May 25, 2021

Nathanael Greene Herreshoff: Steam Engineer, The Corliss Years

Guest post written by Jim Giblin

NGH: Steam Engineer, The Corliss Years

by Jim Giblin

“I believe N. G. throughout his life remained at heart a steam engineer.

I believe his happiest moments were when he was designing steam engines with their complicated mathematics.”

- L. Francis Herreshoff 1944. [1]

[1] Nathanael's Greene Herreshoff 1848-1938 Wadsworth Atheneum Marine Room, Publication Number 2, Pg. 15.

The MIT Museum Exhibit “Lighter, Stronger, Faster; The Herreshoff Legacy” credits Nathanael with more than fifty separate steam engine designs.[2]

[2] MIT Museum Exhibit “Lighter, Stronger, Faster; The Herreshoff Legacy,” 2018-2019.

Introduction

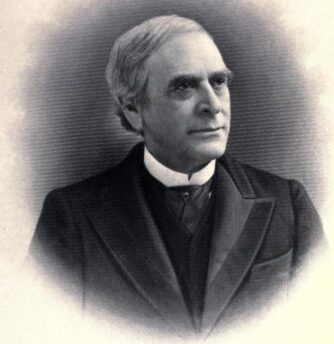

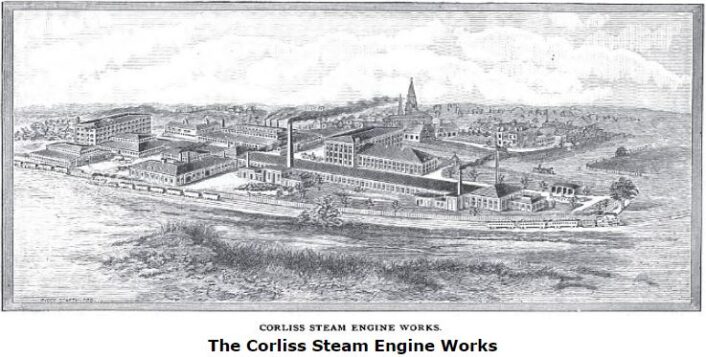

In 1848, the same year Nathanael was born, George Corliss (age 31) and E.J. Nightingale formed the Corliss Nightingale Company. The first steam engine incorporating George Corliss revolutionary steam inlet and exhaust valve control linkage and its associated valve design was produced the same year. This development dramatically improved the efficiency of an engine and set the stage for a new era of steam engines. The corresponding patent was issued in 1849.[5] In 1856 George Corliss bought out his partners and the company became the Corliss Steam Engine Company. By the time Nathanael joined the company in 1869 there were over 1,200 Corliss engines totaling 118,500 HP in service.[6] The Corliss plant covered five acres on Charles Street and at times employed nearly 1,000 people.[5] The Corliss Company's principal product was the horizontal stationary steam engine used in the manufacturing industries. Corliss did build a few large water pumping engines and a small number of his engines were used in marine applications. The Corliss engines were particularly valued - both here and in Europe - by the textile and steel rolling mills, not just for their fuel economy and quality of construction but also for their ability to automatically maintain a constant speed under varying loads. These characteristics improved both the quality and quantity of products of both these industries and others. The dramatically improved efficiency imparted by the Corliss patents transformed manufacturing as it permitted steam power to become both more economical and more reliable than waterpower. This in turn fostered industrial development in urban centers which possessed superior access to both transportation and labor.[7]

[5] Rhode Island History Magazine, January 1946, Pg. 5,6,7,8.

[5] Rhode Island History Magazine, January 1946, Pg. 5,6,7,8.

[6] A general Purpose Technology At Work, The Corliss Steam Engine In The late 19th Century, Nathan Rosenberg, Pg.14.

[7] A general Purpose Technology At Work, The Corliss Steam Engine In The late 19th Century, Nathan Rosenberg. Pg 10,11.

A Draughtsman’s Position

Upon his completion of studies at MIT in 1869 Nathanael became a member of a select group of individuals who had formally studied mechanical engineering and the thermodynamics of steam. The MIT graduation records indicate that between 1868 and 1870 only five of the 29 MIT graduates were mechanical engineers.[8] At the time most designers of mechanical equipment were, like George Corliss and Edwin Reynolds, intelligent, very inventive, mechanically inclined individuals whose designs were empirically developed based upon the knowledge and skills acquired by observation and in the shops. In his Annual Report of 1895, the President of MIT had this to say regarding early mechanical engineers: “But few, even of intelligent and cultivated people in 1865 knew what a mechanical engineer was, why he should be called so, or what problems he would be called upon to attack. It was not until young men began to go out from this and other schools trained as mechanical engineers that manufactures, bridge builders, railroad corporations, and persons in a hundred industries who were charged with the generation of power found out that they wanted just such men.”[9]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[8] MIT Presidents Annual Report 1895 MIT Archives.org, Pg 22.

[9] MIT Presidents Annual Report 1895 MIT Archives.org, Pg. 8-9.

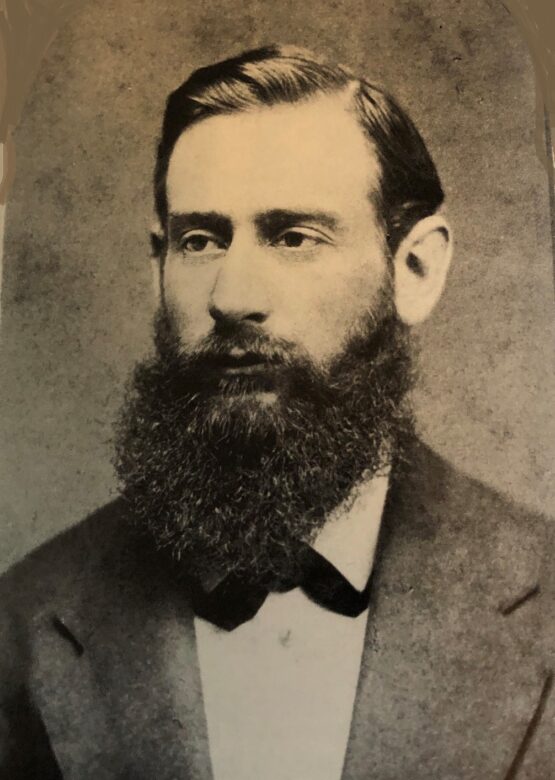

In 1869 Nathanael Herreshoff secured a position as a draughtsman for the Corliss Steam Engine Company in Providence Rhode Island. [3] The Herreshoff family often visited Providence and was acquainted with Mr. and Mrs. John Houghton. Mr. Houghton was a foreman at Corliss and may have brought Nathanael to the attention of George Corliss. Nathanael also boarded at the Houghton's for several years during his time at the Corliss works. This was a premiere position for a person of Nathanael's interests and talents as Corliss was at that time, without question, the foremost manufacturer of steam engines in the United States.[4]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[3] Attachments “A” and “B” Herreshoff Marine Museum, Curator’s Log The Herreshoff Biographies Part four, by John Palmieri

[4] A general Purpose Technology At Work, The Corliss Steam Engine In The late 19th Century, Nathan Rosenberg, Pg 24.

For a person of Nathanael's education, a draughtsman’s position was what in the present day would be termed a designer. Nathanael's first job was tracing some Corliss drawings for William Harris, a former Corliss superintendent, who in 1864 had opened his own company to produce engines under license from George Corliss. However, Nathanael's capabilities were quickly recognized: very soon after starting he was asked by Mr. Edwin Reynolds to assist him indicating a mill engine. In reply to a questionnaire from the Henry Ford Museum in 1931 Nathanael recalled; “Very soon after my connection with the Corliss works, Mr. Reynolds took me out to a mill to assist in applying the steam engine indicators to determine the power used. This work I took quite a liking to and soon attended to all that work and became known about the shops as the Engine doctor. It was a fine schooling for me in Steam Engineering matters.” [10]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[10] Mystic Seaport Museum GW Blunt White LibraryLFH Collection 138 Box 16 Folder 13; 23 of 24

Edwin Reynolds had joined Corliss in July1867 and became General Superintendent in 1871. General Superintendent was the second most senior position in the plant, reporting directly to Mr. Corliss. Edwin Reynolds was trained as a machinist and prior to joining Corliss had been the superintendent at Stedman Co. makers of industrial machinery in Indiana and had worked with John Erickson on the USS MONITOR machinery.[11] Reynolds was also was a very effective salesman and appears to have been held in high regard by Nathanael. In an interview for Brown University in 1933 Nathanael commented: “When I started in, Reynolds was general superintendent and salesman. A crackerjack machinist, inventor and practical man”.[12]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[11] An Industrial Heritage, Allis Chalmers Corporation, Walter F. Peterson, Pg.41.

[12] Series 5, Box 3, Folder 12.1-12.16K George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University the Transcribed interview of NGH by George Hall, W.E. Richardson 12/2/1932

Indicating Responsibilities

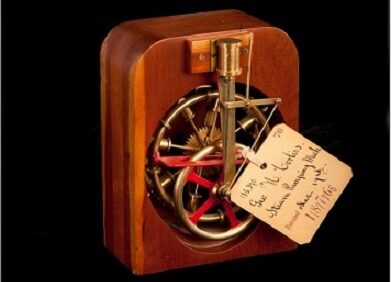

Indicating a steam engine is the equivalent of tuning a modern internal combustion engine for optimum performance. A test instrument called an indicator is connected to the engine to simultaneously record the steam cylinder pressure and the position of the piston within the cylinder. The data is recorded by a pen on a small card resulting in a foot shaped closed curve. This information is then used to adjust the engine's valve linkage to most effectively utilize the available steam pressure. The data recorded on the final indicator card and engine RPM are then used to calculate the engines “indicated horsepower” which was often a contract specification. Indicating a steam engine is usually an iterative process requiring several tests, each followed by a valve linkage adjustment until the optimum curve on the indicator card is achieved.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

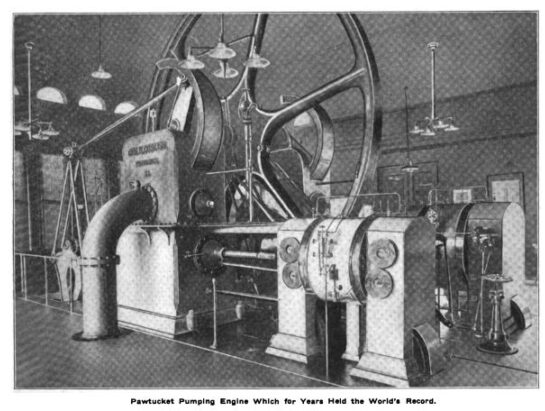

Nathanael's indicating responsibilities would have required travel to the location of an engine and thus provided him with the opportunity to observe a wide variety of industries and how they were set up and operated. The only record of such a trip is one to Nashua, NH where he recalled he needed to improvise a special tool called “lazy tongs” in order to indicate the engine. He later made a nice set for himself and used them when indicating engines.[13] These lazy tongs must have been adopted by others as quite a bit later a published account of the Corliss Pawtucket, RI pumping engine mentions the great accuracy of the indicator cards obtained using Corliss tongs.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[13] Series 5, Box 3, Folder 12.1-12.16K George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University Transcribed interview of NGH by George Hall, W.E. Richardson 3/18/33

George Corliss was a shewed and confident businessman and would frequently offer the customer a new engine with a choice of two forms of payment: cash, or a price based upon a multiple of the reduced cost of coal consumed by the new Corliss engine as compared to that of the engine it replaced.[14] It was therefore vital to the Corliss Steam Engine Company's financial success and reputation that a new Corliss engine was indicated to perfection (i.e., working at peak efficiency). As it was typical for a Corliss engine to use only two-thirds to one-half the amount of coal consumed by the engine it replaced, those customers that elected the one-time cash payment invariably made the better decision. However, if a potential customer did not have or could not borrow the money for a single payment, this system would permit Corliss to sell an engine and the customer would acquire a superior machine. Until the Corliss patents expired in 1870 George Corliss licensed others in this country and in Europe to build engines incorporating his patents. One the largest was Miller and Allen in Chester PA, who made Corliss engines for iron and steel rolling mills.[6] The license fee was based upon the area, in square inches, of the engine’s piston. The patents were in Corliss’s own name and not that of his Company and Mr. Corliss charged the Corliss Steam Engine Co. the same licensing fee.[14]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[14] Iron Age magazine, December 4, 1902, Pg. 36d.

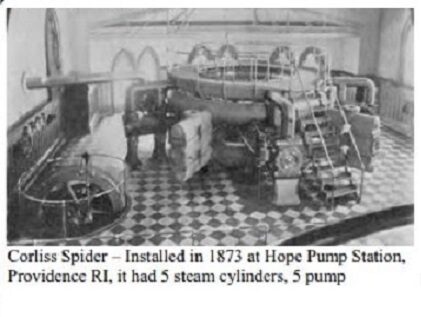

In 1873 Nathanael assisted George Phillips with the drawings for the Hope Station water pumping engine designed by George Corliss for the city of Providence (George Phillips became a very close friend and later joined Nathanael at the Herreshoff Manufacturing Company). This pumping engine, the first of only five pumping engines produced by the Corliss company, was placed in service October 4, 1873. It was a very ingenious and complicated radial steam pump consisting of five interconnected steam cylinders and five pump cylinders and was known as “the spider”. The pump was designed to automatically vary its speed as necessary to maintain a constant pressure on the water mains without the aid of a standpipe. The machine performed its intended function but had problems - some design-related, others political. The pump proved to be noisy and used an excessive amount of coal but after a contentious process was finally accepted by the City of Providence. The pump was removed from service in 1896.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

Nathanael did not think highly of this engine but recalled that he learned much from it.[12],[15] Mr. W.H. Odell, a witness for the Hope Engine acceptance tests, met Nathanael and later wrote in Power magazine “Mr. N.G. ('Nat') Herreshoff, who in later years became the world's most famous builder of fast sailing yachts, etc., but at that time one of the brightest men employed by Mr. Corliss; and there were a lot of them who later on wrote their names high up on the lists as mechanical engineers”.[16] Another trade publication of the day credited Nathanael with designing the reducing linkage necessary to accurately measure the stroke of this unusual engine. George Corliss recognized some of this engine’s deficiencies and built an experimental pumping engine in a new building at the Corliss plant to investigate the problems.[17] While Nathanael was in Europe in 1874 his older brother John wrote him regarding this experimental engine: “stopped by at Corliss to see new pumping engine which has some good, some bad features”[18].

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[12] Series 5, Box 3, Folder 12.1-12.16K George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University the Transcribed interview of NGH by George Hall, W.E. Richardson 12/2/1932

[15] Ibid.

[16] Folder Subject: Article in 'Power' on George Corliss. HMM Subject Files, Folder 53 (new), 209 (old) 1923-04-08.

[17] National Engineer magazine March 1903, Pg 5.

[18] Recollections and Other Writings by Nathanael G. Herreshoff. Ed. Carlton J. Pinheiro,Pg 24.

A Much-Needed Break

As was the practice of the time the Corliss plant worked a ten-hour day six days a week. In spite of this schedule Nathanael worked nights and Sundays performing design and engineering work in support of his brother John's boat building business and often raced John's yachts. During the 1870s John's business was increasing in both volume and complexity as the vessels were becoming larger and powered by steam. Nathanael designed the engines and produced the many drawings required to build the engines as well as modeling hulls. George Corliss generously permitted Nathanael to use the Corliss shop facilities for this work and in November 1870 he carved the model for his famous sloop SHADOW in the Corliss pattern shop.[19] I have found no evidence that Nathanael ever received any compensation for the considerable work he performed for John while at either MIT or Corliss. The long-established tradition of servitude was both expected and accepted. The extra work required to support John's business continued to increase and in 1874 Nathanael became exhausted and quite ill. In his words: “I got sick and was laid out in bed. Had doctor working over me. Was put to bed and had to quit work for some time. Family sent me to Europe to rest up.”[20] With the help and urging of his concerned family, principally his mother, it was arranged that Nathanael visit his brother Lewis, then in France.[21] He left New York on February 10, 1874 aboard the steamer GOETHE for Cherbourg, France arriving February 20th and then went by train to meet Lewis in Paris. Later they both went to Nice to visit their cousins, the Eatons. Nathanael and Lewis built two small boats in Nice and took the 16-foot RIVIERA on the well documented and adventurous trip northward on the rivers of western Europe, ending up in Rotterdam. Shipping Riviera as deck cargo they proceeded by steamer to London then Liverpool. They left Liverpool on September 1, 1874 on the steam ship CITY OF BRUSSELS, arriving in New York in eight and a half days. From New York they set sail for home in the RIVIERA, arriving in Bristol on September 24, 1874.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[19] Series 5, Box 3, Folder 12.1-12.16K George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University Transcribed interviews of NGH by George Hall, W.E. Richardson 12/2/1932.

[20] "The Log of the Riviera." Within; Recollections and Other Writings by Nathanael G. Herreshoff. Bristol, 1998, Pinheiro, Carlton J. (ed).

[21] Boat Builders of Bristol, Samuel Carter III, Pg. 48

Nathanael did not neglect his professional career or self-improvement while in Europe: he visited cultural sites as well as shipyards and manufacturing plants and - significantly - investigated Europe's more advanced steam pumping engines. Nathanael and Lewis then spent three weeks in London sight-seeing. While in London Nathanael purchased John Scott-Russel's three volumes “The Modern System of Naval Architecture” and had a pocket-sized logarithmic slide rule made to his specifications.[21] This eight-month trip was financed by various members of the family but principally by Nathanael's oldest, very successful, brother James.[22]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[21] Boat Builders of Bristol, Samuel Carter III, Pg. 48

[22] Series 5, Box 3, Folder 12.1-12.16K George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University the Transcribed interviews of NGH by George Hall, W.E. Richardson 12/2/1932, Pg.1.

Upon his return to work at Corliss Nathanael was placed in charge of testing the experimental engine Mr. Corliss had designed and built in his absence. It was perhaps news of this assignment that prompted Nathanael's younger brother John Brown Francis to write “I am glad Corliss is finally recognizing your ability and value to him.” This experimental engine was another complicated radial design consisting of a circular array of ten pump cylinders connected by geared linkage to a single large steam cylinder. [23]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[23] December 4, 1902 issue of Iron Age magazine, Pg. 36c

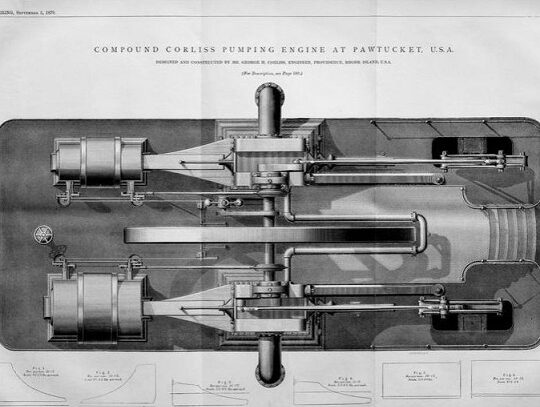

Although this engine proved to be an improvement on the Hope engine, Nathanael, based upon his testing and calculations, was able to convince Mr. Corliss it had such great friction as to be uneconomical.[24] The pump was dismantled and in 1875 and a second experimental pump was built in the basement of the Corliss plant. This second experimental engine was designed in large part by Nathanael and incorporated features he had observed on pumping engines in Europe. George Phillips later wrote “Mr. Herreshoff had recently returned from Europe where he had seen many compound engines and it was largely due to his urgent advice that Mr. Corliss made this a compound engine.”[25]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Series 5, Box 3, Folder 12.1-12.16K George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University un-transcribed interviews of NGH by George Hall, W.E. Richardson 12/2/1932 & 3/18/33

This engine was a compound horizontal walking beam engine with steam jacketed cylinders. It was the Corliss works first engine to incorporate these features. The pump cylinders were in line with and directly connected to the steam cylinders. The pump's valve design was also new and consisted of a large number of small, light, spring actuated valves which opened and closed easily. Each pump cylinder had 280 valves made of three-inch diameter spring loaded copper disks with rubber seats. This design had less friction and produced better flow than prior pump valves. It is likely Nathanael learned of this valve design while in Europe. This pump engine proved to be a great improvement and was later sold to a waterworks in Easton PA.[26] There is little question that what Nathanael learned from observing pumping engines in Europe and the testing and development work he performed on the two Corliss experimental engines benefited his career at Corliss and significantly advanced the design of Corliss engines.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[26] Their Last Letters 1930-1938: Nathanael G. Herreshoff and William P. Stephens, Pg.74.

The Centennial Engine

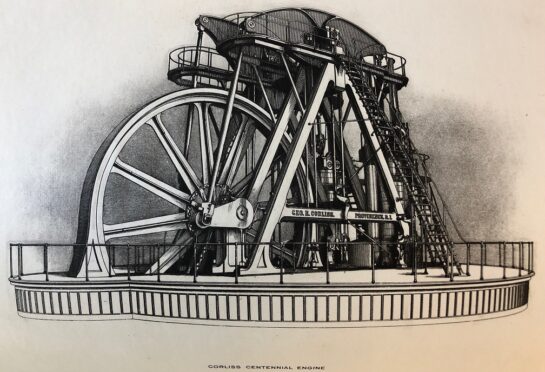

At 27 years old and with less than 6 years of experience at Corliss, Nathanael was selected to participate in the design of what would be - at that time - the largest steam engine in the country. He was later unexpectedly entrusted with the start-up of this engine at the opening of the Centennial Exhibition held in Philadelphia from May10, 1876 - November 10, 1876. [27] In his words, “I was one of a few that assisted and worked out the design of the then great Corliss Engine at the Centennial Exposition in [18]76 that you admired and had charge of it for starting up at time of opening.”[28] The Centennial Exhibition of 1876 was, for all practical purposes, the first serious attempt to hold an industrial exhibition in the United States.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[27] Series 1, Box1, Folder 1.26 George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University

[28] Series 1, Box 1, Folder 1.30-1.32 George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown

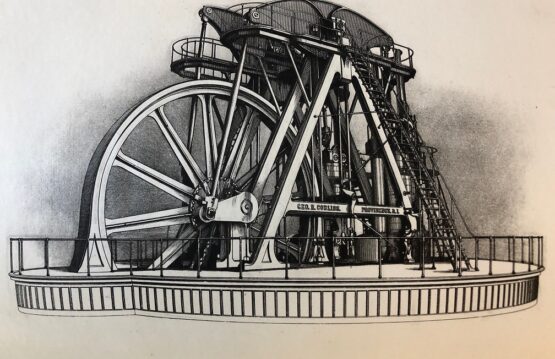

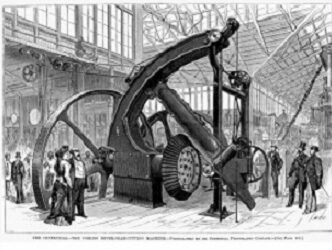

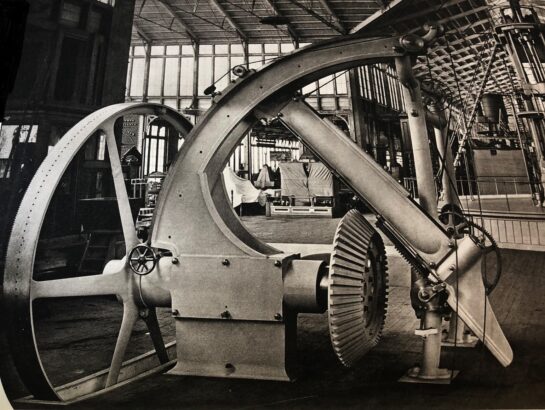

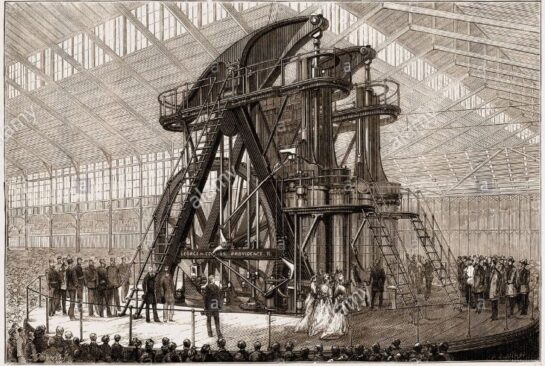

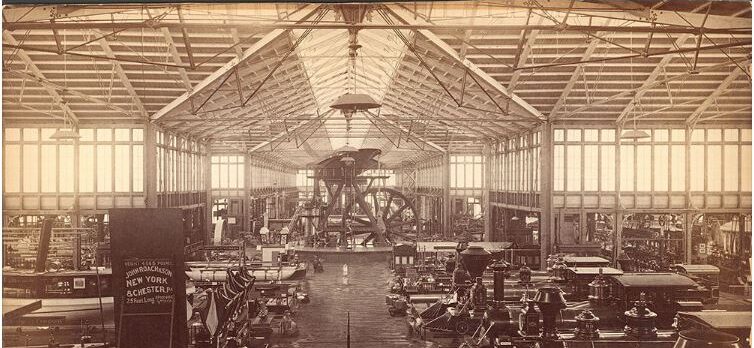

It is difficult to describe how very important the success of this engine was to George Corliss personally. On February 19, 1872 President Grant appointed George Corliss as one of two commissioners from Rhode Island on the Centennial Commission.[29] He was later elected to the Commission's 13-member Executive Committee which carried out most of the Commissions responsibilities. During a meeting of the Executive Committee in January 1875 Mr. Corliss proposed to fulfill the Commission's responsibility to supply the motive power required to operate the exhibitors’ machinery in the 13 acre Machinery Hall. His proposal to provide a single large steam engine boilers and all necessary shafting and piping was approved by the Executive Committee. Politics became involved and the proposal was rejected by the Commissions Finance Committee, which was dominated by Philadelphians who did not believe a single engine could do the job, and wanted to instead use several engines to be built in Pennsylvania. Mr. Corliss then withdrew his proposal. A protracted delay produced no other capable suppliers and finally, five months later, in May 1875 a meeting of the full Commission voted unanimously to ask Mr. Corliss to resubmit his proposal. He did so and proposed to furnish and set-up the engine at no cost to the commission as the engine would be the Corliss Company's exhibit. He proposed the sum of $77,000 to furnish and install the boilers, shafting and piping required to transmit the power from his engine to exhibitors throughout Machinery Hall. The $77,000 figure was later raised to $79,006.25 when he was asked to also provide power to the pumps in the Hydraulic Annex adjacent to Machinery Hall.[30], [31] Contract arrangements were completed on June 4th 1875 and Mr. Corliss immediately telegraphed the plant from Philadelphia: “Proposals accepted. Terms satisfactory. Tell the foremen to clear the decks, ready for action on my return.”[32] The contract between the Corliss Steam Engine Company and the Centennial Commission stipulated the engine be operational no later than April 10th - one month before the scheduled opening of the exhibition. All the work was completed on time and when the costs exceeded this contract with the Commission Mr. Corliss paid the overage out of his own pocket. The first pencil sketch of the machinery was made by Mr. Corliss on June 14, 1875. [33] Mr. Corliss recognized a significant public relations opportunity when he saw one and from the outset intended for this engine to become the centerpiece of the exhibition. He succeeded. The engine became the icon of the 1876 Exhibition, and henceforth was known as the Centennial Engine.[34] Everything about this engine was massive. It was at the time the largest stationary steam engine in the United States and the most powerful engine the Corliss works would ever build.[35] It was described as majestic, and standing 40 feet in the air it could be seen from all parts of the immense Machinery Hall. Its metal surfaces were nicely finished - some even polished - but there were no decorations or fancy paint work. The presentation of the engine (and it was a presentation) was greatly enhanced by concealing the engine’s foundations, 18-inch steam piping, and valves beneath a large and attractive 55-foot-diameter, 3.5-foot-high platform built around the engine.[36] The engine was easily approached from all sides by visitors with its almost silent workings open to view. Although usually spoken of in the singular it was in fact a pair of single cylinder engines coupled by a common crank-shaft to a single fly wheel set between the engines. The complete description of the machine was a vertical duplex double-acting condensing walking beam steam engine.[37]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[29] Series 2, Sub Series S, Box 1, Folder 4.19, George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University.

[30] Series 4, Box 5x, Folder b, George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University

[31] Scientific American Supplement, 1876 # 26. Pg. 403.

[32] A general Purpose Technology At Work, The Corliss Steam Engine In The late 19th Century, Nathan Rosenberg, Pg.7.

[33] New England Wireless and Steam Museum- https://newsm.org/steam-e/corliss-centennial-engine/

[34] The Great Centennial Exhibition Phillip T. Sandhurst, Pg. 365-369.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Pg. 2 Series 5, Box 3, Folder 12.1-12.16K George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University Transcribed interviews of NGH by George Hall, W.E. Richardson 12/2/1932.

The engines steam-jacketed and insulated cylinders had a bore of 44 inches and a piston stroke of 10 feet. The 30-foot-diameter flywheel weighed 56 tons and was made up of 12 cast segments bolted together at the hub and rim. The crankshaft bearings were 18 inches in diameter and 216 gear teeth cut into the 2 foot face of the flywheel made it the largest cut gear of its time. This large gear drove a 10-foot-diameter 8.5 ton pinion gear located out of sight in a pit below floor level. The 27-foot-long cast walking beams each weighed about 11tons.[38] The total weight of the engine, shafting, gears, boilers, piping and other Corliss supplied equipment was estimated at 607 tons This engine was the first to use the vacuum dashpots that Nathanael had recommended to George Corliss to more rapidly close an engines steam inlet and exhaust valves.[39]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[38] Scientific American, Supplement 1876 #26, Pg. 403.

[39] Ibid.

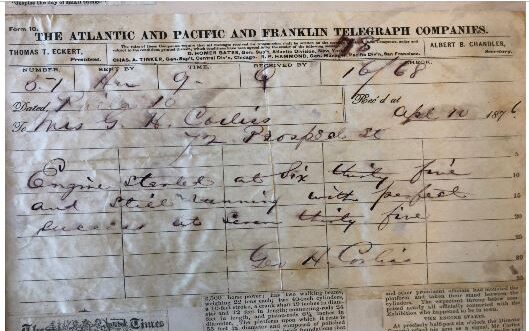

This enormous machine and associated equipment was designed, built, shipped to Philadelphia and then assembled and tested in just nine months and 26 days from the date of the contract. The Providence Journal reported more than 200 workers were added to the company’s payroll to complete the engine on time. 10 trains of six cars each were required to ship the engine, shafting, gears, pulleys, boilers and pipe to Philadelphia.[40] The first train left Providence on November 15, 1875 and the last shipment on March 22, 1876, just 19 days before the engines operational date of April 10th 1876.[41] Construction of the Machinery Hall, the second largest building on the exhibition grounds, started in late January 1875, and was turned over to the Commission in December 1875. Foundations for Corliss engine were being constructed in early January 1876 and by the end January portions of the engine castings were in place and other parts of the engine were on site. The Philadelphia Evening Telegraph Bulletin reported setting up the engine was proceeding night and day. In early March, the engine was assembled and the underground transmission shafting laid out on the floor ready for installation.[42], [43] The engine, as required by Mr. Corliss’s contract with the Centennial Commission, was first started on April 10,1876, 30 days prior to the opening of the Exhibition. George Corliss telegraphed his wife: “Engine started at six thirty five and still running with perfect success seven thirty five”.[44]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[40] Scientific American,Supplement 1876 #3, Pg 38.

[41] Scientific American,Supplement 1876 #9, Pg.130.

[42] Series 4, Box 5x, Folder b, Corliss Collection Hay Library, Brown University.

[43] Scientific American Supplement 1876 # 9, Pg.130.

[44] Ibid.

This was the first time the engine had ever been run as there had been insufficient time available for shop tests in Providence. The engine required just 14 pounds of steam pressure to turn over. It is clear additional work on the engine was required as it was reported in the May 6, 1876 issue of the Scientific American Supplement that final painting remained although that observation was likely made sometime in late April. This was clearly a very intensive project as illustrated by the last shipment of parts having left Providence just 19 days before the April 10th required engine start date. The reported “setting up the engine working night and day” and the late day engine start time of 6:35 p.m. on April 10th indicate the installation of engine and shafting was a hectic undertaking.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

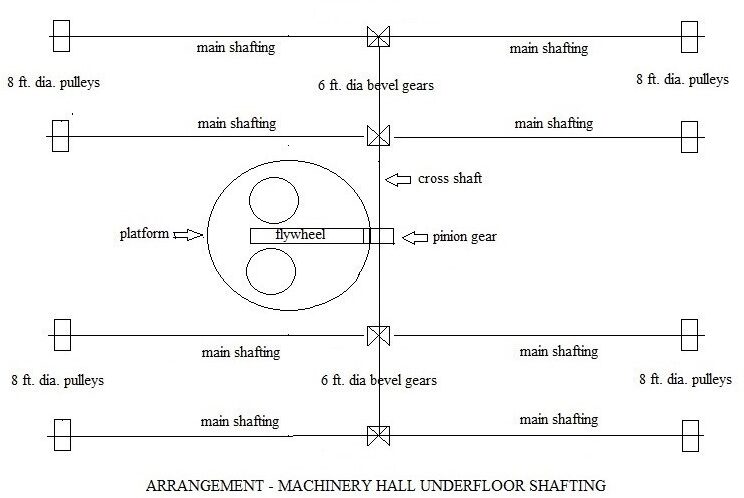

Power was transmitted from the engine's ten-foot-diameter pinion gear to the exhibitors’ machinery by a complex array of shafting in tunnels beneath the floor of Machinery Hall. The design of this underground shaft arrangement incorporated four sets of bevel gears six feet in diameter. Bevel gears of this size had never before been manufactured but Corliss cast the gear blanks and designed and built a special gear cutting machine to produce them. Each of the four gear sets consisted of three bevel gears and bearings set on large foundations within the trenches. The engine’s 10-foot diameter pinion was mounted on a 252-foot cross-shaft on which the four sets of bevel gears were mounted. The bevel gears in turn drove eight 658-foot-long main distribution shafts. Power was transmitted from the underground shafting to the overhead line shafting by eight-foot diameter pulleys having 32-inch-wide faces. Each pulley employed two16 inch wide leather belts to connect the hidden main shafts to the overhead line shafting. The exhibitors’ machinery was then connected by additional leather belting to the overhead line shafts. The large leather belts rising through the floor from the main shafts to the overhead line shafting were enclosed in glass cases to both provide visibility and protect the visitors. The fly wheel and pinion gear were reported to have emitted a slight murmur and the bevel gearing a slight rumble which could barely be heard when the exhibitors’ machinery was operating. The below grade shafting, bevel gears and bearings weighed approximately 200 tons. The total length of all shafting supplied by Corliss was approximately 10,400 feet.[45]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[45] Scientific American Supplement 1876 #19, Pg.294.

A separate boiler house, accessible to the public, was constructed adjacent to Machinery Hall to house 20 Corliss designed vertical fire tube boilers. Eight of the boilers were designated for the Corliss engine and eight to supply steam to the pumps in the Hydraulic Annex. The other four were spares. One reporter described the Corliss boiler house as “the most complete and accessible arrangement as well as the most orderly looking place of the kind ever seen by the writer.”[46] The engine only required the use of three to four of the boilers during the Exhibition. Steam was supplied from the boiler house to the engine by 320 feet of 18-inch insulated pipe located in a tunnel beneath the floor of Machinery Hall. [47]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[46] Series 5, Box 3, Folder 12.1-12.16K George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University Transcribed interviews of NGH by George Hall, W.E. Richardson 3/18/33, Sheet 1.

[47] The Illustrated History of the Centennial Exhibition James D McCabe 1876, Pg. 304-305.

I have been unable to find any information regarding how many Corliss employees were sent to Philadelphia to work on or supervise the installation of the Corliss equipment. It is likely local Philadelphia contractors and tradesmen were employed under Corliss supervision to perform some of the work; in addition to the mechanical work there was considerable excavation, foundation and rigging work required. In the1933 interview for Brown University Nathanael mentions the name of one Corliss foreman who went to Philadelphia. “Mr. J. Reed was the pattern foreman. He devised and superintended the gallows went down to Philadelphia and although the job was somewhat out of his line, he was very successful. A good man.”[48] The scope of the project and its importance to Mr. Corliss would suggest to me there were certainly additional Corliss employees both performing and supervising the installation work in Philadelphia.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[48] Series 5, Box 3, Folder 12.1-12.16K George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University Transcribed interviews of NGH by George Hall, W.E. Richardson 3/18/33.

George Corliss used his position on the executive committee to be certain his engine played a major role in the opening and closing ceremonies of the exhibition. At the time nothing signaled technical sophistication and industrial progress more than steam power and he carefully orchestrated the moment the Corliss Engine was to come to life. The opening ceremonies began at 10:15 a.m. on May 10th with much music, many speeches and a 100-gun salute. Immediately following the formal opening of the Exhibition by President Grant the President and other dignitaries marched to the adjacent Machinery Hall and mounted the platform surrounding the great engine. They were received by Mr. Corliss, who instructed them how to start the engine. Upon a hand signal from Mr. Corliss President Grant and Emperor Don Pedro of Brazil each turned a silver-plated lever to start the engines and at 1:20 p.m. set in motion the nearly fourteen acres of machinery.[49] During this time Nathanael and one of the operating engineers were stationed beneath the platform with a duplicate set of controls in the event anything went wrong. [28], [50] The silver-plated handles used to start the engine are preserved within the Corliss Collection of the Hay library at Brown University.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[49] Series 5, Box 3, Folder 12.1-12.16K George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University un-transcribed interviews of NGH George Hall, W.E. Richardson 3/18/33.

[50] Engineering News and American Railway Journal, Volume 35

[28] Series 1, Box 1, Folder 1.30-1.32 George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown

Nathanael's day would have started early on opening day as it requires several hours to gradually bring a large steam driven machine up to operating temperature before placing it in operation.[51] As an additional element of the engine’s presentation during the exhibition the operating engineer, in a bowler hat, was seated in a chair front and center on the platform reading a paper or magazine. Occasionally he would set the paper down, climb the stairs and oil and wipe down some part of the engine.[52] The engine ran the entire six months of the exhibition without the slightest incident or fault.[53] Meanwhile the real work required to keep the engine running was being done out of sight in the boiler house where the boiler tenders and firemen were controlling the water level in the boilers, stoking coal and raking clinker during what was an unusually hot summer.[54]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[51] The Illustrated History of the Centennial Exhibition James D McCabe, Pg. 901.

[52] The Illustrated History of the Centennial Exhibition James D McCabe, Pg. 899

[53] Julia Herreshoff letter to Caroline Herreshoff, Herreshoff Family Collection, Herreshoff Marine Musem.

[54] Recollections and Other Writings by N.G. Herreshoff, Pinheiro, Carlton J. (ed.) Pg. 25.

My research has led me to conclude Nathanael Herreshoff was very involved with both the design and start-up of the Corliss Centennial Engine but was not, as very often written, involved with assembly of the engine in Philadelphia. There are four documents written by Nathanael himself and two interviews in which he discusses his involvement with the Centennial Engine but not once does he mention having been in charge of or participating in the assembly of the engine in Philadelphia.[3],[12],[13],[19],[28]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[3] Attachments “A” and “B” Herreshoff Marine Museum, Curator’s Log The Herreshoff Biographies Part four, by John Palmieri

[12] Series 5, Box 3, Folder 12.1-12.16K George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University the Transcribed interview of NGH by George Hall, W.E. Richardson 12/2/1932

[13] Series 5, Box 3, Folder 12.1-12.16K George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University Transcribed interview of NGH by George Hall, W.E. Richardson 3/18/33

[19] Series 5, Box 3, Folder 12.1-12.16K George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University Transcribed interviews of NGH by George Hall, W.E. Richardson 12/2/1932.

[28] Series 1, Box 1, Folder 1.30-1.32 George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown

In a letter to her daughter Caroline dated May 4, 1876 Nathanael's mother, Julia Herreshoff, wrote “I think I wrote you about Nat leaving us suddenly for Philadelphia to attend to the Corliss machinery.”[55] In the un-transcribed notes of the March 25, 1833 interview for Brown University Nathanael uses the words “detailed to start up unexpectedly to me”[50] in reference to his assignment to start-up the engine at the opening of the Exhibition. Had Nathanael been in charge of both the assembly and starting of the engine his start up assignment would not have been unexpected or his travel sudden. Halsey Herreshoff’s remark during a Herreshoff Maritime Museum lecture July 2014 to the effect Nathanael's assignment to Philadelphia was the result a foreman becoming sick provides the key to understanding why Nathanael's departure for Philadelphia was sudden and his assignment unexpected. Julia Herreshoff’s letter provides an indication of the timing of that assignment. Nathanael was justly proud of his involvement with the Centennial Engine and had he participated in the erection of the engine in Philadelphia he would certainly have made mention of it as he did with his involvement with both the engine’s design and start-up.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[55] The Illustrated History of the Centennial Exhibition James D McCabe, Pg. 475.

[50] Engineering News and American Railway Journal, Volume 35

Nathanael stayed in Philadelphia several days following the opening ceremonies and later that summer traveled to the Exhibition by boat with members of his family. Nathanael, Lewis and their father, Charles Frederick, went in the 22-foot catboat SPRITE. John, James and others went in John's new 46-foot steamer VIOLET.[56] Nathanael returned again to Philadelphia shortly before the engine was shut down to conduct some experiments and take measurements of the engine’s performance. Based on those measurements and the record of coal consumed he calculated the engines actual load had varied between 350 and 400 HP.[50] The engine was designed to produce 1400 HP at 60 pounds or 2500 HP at 80 pounds steam pressure.[57]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[50] Engineering News and American Railway Journal, Volume 35

[56] The Illustrated History of the Centennial Exhibition James D McCabe, Pg. 864, 882, 883.

[57] Bulletin of the Business Historical Society #23, January 1930, Pg. 6.

As with the opening ceremonies George Corliss arranged to have his engine play a symbolic role at the closing of the Exhibition. The attendance closing day was one of the largest of the exhibition and a huge crowd had gathered around the Corliss engine expecting to see the President turn the valves to shut down the engine. The closing ceremonies on the 10th of November had been planned to be outside and proceed much as the opening ceremonies but due to inclement weather were moved into the Judges Hall. The ceremonies began at just after 2 p.m. with the arrival of President Grant who was joined by members of his Cabinet, the Supreme Court, members of Congress and many Governors. After many speeches and much music President Grant was introduced, stood and simply said “Ladies and Gentlemen: I have now the honor to declare the exhibition closed” and upon a wave of his hand a telegraph signal sounded a gong at the operator’s station in Machinery Hall as a signal to stop the engine. At 3:37 p.m., the great engine stopped.[58] After the Exhibition closed, the engine, shafting and bevel gears were dismantled and shipped back to the Corliss works in Providence, Rhode Island. George Corliss’s total out of pocket costs for the engine including the overages on his contract with the Commission was in excess of $100,000[59], the equivalent of $2,475,486 in 2021 dollars.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[58] Their Last Letters 1930-1938: Nathanael G. Herreshoff and William P. Stephens, Pg.74.

[59] Letter from N. G. Herreshoff to L. F. Herreshoff May 7, 1929. Mystic Seaport Museum, L. Francis Herreshoff Collection 138, Box 17, Folder 5, Pg 4.

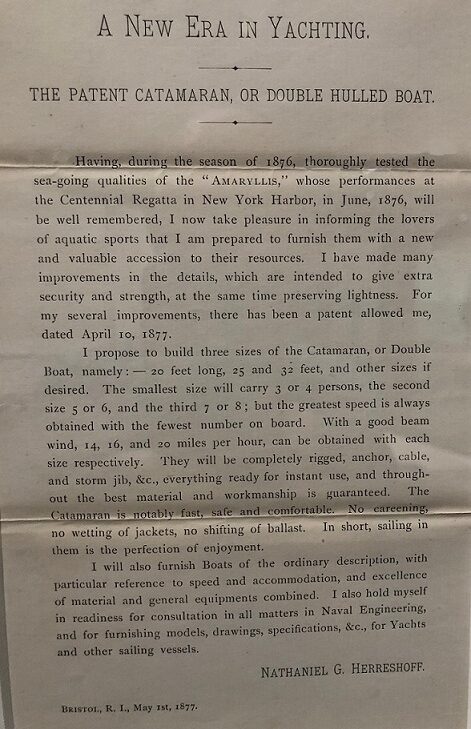

Two Furloughs

Upon his return from Philadelphia in mid-May, 1876 Nathanael obtained a furlough from Corliss which extended well into summer to launch, sail and famously race his new catamaran AMARYLLIS which he had his brother John build during the previous winter.[60] AMARYLLIS attracted considerable attention that summer with several individuals expressing interest in acquiring similar catamarans. As a result of this interest Nathanael, in the spring of 1877, obtained a three month leave of absence from Corliss to enter into business for himself building catamarans in a space at his brother’s shops. His advertised services however extended beyond catamarans to “boats of ordinary description” and services as a marine engineer. It proved to be an unprofitable undertaking and Nathanael returned to Corliss.[61],[62]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[60] Recollections and Other Writings by Nathanael G. Herreshoff. Ed. Carlton J. Pinheiro.

[61] Engineering News, January 18 1890, Pg. 10.

[62] American Machinist magazine, September 1878, Pg. 9.

Immediately following the Centennial Engine the Corliss Co. designed and built a larger and improved version of the second experimental pumping engine for the City of Providence's Pawtucket pump station. As Nathanael had a large part in the design of the Centennial Engine and the successful second experimental engine which incorporated many of the features he had observed in England it is reasonable to believe he was working on the design of this engine before he was sent to Philadelphia. Although this engine incorporated many features of the Centennial Engine and in some ways resembled the Centennial Engine laid on its side, it was very different. The Pawtucket Engine was a compound engine with the high-pressure cylinder on one side of the flywheel and the low-pressure cylinder on the other. The two pumps were in line with and coupled to the steam cylinders. In addition, this engine was designed to use 125-pound superheated steam, a significantly higher steam pressure and temperature than any previous Corliss engine. The Pawtucket pumping engine proved to be a very efficient machine. It exceeded its contract performance requirements by 30% and was the subject of many articles in the trade journals of the day.[63],[64],[65] W.H. O’dell in the February 1879 issue of the American Machinist Magazine wrote “This engine presents greater attention to details than any other engine that has come under our personal notice, as well as because its economical features can, and doubtless will be applied to mill engines.” The efficiency achieved was declared to be unprecedented by the independent test engineers hired by the city of Providence to perform the acceptance tests. The installation of the Pawtucket pumping engine was completed in1878 shortly after Nathanael left Corliss.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[63] American Machinist magazine, October 1878, Pg. 8.

[64] Recollections and Other Writings by N.G. Herreshoff, Pinheiro, Carlton J. (ed.) Pg.25.

[65] Patent No.125084 Improvement in Governors for Steam Engines March 26, 1872.

In May of 1877 Nathanael's brother John obtained a contract to build the 120-foot steamer ESTELLE on a very short schedule. Nathanael took another leave of absence to model the hull and design an engine that would drive the boat at a contracted speed of 16 miles per hour.[66] I have not been able to determine the actual length of this leave. Nathanael also conducted ESTELLE's trials in late October and early November 1877. In June 1877 while Nathanael was on leave a major development occurred at Corliss; Edwin Reynolds, the General Superintendent and salesman, left his $5,000 position at Corliss to begin work on July 1st at the Reliance works of the E.P. Allis Co. in Milwaukee, Wisconsin at a salary of $3,500.[11] This must have been most unwelcome news as Nathanael thought a great deal of Mr. Reynolds and shared a patent for an improved engine governor with him.[12],[67] An incident which occurred in 1876 may have set the stage for this resignation: Reynolds took an order from the Trenton Iron works for an application that required a 500 hp engine with a guaranteed speed of 160 rpm. At the time, Corliss engines ran at no more than 80 rpm. Mr. Corliss refused to book the order but when Reynolds insisted he relented saying “I wash my hands of any and all responsibility in the matter. You can have all the credit and discredit that comes with attempting such a foolish piece of engineering.”[68]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[66] Success Volume 6 Dec. 1903, Pg. 747.

[67] The Valve World, magazine, March 1910, Pg.447.

[68] Patent 183054 issued October 10, 1876.

[11] An Industrial Heritage, Allis Chalmers Corporation, Walter F. Peterson, Pg.41.

[12] Series 5, Box 3, Folder 12.1-12.16K George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University the Transcribed interview of NGH by George Hall, W.E. Richardson 12/2/1932

Reynolds succeeded and the engine was placed in service in 1877 shortly before Reynolds left Corliss. One magazine reporting on Reynolds leaving Corliss wrote “The attitude of Mr. Corliss probably had much to do with Mr. Reynolds leaving Corliss. Mr. Corliss thought the Corliss engine was practically perfect and no chance existed for further development.[69] Nathanael's failed effort to establish his own business in the spring of 1877 is an indication he may also have been thinking of something beyond the Corliss Co. George Corliss was by all accounts, including Nathanael’s, a very fine man who paid and treated his employees very well, but as Nathanael related “his great peculiarity was he wanted to be the boss and wanted no one else to bother with inventions…” and “his weakness was he had to be the king pin.”[12] In the April 1903 issue of Modern Machinery magazine Reynolds recounted “I knew that with Edward P. Allis and his Reliance works, small as they were at the time, I should have the opportunity to expand my ideas which would never be the case in the Corliss works.” When Nathanael was performing experiments for the Centennial Engine he showed Mr. Corliss how using vacuum to close the steam inlet and exhaust valves would be faster than the weights currently in use. Corliss replied he tried that many years ago and it would not work but later came to Nathanael with a sketch of the same thing, saying “that's what we want.”[12] (Faster acting valves improve efficiency). The Centennial Engine was the first to incorporate vacuum pots for closing the steam inlet and exhaust valves. Vacuum pots later became the industry standard and was another of the developments that permitted higher speed, more powerful steam engines.[12], [10]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[69] Recollections and Other Writings by Nathanael G. Herreshoff. Ed. Carlton J. Pinheiro, Pg 28.

[12] Series 5, Box 3, Folder 12.1-12.16K George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University the Transcribed interview of NGH by George Hall, W.E. Richardson 12/2/1932

[12] Series 5, Box 3, Folder 12.1-12.16K George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University the Transcribed interview of NGH by George Hall, W.E. Richardson 12/2/1932

[12] Series 5, Box 3, Folder 12.1-12.16K George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University the Transcribed interview of NGH by George Hall, W.E. Richardson 12/2/1932

[10] Mystic Seaport Museum GW Blunt White LibraryLFH Collection 138 Box 16 Folder 13; 23 of 24

Nathanael's oldest brother James’s invention of his coil boiler in 1874 (patent issued in 1876[70]) had a profound effect on the future of his brothers John (J.B.) and Nathanael. The boats John built and equipped with James’s coil boiler and Nathanael's engines and hull designs were safer and faster than anything else available. The performance and quality of these steamers attracted considerable attention.[71] John launched just three steamers 1873 and two in 1874 but with the introduction of the coil boiler the numbers began to increase, 1875 saw the launch of four steamers followed by 11 in 1876 and seven in 1877.[72] The lower number in 1877 was likely the result of the large workload associated with the large 120-foot steamer ESTELLE designed and built that year. The design and engineering effort associated with this rapid increase in John's business placed ever increasing demands on Nathanael's time and energy. Thus in accordance with the desires of his family, his ingrained sense of obligation to J.B., and recognizing the opportunity to pursue his own ideas regarding steam engineering and design, Nathanael resigned from Corliss in December 1877. On January 1, 1878 he entered into partnership with his brother John to form the Herreshoff Manufacturing Co. at a salary of $1,000 vs. his $1,400 Corliss Salary. In “Recollections” Nathanael wrote “it was apparent John need my full service, so I reluctantly resigned from Corliss Steam Engine Co. on December 31, 1877.”[71] This may not have been an easy decision, there are two passages in the book “May the Best Boat Win” where the author indicates Nathanael was seriously considering accepting a competing industrial job opportunity and discussed the matter with his mother.[73] I am not aware of any primary source material which substantiates this or other job offers; the author of the book does however acknowledge as source material interviews with several close family members. In his book “The Wizard of Bristol” Nathanael's son, L. Francis Herreshoff, also alludes to Nathanael having other steam industry opportunities.[74]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[70] MIT Museum,Haffenreffer-Herreshoff Collection, Herreshoff Manufacturing Company Design Record

[71] “May the Best Boat Win,” Pg.124,125, 208

[71] “May the Best Boat Win,” Pg.124,125, 208

[72] Capt. Nat Herreshoff: The Wizard of Bristol, Pg. 94.

[73] Mystic Seaport Museum GW Blunt White Library LFH Collection 138 Box 16 Folder 13; 2 of 24

[74] Capt. Nat Herreshoff ; The Wizard of Bristol Pg. 76

I am thus inclined to believe this to be a reasonable representation of circumstances surrounding the founding of the Herreshoff Manufacturing Co.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

Authors Note:

There is no question that Nathanael's oldest brother James Brown Herreshoffs invention of the coil boiler and the resulting increased demand for John's boats fitted with those boilers created the opportunity for Nathanael to practice steam engineering on his own terms at Bristol. James was not however involved in any direct way with the founding or operations of the Herreshoff Manufacturing Co. Nathanael's relationship with this very talented and successful brother, 14 years his senior, was contentious and Nathanael minimized the role the coil boiler played in the early success of the Herreshoff Manufacturing Company. In a letter dated April 27, 1926 Nathanael wrote;“ The coil boiler had only a precarious life of 6 years and was absolutely dead before the H.M.Co. gained any world wide reputation and “It was entirely given up in spring of 1880”[75] The Herreshoff Manufacturing Co. Construction Record indicates otherwise. With modifications by Nathanael the coil boiler was used for 10 years from 1874 [# 14 VISION] until 1884 when the square boiler of Nathanael's design then became the standard. The coil boiler was fitted to boats for the U.S. Navy, as well as the British and Russian Navies. Some engines and boilers were sold to customers who had hulls built elsewhere. By my count the company manufactured a total of 89 coil boilers.[72] There may also have been a few built for shoreside applications. It is certainly true the coil boilers, particularly in larger sizes, were difficult to build and therefore expensive as well as hard to properly maintain.[76] The coil boiler also required a skilled water tender to avoid damage to the boiler. Nonetheless it was the remarkable performance of the Herreshoff built boats equipped with the coil boiler and engines designed by Nathanael that was responsible for the early reputation and success of John's steamers and later those of the Herreshoff manufacturing Co,. A strong case can be made that if it had not been for the coil boiler the Herreshoff Manufacturing Company as we know it would not have come into existence.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[75] Letterbook, Series 1Sub Series B , Box 1 Folder 3, George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University

[72] Capt. Nat Herreshoff: The Wizard of Bristol, Pg. 94.

[76] Rhode Island History magazine January 1946, Pg 6-9.

In what manner did the Corliss Steam Engine Company benefit from Nathanael's eight plus years with the company ?

The short answer is a great deal.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

Nathanael was the first formally educated engineer to be employed by the Corliss Steam Engine Co. While both George Corliss and Edwin Reynolds were highly skilled, successful and experienced inventors with considerable machinery and manufacturing knowledge neither had the mathematical skills or formal scientific training Nathanael possessed when he joined Corliss.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

The fact Edwin Reynolds, soon after Nathanael was employed, took him to assist with indicating customer's engines indicates Nathanael's capabilities were quickly recognized. Nathanael's early assignment to completely assume this important responsibility and his reputation in the shops as the “engine doctor” indicate he became a well known and respected employee. Nathanael's MIT education and his experience with the inefficient and noisy Hope Station pumping engine enabled him to understand the great advantages of the higher pressure, compound, steam jacketed pumping engines he observed during his 1874 trip to Europe. This knowledge, together with his education and mathematical skills, permitted him to perform accurate tests of the first Corliss experimental pump and numerically document the results in a manner that convinced Mr Corliss to abandon his complicated radial engine designs. Mr. Corliss may not have had an engineering education or understood the thermodynamics of steam but he was a very good businessman and understood numbers. Nathanael's understanding of the advantages of the compound engines that he gained during his time in Europe enabled him to convince Mr, Corliss to incorporate those features in the second experimental engine built in 1875. Nathanael contributed significantly to the design of the second experimental engine and later the notable Pawtucket pumping engine both of which were compound engines with steam jacketed cylinders. These machines and the later similar Pettaconsett pumping engine rescued the Corliss Company's pumping engine reputation.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

The number and length of “leaves of absence” Nathanael was granted for various reasons is certainly an indication he was someone the Corliss Co. valued highly and certainly desired to retain.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

In Nathanael's response to the National Cyclopedia of American Biography he states he had assigned some patents over to the Corliss Steam Engine Co. One of them was certainly #177099 Nathanael's vacuum dash pot invention and I believe the other was #177059 the simplified valve linkage, both dated 1876. The “Corliss Tongs” are an illustration of the many smaller but undocumented improvements and innovations he likely contributed.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

The assignment to participate in the design of the Centennial Engine and then on short notice step in and start it up at the opening of the 1876 Exhibition is certainly evidence of the confidence George Corliss had in Nathanael's capabilities. One documented indication that he was missed after he resigned is a letter from the Corliss Co. dated April 1878, inquiring if Nathanael could indicate a customers engine. Nathanael replied he was unable to do so as he was very busy with the gunboat [Clara #39]. The Corliss Company wrote back saying they understood.[77]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[77] Herreshoff Marine Museum Curators Log, April 2019, Herreshoff Biographies of 1904 Part 1

Nathanael's own brief summary was; I was able to be of great assistance in improving for Corliss his entire gear and particularly the vacuum dash pot which became standard after 1876”[3]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[3] Attachments “A” and “B” Herreshoff Marine Museum, Curator’s Log The Herreshoff Biographies Part four, by John Palmieri

This was certainly not an apprenticeship as has sometimes been written.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

How did Nathanael's career at Corliss influence and benefit the Herreshoff Manufacturing Co. (HMCo,) ?

Significantly.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

The Corliss Steam Engine Co., located in Providence Rhode Island, was the perfect opportunity for a person of Nathanael's education, youthful machine tool experience and well developed interest in steam engineering. In addition, Providence was well known to Nathanael and had convenient rail service to Bristol which permitted convenient visits with and from his large family.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

When Nathanael began work at Corliss in 1869 the company was at it's zenith as a well established very successful heavy equipment manufacturing plant. The Corliss works possessed all the shops, skills, and associated machinery required to build their engines and boilers. In addition the Corliss works designed and built their own production equipment. They had, at the time, the largest pit lath in the country which permitted them on short notice to machine the bearing ring for the U.S.S. Monitor. Their twenty three foot long planner remained in operation at a west coast shipyard until after 1945.[78] In modern parlance it was a first class vertically integrated manufacturing facility renowned for the quality of it's products. The pattern shop, foundry, forge shop, machine shop, boiler shop and assembly area, all presented Nathanael a unique opportunity to observe first hand the skills, logistics and organization required to successfully manufacture large complex equipment and supervise a large work force. In Nathanael's own words“It was a fine schooling for me in steam engineering matters”[10]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[78] Adapted from Professor Stephen Ressler Ph.D, U.S.M.A West Point, New York

[10] Mystic Seaport Museum GW Blunt White LibraryLFH Collection 138 Box 16 Folder 13; 23 of 24

The two weeks Nathanael spent at the Centennial Exposition in 1876 was certainly a unique opportunity afforded to very few individuals and provided an opportunity to observe in operation the best machinery from many parts of the world. This had to have been not only very technically informative but a very significant cultural experience as well.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

The organization and operation of the Herreshoff Manufacturing Co. resembled in many ways that of the Corliss Steam Engine Co.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

- • There was a foreman in charge of each shop.

- • Both companies were known to hire the best available men, particularly the foremen.

- • Both companies paid their men an above average wage.

- • Both companies were known for the quality of their products.

- • Both companies asked and received top dollar for their products.

- • Both companies occasionally manufactured products other than what they were most noted for.

- • Both companies began construction / manufacture only upon the placement of an order and most orders were to varying degrees custom products.

- • Both companies were for a period of time run by a team of two brothers, one the inventor and the other an administrator.

- • Both companies were privately owned.

- • Both companies gained an international reputation for their products performance and quality.

- • Both companies were vertically integrated organizations.

- • Both designed and manufactured in their own shops nearly every element of their finished product. This structure provides superior cost, quality and schedule control.

- • Neither company ever had a work stoppage due to labor issues.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

George Corliss and Nathanael Herreshoff shared many traits.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

- Both men were workaholics dedicated to their company and profession.

- Both were very creative individuals.

- Both NGH and George Corliss toured their shops each day and had the final say in all decisions.

- Both expected and received an honest days work from their employees.

- Both men demanded quality work.

- Both men designed their own production facilities and special machinery.

- Both men had the confidence to start a new company, with a partner, at an early age. George Corliss at age 31 and Nathanael just shy of age 30

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

George Corliss and Nathanael were however quite different in many other respects.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

- Unlike Nathanael, Mr. Corliss was a very public person who sought the limelight and honors.

- Mr Corliss was very involved with politics and his church. Nathanael was not.

- Mr. Corliss applied for and vigorously defended many patents Nathanael patented very few of his inventions. I am not aware of Nathanael defending any patent infringements.

- Nathanael was first and foremost a very talented engineer who by self study kept up with the advancement of technology and materials. Mr Corliss, was a very inventive smart business man, who with the aid of others made incremental improvements to his basic invention.

- Nathanael with his natural talent, education and applied mathematical skills was a far more versatile and technically progressive individual than George Corliss.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

Conclusion;

Nathanael always considered himself an engineer.[79] What exactly is an engineer?

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[79] Mystic Seaport Museum L. Francis Herreshoff Collection138, Box 17, Folder 11.

An engineer is an individual who employs mathematics, science and technology to create a system, component or process to accomplish a specific function.[80]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[80] An Industrial Heritage, Allis Chalmers Corporation, Walter F. Peterson Pg. 440, index.

Mathematics is a constant, science advances slowly and technology is ever changing. Thus engineering, if it employs the latest technology, is an iterative discipline. No one better fits this definition of an engineer than Nathanael Greene Herreshoff.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

Nathanael's interest and ability to remain abreast of advancing technology enabled him to investigate and utilize the latest materials and unlike many others change with the times. In a January 1935 letter to his son L. Francis he wrote “My early ambition was to in direction of Steam Engineering, and I followed that line until I was convinced internal - combustion engines were better and would finally absorb the field.”[81]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[81] "Life Work of Centennial Engine," S. H. Viall Power 42, July 13, 1915.

Nathanael's command and use of mathematics was extensive but has seldom been acknowledged to the degree it deserves. His capacity to mathematically develop designs and solve design problems provided the confidence necessary to safely introduce new materials and ideas. The only published acknowledgment of Nathanael's mathematical abilities that I discovered is within the January 1925 edition of the MIT Review. This article credited him with “unusual powers of applied mathematics” it later went on to say“when he joined his brother he immediately set his mathematical genius to the problems of marine engineering.” Nathanael's life long commitment to self improvement permitted him to stay abreast of developments in technology and his education in mathematics and science at MIT provided the foundations of a remarkable engineering career.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

The rest is well known, Lighter, Stronger, Faster.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

EPILOGUE

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

Edwin Reynolds

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

In July of 1877 Edwin Reynolds joined the Reliance Works of the E.P. Allis Company in Milwaukee, Wisconsin as General Manager and Superintendent at a yearly salary of $3500 a significant reduction from his $5000 Corliss salary. Although E.P. Allis, was at time, a small struggling company Reynolds saw an opportunity as Mr. Allis wanted to develop and expand his steam engine business. Mr. Allis always attempted to hire the best people he and gave his managers freedom to run their divisions as they saw best. In addition he permitted his employees to retain the rights to any patents issued to them.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

That Reynolds succeeded is an understatement as by the mid 1880's the Reliance Works had superseded Corliss as the most important steam engine builder in the country. Reynolds rapidly developed the higher speed and more powerful engines required by a modernizing industrial base. He was noted for his very large pumping engines for municipalities and air blowing engines for blast furnaces. Reynolds was also the first to successfully shaft mount the electric generator in place of the engines flywheel thus eliminating the cost and inefficiency of belts or gears. As an encore to the 1876 Centennial, Reynolds built a 3000 hp quadruple expansion engine for the Colombian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. The engine had a 30 ft. dia. flywheel and powered two 750 kilowatt Westinghouse generators. The engine was first started by President Grover Cleveland and was known as “The pride of Machinery Hall”. The largest Reynolds engines were a series of nine 12,000 hp engines to provide electric power for the New York City transit system. Some of these engines ran for more than 50 years being scrapped about 1960.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

In 1901 Reynolds orchestrated the merger of E.P. Allis and Chicago-based Fraser-Chalmers Company, Gates Iron Works and the Dickson Manufacturing Company to form the Allis-Chalmers Corporation and became Vice President of the new corporation. He also served a term as president of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers 1902-1903.[82]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

George G. Phillips

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

George Phillips became a lifelong friend of Nathanael's and in 1880 after 14 years at Corliss he went to work at the Herreshoff Manufacturing Co. About 1884 he accepted a job offer from Edwin Reynolds at E. P. Allis Company in Milwaukee.[20] Following his retirement from Allis Chalmers in 1902 he returned to Rhode Island and purchased the Roaring Brook Farm in the village of Hopkins Hollow in Coventry Rhode Island. He became active in politics and served in the State Legislature in 1908-1909. During the time he worked in Milwaukee the Phillips visited Nathanael summers and they frequently exchanged visits following the Phillips return to Rhode Island.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[20] "The Log of the Riviera." Within; Recollections and Other Writings by Nathanael G. Herreshoff. Bristol, 1998, Pinheiro, Carlton J. (ed).

The Centennial Engine

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

Upon the close of the Centennial Exhibition in November 1876 the engine and shafting were disassembled and shipped back to Providence Rhode Island. In 1880 the engine shafting and gears were sold to George Pullman to power his railcar manufacturing shops in Pullman Illinois. 35 railcars were required to transport the engine and shafting from Providence, R.I. to Pullman, IL. The engine was then set up in a specially constructed engine house and started, again with great ceremony, on April 5, 1881. When at Pullman it regularly produced 1460 hp at 43 pounds steam pressure and a maximum of 2520 hp at 75 pressure. It was not however run long at the higher power as it experienced high wear and excessive oil consumption at that loading. The engine remained in service for 29 years until the Pullman shops were electrified in the fall of 1910.[83]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

Corliss Steam Engine Co.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

George Corliss did not keep up with the changing requirements of his costumers and fell behind the competition. George Corliss died in 1888, the company was reorganized in 1894 and taken over by International Power Co. in 1899. A short history of the Corliss Steam engine Co. written by George Phillips appeared in the December 4, 1902 issue of Iron Age magazine in which he began “I have always reckoned it as one of the pieces of good fortune that has come to me in my life to be connected in business relations with a man like Mr. Corliss. In the 14 years that I was in his employ as mechanical draftsman I came to know him well.”

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

Toward the end of the article Phillips reflects on Edwin Reynolds departure from Corliss. “To one who grew up in the old shop and has always taken a lively interest in it's welfare it is pitiful; and the reflection forces itself on one that if the broad gauged practical man who went out from it 25 years ago to build engines in Milwaukee had remained to direct it's affairs the greatest steam engine works in this country, if not the world, would not have been as they are on the shores of lake Michigan but in the city of Providence.”[14]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[14] Iron Age magazine, December 4, 1902, Pg. 36d.

[1] Nathanael's Greene Herreshoff 1848-1938 Wadsworth Atheneum Marine Room, Publication Number 2, Pg. 15.

[2] MIT Museum Exhibit “Lighter, Stronger, Faster; The Herreshoff Legacy,” 2018-2019.

[3] Attachments “A” and “B” Herreshoff Marine Museum, Curator’s Log The Herreshoff Biographies Part four, by John Palmieri

[4] A general Purpose Technology At Work, The Corliss Steam Engine In The late 19th Century, Nathan Rosenberg, Pg 24.

[5] Rhode Island History Magazine, January 1946, Pg. 5,6,7,8.

[6] A general Purpose Technology At Work, The Corliss Steam Engine In The late 19th Century, Nathan Rosenberg, Pg.14.

[7] A general Purpose Technology At Work, The Corliss Steam Engine In The late 19th Century, Nathan Rosenberg. Pg 10,11.

[8] MIT Presidents Annual Report 1895 MIT Archives.org, Pg 22.

[9] MIT Presidents Annual Report 1895 MIT Archives.org, Pg. 8-9.

[10] Mystic Seaport Museum GW Blunt White LibraryLFH Collection 138 Box 16 Folder 13; 23 of 24

[11] An Industrial Heritage, Allis Chalmers Corporation, Walter F. Peterson, Pg.41.

[12] Series 5, Box 3, Folder 12.1-12.16K George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University the Transcribed interview of NGH by George Hall, W.E. Richardson 12/2/1932

[13] Series 5, Box 3, Folder 12.1-12.16K George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University Transcribed interview of NGH by George Hall, W.E. Richardson 3/18/33

[14] Iron Age magazine, December 4, 1902, Pg. 36d.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Folder Subject: Article in 'Power' on George Corliss. HMM Subject Files, Folder 53 (new), 209 (old) 1923-04-08.

[17] National Engineer magazine March 1903, Pg 5.

[18] Recollections and Other Writings by Nathanael G. Herreshoff. Ed. Carlton J. Pinheiro, Pg 24.

[19] Series 5, Box 3, Folder 12.1-12.16K George Corliss Coll. Hay Library, Brown University Transcribed interviews of NGH by George Hall, W.E. Richardson 12/2/1932.

[20] "The Log of the Riviera." Within; Recollections and Other Writings by Nathanael G. Herreshoff. Bristol, 1998, Pinheiro, Carlton J. (ed).

[21] Boat Builders of Bristol, Samuel Carter III, Pg. 48