo. and Cranston Worsted Mills to plan campaign events, displays, sales and encourage a rivalry between companies for the highest percentage employee participation and most dollars raised per participant. Rotating ads in the Phoenix financed by the three companies kept up the drumbeat.[16] (Figure 5 Bristol Phoenix Oct. 8, 1918 HMCo. Ad for the 4th Bond campaign.)

When completed HMCo. won with 95% participation, and National India Rubber with $73/employee. Bristol exceeded its quota by 50% and had 40-50% citizen participation.[17] All very well and good except that it aided the spread of the pandemic by bringing/forcing groups together during the worst days. In normal times there would have been little social contact between the English / Scottish steel workers of HMCo., the Irish in the mills, and the Portuguese / Italians at National Rubber.

Bristol was not alone. In Newport, thousands of sailors from the Naval Training Station were allowed to march through the town in a Liberty Loan Day parade even though hundreds of other trainees were already quarantined with influenza.[18]

Aftermath

Influenza did not just go away. There was a resurgence in December and January, though the cases were less serious. Newport schools were especially hard hit and closed for an extra week at Christmas; absences in Bristol remained high. In late December, to keep better track of another potential epidemic, the State Board of Health added influenza to the mandatory list of reportable diseases. A year later, January 1920, found Bristol physicians and nurses overworked treating “hundreds of cases of colds and 125 cases of influenza”. The milder nature of the cases suggested some immunity had been established.[19] Later that spring as the HMCo. again readied the America’s Cup contender RESOLUTE for a challenger series with VANITIE, Captain Nat was noticeably absent, unable to go because he was “recovering from a severe attack of influenza”.[20]

John. J. Palmieri

[1] Capt. Thomas L. Snyder, MC, USN (Ret), “Navy Support of Civilian Authorities During the 1918 Influenza Pandemic- History’s Lessons and Recommendations for Future Work.” Military Medicine, Vol. 174. November 2009. Pg. 1223

[2] “HISTORICAL AND ARCHITECTURAL RESOURCES OF BRISTOL, RI” Rhode Island Historical Preservation Commission 1990. Pages 19-20.

[3] The Bristol Phoenix, May 1, 1917; Jan. 22, 1918.

[4] The Bristol Phoenix, July 20, 1917 and “The HMCo Watchmen” Curator’s Log May 2015. https://herreshoff.org/2015/05/the-curators-log-may-2015/. A second suspect was arrested a few days later; Bristol Phoenix, July 24, 1917.

[5] “This Month in Herreshoff History- July 1915”. https://herreshoff.org/2019/07/this-month-in-herreshoff-history-july-1915-2/

[6] Nathanael G. Herreshoff diary entry July 20, 1915. Herreshoff Collection, Herreshoff Marine Museum. Access courtesy Halsey C. Herreshoff.

[7] Nathanael G. Herreshoff, “Some of the Boats I Have Sailed In” Recollections, Edited by C. J. Pinheiro, Herreshoff Marine Museum, 1998, pg. 73

[8] “Herreshoffs Re-Organized”. Bristol Phoenix, Feb. 11, 1917.

[9] “HMCo Untitled Drawing; Folder 155 Preliminary Design; June 1918; drawn by R. E. Winston” Haffenreffer- Herreshoff Collection. MIT Museum.

[10] Nat Herreshoff Letter to George Cormack, Secretary New York Yacht Club of June 1, 1918. Herreshoff Collection. Herreshoff Marine Museum. Access courtesy Halsey C. Herreshoff.

[11] Compiled from following sources

Snyder, page 1224

“Influenza and Quarantine; Brown in the Great War.” Brown University Library

“The US Military and the Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919” Public Health Report 2010; 125 (Suppl 3): 82–91.

“Providence, Rhode Island and the Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919” Influenza Encyclopedia. Univ. of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing. Univ. Michigan Library.

“Rhode Island: The Great Pandemic of 1918: State by State”. Opening remarks prepared for delivery by

Mike Leavitt Secretary of HHS. Jan. 13, 2006.

The Bristol Phoenix July 23, 1918, reprint from London Chronicle, “Rapid Spread of Influenza”.

The Bristol Phoenix, Sept. 17, 1918, Cases at Newport Training Station.

[12] “Providence, Rhode Island and the Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919” Influenza Encyclopedia.

[13] The Bristol Phoenix, “Influenza Cases Increasing” Oct. 11 & 15, 1918. The Quinine Bromide ad Nov. 12, 1918.

[14] The Bristol Phoenix, “Influenza Waning” Oct. 18, 1918. Oct. 22, 29, 1918. Nov. 8, 1918. Jan. 21, 1919.

[15] The Bristol Phoenix, “The Fighting Fourth Loan” Oct. 1, 1918.

[16] The Bristol Phoenix, Oct. 4, 1918

[17] The Bristol Phoenix, Oct. 8, 11, 15, 1918

[18] Newport Mercury, Oct. 19, 1918

[19] Newport Mercury, Dec. 21, 1918. “Providence, Rhode Island and the Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919” Influenza Encyclopedia. The Bristol Phoenix, Aug. 8, 1919, Jan. 30, 1920.

[20] The Bristol Phoenix, May 21, 1920.