August 18, 2021

The Herreshoff Brothers and their Torpedo Boats, Part IV: Preparing for a STILETTO

A series of papers on bringing innovation to the "New Navy"

by John Palmieri

See on-line THE HERRESHOFF CATALOGUE RAISONNÉ for detailed information on HMCo. # vessels including photos, half model images and descriptive documents

Introduction

STILETTO was born out of the quest for torpedo warfare technological parity with Europe that engaged both Herreshoff and the US Navy- each for their own purposes and in their own way.

There was much to be done before the Herreshoff brothers were prepared to design and build a STILETTO and before the US Navy had the Congressionally supported institutional plans to develop the need for such a high-speed vessel. Those preparations are the subject of Part 4.

For the Herreshoff Brothers this meant building upon the widely publicized successes of VISION and LIGHTNING by-

• Leveraging the increased orders they fostered to establish the Herreshoff Manufacturing Co. (HMCo) structured upon a continuing set of business principles.

• Testing their latest designs in Europe, while simultaneously assessing by examination the latest English steam and torpedo boat technology.

• Obtaining and applying Froude’s latest model testing theories in an unprecedented experimental model test program influencing HMCo steam vessel hull designs for the next 10 years.

• Continuing development of their boiler and engine designs supporting an aggressive marketing strategy for civilian yachts and launches as well as specific segments of US Navy torpedo boats and their machinery.

For the US Navy this meant

• Reversing 15 years of zero technology development, save for the little done by the Torpedo Corps at the Newport Torpedo Station, by creating a credible (in the view of Congress) naval advisory system to develop the plans for a modern steel navy; where torpedo boats and automobile torpedoes were a small, but technically advanced segment pushed hard by Admiral Porter and the Torpedo Corps.

• Supporting the process by fostering the development of a domestic steel industry and conducting individual European naval assessments and the purchase of ship and machinery designs.

These efforts took place during a time of significant change in shipbuilding, and we start our story with as overview of that time and where the leading torpedo boat builders including Herreshoff fit in the shipbuilding universe.

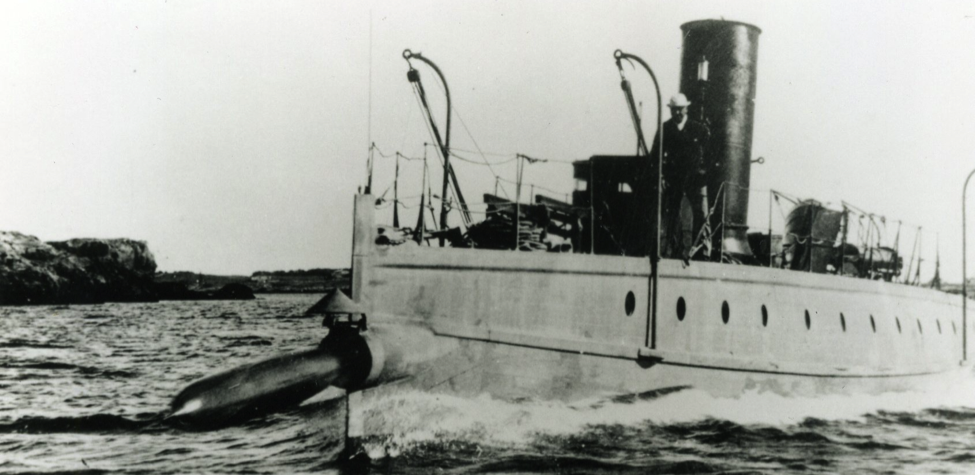

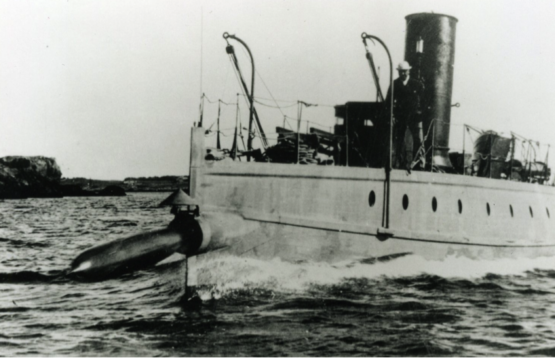

Figure 1- The 94-foot STILETTO (WTB-1)- the 118th steam vessel built by the Herreshoff Manufacturing Co. as converted for torpedo boat service. Launching a Howell automobile torpedo from the bow tube c. 1890. (US Navy Photo)

Background- Shipbuilding 1880-1900[1]

The HMCo was founded during a transformative 20-year period where marine technology changed from design by “rule of thumb” accomplished by draftsman possessing only drawing skills, to a systematic, scientific design approach requiring trained engineers. Pushing this change were customers with “increasingly prescriptive” contracts and specifications including performance guarantees. At the same time small family-owned shipyards were being replaced by larger vertically integrated businesses directed by professional managers where products were built through standardized processes.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[1] Stewart A. McKenna & Larrie D. Ferreiro, “The Scientific and Management Revolution and Shipbuilding on the ‘Two Clydes’ 1880-1900.” Nautical Research Journal Vol.58, No. 2 Summer 2013. Pages 105-128. All information about the shipyards on the Clyde and the Delaware, their technology, and dates of the technology are taken from this research paper.

Leading the transformation were the large shipyards on the River Clyde in Scotland (William Denny, J & G Thomson and Robert Napier & Sons) followed by those in the Philadelphia region of the Delaware River. The Delaware River shipyards “were a distant second place” to the Clyde because-

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

1. The overall American industrial revolution was behind that of Britain.

2. The abundant American wood supply delayed the transition to iron and steel hulls.

3. In Britain scientifically based naval architecture was fostered by the establishment of the Institution of Naval Architects (INA) (today the RINA) in 1860 and the opening of the first school of naval architecture and marine engineering in 1864. While in America the American Society of Naval Engineers (ASNE) was not founded until 1888 by steam engineers in the Bureau of Steam Engineering (BuSteam) followed by the larger Society of Naval Architects & Marine Engineers (SNAME) in 1893 (with Nat Herreshoff as one of the 22 members of the governing Council).[2] American education in naval architecture and marine engineering did not start until 1894.

[2] William duBarry Thomas. “The Genesis of a Professional Society”. SNAME Transactions. Vol.101, 1993, pgs.31-9.

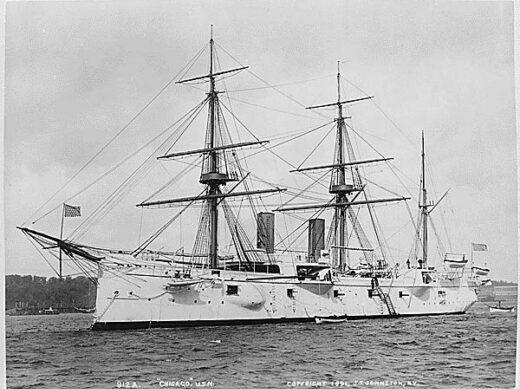

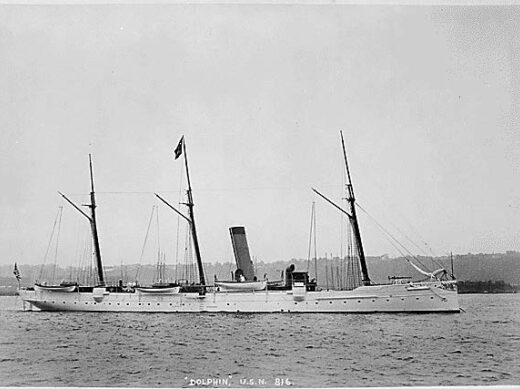

The leading Delaware River shipyards were William Cramp & Sons founded in 1825, Harlan and Hollingsworth founded in 1837 and John Roach & Sons founded in 1864. In 1870 John Roach toured the Clyde yards to understand their techniques and organization. Returning home he changed his yard to a vertically integrated plant, adding the production of steel plate, frames, boilers, and piping, and increasing its staff by 50% to 1500 employees. Aided by the US Navy’s transfer of British technology in the form of detail drawings of cruisers and compound steam engines, Roach in 1883 won contracts for the first ships of the New American Steel Navy- known as the ABCD ships. (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

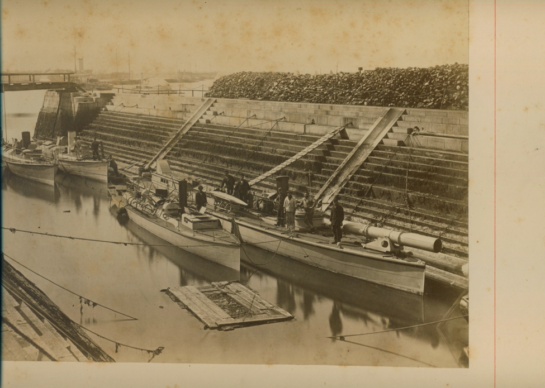

Below the large shipyards but no less advanced were the developing Herreshoff Manufacturing Co. (HMCo) in America, Thornycroft and Yarrow, the two leading British torpedo boat builders located on the river Thames, and Normand in Le Havre, France. (Figure 4). The British publication IRON, summarized in 1883, “The torpedo-boats of Thorneycroft and Yarrow in England, and of Herreshoff in the-United States, illustrate the most successful practice of today, and their attainment of speeds exceeding twenty miles an hour may be accepted as the most remarkable triumphs of recent mechanical engineering.”[3] (Not out of character for the Brits not to recognize the French Company Normand.) All were vertically integrated, designing and manufacturing their own boilers and engines. Thornycroft, Yarrow and Normand were active in the Transactions of the INA; Thornycroft and Yarrow both engaged in experimental and theoretical studies of ship resistance.[4]

Herreshoff we will explore in more detail. Suffice it to say for now that while family managed, Herreshoff engineered its products in a “systematic, scientific approach” at the direction of an educated and well-experienced engineer, excelled at manufacturing standards/process improvement, and was vertically integrated because of the brothers’ decision to build everything that they designed.

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[3] “Marine Engineering”, IRON, London, Jan. 19, 1883. Pg. 55.

[4] For example, John L. Thornycroft, “On the Resistance Opposed by Water to the Motion of Vessels of Various Forms and the Way in Which This Varies with the Velocity”, Transactions, INA Vol. 10, 1869. William Yarrow, “Some Experiments to Test the Resistance of a First Class Torpedo Boat”, Transactions, INA Vol. 24,1883. A copy of the Yarrow paper was available to George Converse and is in his archives Series 1, Box 1, Folder 16, George Albert Converse Papers and Photographs (MSS 0068x), DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University.

Torpedo boats required the most detail engineering and economy of material of any type of warship, save for maybe the submarine. Light hulls were highly stressed. Fittings and machinery were of the lightest weight and compact design. Use of the water tube boiler (a Herreshoff innovation see later comments by Nathaniel Barnaby former Director of Naval Construction, British Admiralty) and high RPM triple/quadruple expansion engines drove machinery weight to as low as 50 lbs./ihp vs. 200-300 lbs./ihp for the best large contemporary warships.[5]

[5] Edgar C. Smith, A Short History of Naval and Marine Engineering, (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK, 1938). Chap. XVII “Machinery of Torpedo Craft”, pp 254- 270

Thornycroft, Yarrow and Normand were the same age as John Brown Herreshoff. John Thornycroft started building steamboats in 1866 at age 23, Alfred Yarrow started at the same time. Normand, from a shipbuilding family, took over the family firm in 1871. Nat may have visited the Thornycroft Cheswick (Chiswick) yard during his 1874 cruise in RIVIERA.[6] The three had a friendly rivalry, writing and commenting upon each other’s technical papers. They were well supported by their governments. Early on the Admiralty had decided to depend fully on private industry for the design and construction of its torpedo boats and their machinery. They also encouraged the design and construction of torpedo boats for foreign navies as well as the foreign sale of drawings- including to the US Navy. The French Navy had similar policies.

[6] Carlton J. Pinheiro Editor, Recollections and Other Writings by Nathanael G. Herreshoff, “The Log of the RIVIERA.” & NGH “Notes from Memory March,1932.” (Herreshoff Marine Museum, Bristol, RI, 1998) Pages 81-92. Nat writes that one day they cruised the Thames to a little beyond Cheswick (Chiswick). Chiswick was the site of the Thornycroft yard, but he does not mention the yard. In view of Nat’s intense interest in ships, shipbuilding, and self-study it is believed that he visited several shipyards on RIVIERA’s 1874 cruise, but the only one he mentions is the shipyard and machine shops of the Maritime Company; “largest thing of the sort in France” where he saw large boiler and engine works. Pg. 85.

At about the time Herreshoff was building the one-offs STILETTO and CUSHING with a workforce 100-200, both Thornycroft and Yarrow employed 1000-1200 men and were building tens of torpedo boats per year.[7]

[7] “Modern Torpedo Boats.” Reprint from Scribner Magazine. Newport Mercury, April 9, 1887.

Founding the Herreshoff Manufacturing Company (HMCo)

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

As 1877 dawned, the 36-year-old John Brown Herreshoff, supported by Nat’s design talents, had been directing the building of boats, marketing and negotiating their sales for 14 years, both on his own and in partnership, exhibiting an “invincible determination and persistence” for success.[8] The catalysts for the next step, the creation of a lasting partnership in the form of the HMCo, were the expansion of the business brought on by the success of the coil boiler, mother Julia’s desire for Nat to work with and support John as he had since the age of eight, and most importantly Nat’s development as an engineer.

[8] Orison Swett Marden. How They Succeeded: Life Stories of Successful Men Told by Themselves. (Boston: Lothrop Publishing Co., 1901) “Chapter XVII John B. Herreshoff, The Yacht Builder”. Pages 280-1; 287-8. (Other business leaders featured include Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller, further evidence of John’s stature in American business.)

For a full understanding of Nat Herreshoff’s development as an engineer and the person he had become by 1877 the reader is referred to Jim Giblin’s, “Nathaniel Greene Herreshoff Steam Engineer: the Corliss Years”, Herreshoff Marine Museum Code Flag Lima #63. In this well researched paper Jim answers the important questions as to how Nat’s MIT education as a mechanical engineer, his European trip of 1874, and career at the Corliss Steam Engine Company developed him as a steam engineer and prepared him to be the designer and superintendent of the works of the HMCo. Nothing can be more important to understanding Nat Herreshoff, for as he himself wrote in his draft autobiography he was first a “marine engineer” and then a “yacht designer”.[9]

[9] In 1926 Nat Herreshoff was provided six Herreshoff biographies from the 1904 volume of The National Cyclopedia of American Biography. From 1926 into the early 1930s. Nat undertook to correct and add to the published biographies of himself and his two older brothers, James and John. The drafts of his biographies can be found in one small folder of Mystic Seaport’s L. Francis Herreshoff Collection 138- Box 16, Folder 13. The papers are very important to a better understanding of how Captain Nat viewed both his life and career, and the part his two brothers played in the founding and shaping of the Herreshoff Manufacturing Company. They were analyzed in a 2019-20 four-part Curator’s Log series, “Captain Nat and the Herreshoff Biographies”. In addition to addressing “Product Lines” his draft autobiography;

Characterization- identifies himself as a “marine engineer and yacht designer” rather than the Cyclopedia’s “boat builder and designer”.

Success- Nat describes success at every stage of his life; boatbuilding and sail racing as a youth, steam engineering at MIT and Corliss, and designing and superintending at HMCo.

Defense of 1901 America’s Cup Contender CONSTITUTION- Capt. Nat was forever sensitive about the criticism he received when his new CONSTITUTION lost in the defender trials to his 1899 boat COLUMBIA.

Credits & Family- Credits his forefathers for his early love of the sea and vessels; blind brother John for introduction to boats and mechanical things at an unusually young age; for steam engineering, opportunities offered by Mr. Corliss; brother John for their “successful and well-known business”; Commodore Edwin Morgan for his part in HMCo’s “world-wide reputation” in sailing yachts.

A “marine engineer” of the time encompassed both mechanical engineering and steam engineering. For me, Benjamin Isherwood was the most accurate in characterizing Nat Herreshoff. On COLUMBIA’s 1899 Americas Cup win he wrote to Nat, “The real great men of a country are its great Engineers and Constructors, and you stand at the head of both professions.”[10]

[10] Benjamin F. Isherwood letter to Nathaniel G. Herreshoff, October 21, 1899. Nathanael G. Herreshoff Collection. Herreshoff Marie Museum. Access courtesy Halsey C. Herreshoff. (It is interesting that Isherwood always wrote “Nathaniel” with the “ie”, rather than the “ae” used by Nat in his adult years.)

The “Brother’s Agreement” of founding principles for the HMCo with John as President and Treasurer, and Nat, at first as Designer, and shortly both Designer and Superintendent of the Works, is simply stated as follows-

- • Borrow no money – John was to pay off debts accumulated in the lean years before the coil boiler. Going forward, there was to be no borrowing, rather prudent investment of profits into the business.

- • Best workers & material – No compromise to the elements that assure quality products.

- • Build only to our designs – A commitment to design superiority and continuing improvement.

- • Sell our designs to no one – The Herreshoff name has meaning. It is a guarantee of design and manufacture excellence..

- • Products advertise themselves – We are committed to excellence; every day, in everything we produce. Product performance, not words, underwrite our guarantees.

- • Contract only with those willing to pay the price – We sell and compete on performance.

It was an optimistic and aggressive posture. Optimistic-- they believed that in any field they entered they could both develop competitive designs and manufacture them at a profit. Aggressive- in every field they entered they meant to compete at the top level.

The plan in practice was this- tell us what you want it to do, but not how. We will design and build it for you, and we will guarantee its performance. A good example is William Randolph Hearst. He wanted the fastest boat on the West Coast. It was agreed that 25 knots would do it. So Herreshoff designed and built the 112-ft. VAMOOSE (HMCo #168) to do 25 knots. The contract stipulated that Hearst would not accept delivery if it failed to meet that speed. It did and delivery was accepted.[11]

[11] VAMOOSE never made it to the West Coast. The President of the railway across the Isthmus of Panama refused to transport VAMOOSE because of an article Hearst’s newspaper had written slandering the President’s daughter. See “William Randolph Hearst, The Herreshoffs and the Yacht VAMOOSE: Parts 1 and 2”, Curator Log 2012. Herreshoff Marine Museum.

Nat was justly proud of the company’s results in the high-performance sector of the steam market, noting in his 1930s draft biography in a non-bragging, matter of fact manner, “in no case did either the yachts or torpedo boats fall short of contract requirements as to speed or general conditions.”[12] [13]

[12] Draft of Nat Herreshoff’s autobiography Mystic Seaport, L. Francis Herreshoff Collection 138- Box 16, Folder 13.

[13] N. G. Herreshoff letter to L. F. Herreshoff, October 29, 1935. Mystic Seaport L. Francis. Herreshoff Collection 138 Box 17, Folder 11.

At the founding of the expanding company there was much to be done. In addition to designing the new vessels, continually improving upon, and standardizing the designs of the coil boiler, steam engines, and all manner of vessel and machinery fittings, Nat was responsible for the factory expansion including design of new buildings, marine railways and docks as well as designing or selecting the shop machinery.

Nat Herreshoff the Engineer

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

L. Francis had a keen understanding of Nat’s work and habits. In a 1935 letter he offered insights to help paint a “word picture” of his father- [14]

[40] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. Washington GPO 1881 Pgs. 3, 5, 6.

[14] L. Francis Herreshoff ltr. to Uffa Fox of Oct. 22, 1935, pages 3-6, responding to Uffa Fox ltr. of Oct. 5, 1935. Mystic Seaport L. Francis is Herreshoff Collection 138. Box 1, Folder 5. LFH provided comments about his father in response to Uffa’s desire to create a “word picture” of Nat Herreshoff.

- • Nat “kept his eye on the ball” and devoted “many hours each day to his work… started very early (several hours before breakfast) and continued until three or more hours after supper.”

- • He “undoubtedly modeled more boats than any other man. He also probably designed more models and sizes of steam engines than any one man.”

- • He had an advantage over other designers whose products were built in different yards since all of his work was done in the HMCo shops with which he was completely familiar and therefore able to keep the work at a high standard and true to the design.

- • He was “relieved from much business and financial worry by his brother John.”

- • “Like any one who beats others in their profession, (he) did a great deal of original thinking. He developed his own formulas and made his own tests of material, etc. He had the ability to make simple tests which showed the truth so that his mathematical calculations were based on something definite.”

Over his career Nat was responsible for several significant developments/accomplishments documented in listings as follows-

[40] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. Washington GPO 1881 Pgs. 3, 5, 6.

- • “Developments of Nathanael G. Herreshoff” by his son A. Griswold Herreshoff, Herreshoff Marine Museum Chronicle Spring 1981. Page 2. This listing of 32 “Developments” is the most extensive of the three.

- • “Some of Captain Nat’s Accomplishments” Captain Nat: The Wizard of Bristol, Chap. 15. By L. Francis Herreshoff (Sheridan House, New York) 1953. Pages 323-4. A 15-item list of “Accomplishments”.

- • A listing of 9 items that Nat “developed to a useful state”, which L. Francis Herreshoff provided to English boat designer Uffa Fox in 1935. [15] (Click Here to view Attachment A). This list is of interest because there is a record of Nat’s comments about the list.[16]

- ◦ #1 – The light steam engine; and first fast steam torpedo boats. Nat responds- “#1 light steam engine I cannot claim to be first for I was after Thornycroft.” Nat knew this because he had followed Thornycroft’s work in the Institution of Naval Architects (INA) Proceedings and had himself inspected Thornycroft’s HMS LIGHTNING in 1879.

- ◦ #2 – Nearly all of the methods of constructing light wooden hulls we use today. Nat responds- “#2, - Light construction This interesting study began in earnest in 1874”. That is “light construction” began with VISION’s hull carrying the coil boiler and associated light steam machinery and as a “study” it continued throughout his career for both wood and metal hulls. It was a continuing process and achievement. It is no wonder that Nat took great offense when in 1897 the Navy Bureau of Construction & Repair (BuC&R) declared PORTER (TB-6) a “lesser product” partly because it was lighter weight than the Bureau design. It was lighter because Nat engineered it that way without compromise of hull strength.

New Features in version 2.3

With the newest version of our product, you can now set calendar alerts, add images to your events and send notifications on your phone.

Attachment A

Nat Herreshoff developed to a useful state the following-

- • The light steam engine; and first fast steam torpedo boats.

- • Nearly all of the methods of constructing light wooden hulls we use today.

- • The web frame and longitudinal construction for metal hulls, afterward patented by and known as the Isherwood system.

- • The streamline shaped bulb and fin keels.

- • The cross cut sail with the cloth running at right angles to leech.

- • Light hollow steals spars, combined with scientific rigging.

- • The flat stern form of steam yachts, capable of being driven at high speed length ratios.

- • The development of overhangs on sailing yacht to allow longer lines and greater stability.

- • The sail track and slide in its present form, and a great many patterns of marine hardware in common use today.”

Source-L. Francis Herreshoff ltr. to Uffa Fox of Oct. 22, 1935, pages 1-2, responding to Uffa Fox ltr. of Oct. 5, 1935. Mystic Seaport L. Francis is Herreshoff Collection 138. Box 1, Folder 5.

[15] Ibid, pages 1 & 2.

[16] NGH letter to LFH, October 29, 1935. Mystic Seaport L. Francis. Herreshoff Collection 138 Box 17, Folder 11.

The Developing Herreshoff Manufacturing Company (HMCo)

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

In April 1878 father, Charles F. Herreshoff, led a reporter on a tour of the company, then employing 70 skilled craftsmen, and consisting of three main buildings, plus the lengthened 100 feet Old Tannery, a waterfront building yard and wharf. Expansion was evident everywhere. The blacksmith shop featured a new steam trip hammer, the machine shop was fitting up coil boilers and building steam engines. The two-story main building featured a new pattern shop, a sheet iron and brass shop for engine and boiler casings, as well as a blast furnace for heating iron frames and a frame bending machine “of novel construction” invented by Nat. Vessels under construction numbered about eight including the 45-foot yacht PUCK (HMCo #38), a 60-foot shoal draft side wheeler, KITTATINNY (HMCo #41) for US Mail service on the upper Delaware river, and the 135-foot wl. gunboat CLARA (HMCo #39) for the Spanish Government. CLARA featured a composite wooden hull with Iron frames, large 8 ft. 3 in. x 12 ft. coil boiler and a vertical compound (double expansion) condensing 300 hp engine.[17]

[17] “The Herreshoff Manufacturing Co. Works”. Bristol Phoenix, April 13. 1878.

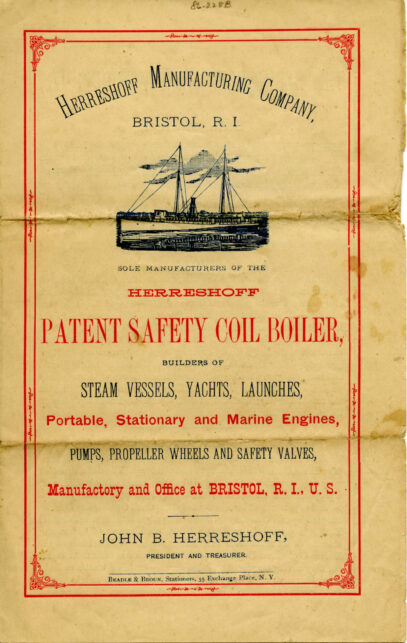

The article listed the company officials with John at the head, Nat responsible for “modeling and machine drafting”, carpenter Albert Almy superintendent of the shops, and Charles F. Herreshoff foreman of the wharf and yard. That Nat did not also start as Superintendent of the Works made sense because there was much design preparatory work and standards to be established to facilitate future production. Activities primarily related to boilers, engines, propellers, and steamers are documented in Nat’s Design Notebook No.1. from 1878 through the end of 1885.[18] (Table 1) In this we again see Nat’s analytical use of models in his design practice- in this instance modeling and test of engine valve gearing designs. The results of Nat’s work to establish standards work is evident in this HMCo 6-page sales brochure (Figure 5).

[18] Nathanael G. Herreshoff, Design Notebook No. 1. Nathaniel G. Herreshoff Collection, Herreshoff Marine Museum. Access courtesy Halsey C. Herreshoff. There are five such notebooks prepared chronologically covering the years 1878 to the spring 1934. Some are titled “Naval Architecture & Engineering Notes” and include Nat’s notes for individual vessel designs, design changes, shop reports of actual vessel weights, open-water model tests, various material tests, and design standards. Design Notebook No. 1. is unique- covering machinery, fittings and containing Nat’s personal listing of the construction record for steam vessels #1- #194. This listing is organized as the “HMCo Construction Record, Appendix C.” Guide to the Haffenreffer-Herreshoff Collection. Hart Nautical Collections, MIT Museum, 1997, except that there are some differences in the commentary.

Table 1: Summary NGH Design Activities 1878-1885- Design Notebook #1

ITEM | DATE |

|---|---|

Keel Condenser Design Table- 10 sizes with sketch | Undated |

Anchor Dimensional Table- 12 anchors from 10-110 lbs | Undated |

Engine Connecting Rod Dimensional Table- 23 conn rods with design curves for derivation | With directive for all conn rod configurations from Oct. 20, 1880 |

Fire brick Dimensional Table. Sizes A-Q | Undated |

Multi Tables- Scales of Sizes of Engines- Single-bed, Double-bed & Compound. Total 24 engines with dimensions. Boiler steam pressures 95-150 psi | Adapted Sept. 12, 1878 |

Single Coil Boiler- Dimensional Table Sizes A-Q | Undated |

Double Coil Boiler- Dimensional Table Sizes A-Q | Undated |

Screw Propellers- Both Medium & High. Pitch Dimensional Table. 20 sizes 14” to 120” Dia. for each pitch | Undated |

Screw Propellers- Table “Miscellaneous” 9 special designs | 1870-1878 |

Size of Shafting Dimensional Table- 24 sizes 15/16” – 6” dia. Both engine and screw shafts. | Undated |

Piston Packing Spring Dimensional Table- 21 sizes | Undated |

List of Steamers #1- #194 (See Endnote 16) | Undated |

Sizes of Bolt Threads; Dimensional Table- 5/16”- 3” dia. | Undated |

Stuffing Box Fine Threads & Sizes of Stuffing Boxes; Dimensional Tables | Undated |

Engine Valve Gearing Designs; Notes, design sketches, dimensions & data from model testing. About 15 designs. | Oct. 4, 1880 to Dec. 10, 1885 |

The facility expansion reported in April 1878 continued. In 1881 a new machine shop was expected to double the capacity for building engines, including sizes up to 1000 hp and to increase employment to 100 or 125.[19] In 1883 HMCo was for the first time among those paying more than $100 in property taxes with an assessed valuation of $30,000 and by 1884 it had increased to $56,500 where it remained for its torpedo boat building years through 1898.[20]

[19] “The Herreshoff Manufacturing Co.”, Boston Journal of Commerce, April 2, 1881.

[20] “Bristol Property Taxes”. Bristol Phoenix Aug. 11, 1883, and subsequent Bristol Phoenix annual property tax reports through 1898.

Spar Torpedo Boat HERRESHOFF (HMCo #44) 1878-79

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

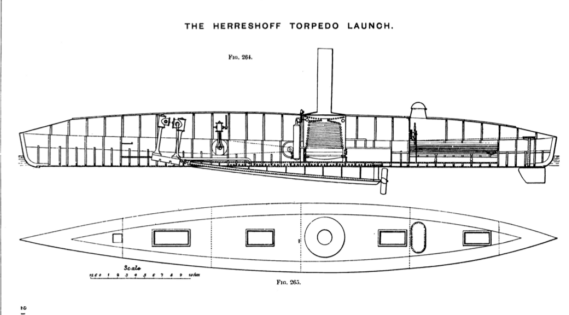

The success of LIGHTNING brought to Bristol several foreign orders for torpedo boats and also English mechanical engineer George R. Dunell. Impressed with the Herreshoff operation and designs, Dunell acquired British patent rights from John and James for Herreshoff designs related to torpedo boats including the coil boiler and was awarded in 1878 a British Admiralty contract for the 59-foot spar torpedo boat, HERRESHOFF (HMCo #44).[21] Dunell hoped this would be the first of many orders, but that was not to be, #44 was a one-off, save for two 48-foot videttes. The Admiralty, master of the most powerful navy in the world, had been steadily improving its steam launches and torpedo boats, but always in the same direction, steel hulls powered by locomotive type fire tube boilers, each building on a previous design from its primary builders Thornycroft, Yarrow and White. The Herreshoff boat, composite hull and coil type water tube boiler, represented “an improvement from a new point of departure” and they wanted to fully test one themselves.[22]

[21] Frederick J. Rowan A.M.I.C.E., M.I.E.S. The Practical Physics of the Modern Steam Boiler. (P. S. King & Son, London; D. Van Nostrand, New York, 1903). Pg. 481.

[22] The details of HMCo #44 are taken from (1) “Torpedo Boat Experiments” Irish Times, Jan. 10, 1879, page 3. (2) “The Herreshoff Torpedo Boats” Recent Practice in Marine Engineering Two Volumes. Edited by William Henry Maw. Publisher: London Offices of Engineering, London & J. Wiley & Sons New York 1884. Pages 280-6. This document is available online at www.hathitrust.org. All quotes about HMCo #44 are from this paper.

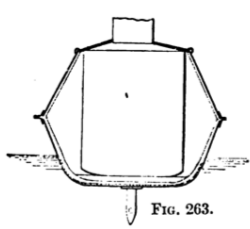

HMCo #44 (Admiralty designation TB 73) was a considerable improvement on LIGHTNING. The hull was of composite construction of steel frames with 7⁄8” white pine planking below the waterline and a 1⁄16” steel skin upper part, both joined to form a stiff box cross-section which together with a curved steel superstructure covering machinery and crew provided more than adequate strength for davit storage. (Figure 6)

[40] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. Washington GPO 1881 Pgs. 3, 5, 6.

Figure 6 HMCo #44 Hull Cross Section with outline of Coil Boiler, Vessel Profile & Plan Views.

Source- “The Herreshoff Torpedo Boats” Recent Practice in Marine Engineering. 1884. Pgs. 280-1.

Click images to view them larger.

HMCo #44 was very light, displacing only 6 tons in light condition with only permanent fixtures and 8 tons with torpedoes and stores.

[40] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. Washington GPO 1881 Pgs. 3, 5, 6.

The safety coil boiler was fabricated of 300 ft. of 2” dia. wrought iron pipe encasing the coal-fired combustion chamber. It was located within a closed compartment that could be pressurized to 1½ inches of water. Operating at pressures up to 160 psi the boiler provided steam to a compound engine developing 100 ihp. Located well forward, the engine drove through a curved shaft to a 38” dia. prop that was always in solid water. Whether going ahead or astern it could stop in ¾ boat length. The partly balanced rudder could turn 360° in any direction resulting in a tight turning circle of three times boat length.

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

There was great interest when John and Nat delivered HMCo #44 on Jan. 20, 1879, for its initial trials at the Royal Victualling Yard in Deptford on the Thames. Attending was the First Lord of the Admiralty and other senior staff. They witnessed the initial trials; davit hoisting tests with full crew and stores aboard, boiler steam up to lifting safeties in 5 minutes, rapid starting, stopping, turning and speed runs at the contract speed of 16 knots. All were highly successful. The Herreshoffs were complimented on the results. The boat was immediately accepted, and the bill paid.

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

After one week of trials #44 was delivered to Portsmouth where the Dockyard engineers took a more critical view of the vessel and the “difference between English and American ideas upon the construction of torpedo boat machinery soon became manifest…weaknesses remedied” in the design & construction of the engines, followed by orders from the Admiralty to “have her put through a searching trial.…the boat was run 4 hrs./day at full speed for 14 consecutive days, Sundays excepted…the most severe test that any torpedo boat had ever been put to… The boat passed through this test with perfect success.”

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

One concern was the special attentiveness required of the boiler tender to maintain proper feed flow and avoid either water carryover into the engine or coil tube failure from overheating. On one occasion while at Portsmouth the operators decided to try the “new fangled thing” themselves without notifying the contractor George Dunell, as they had been instructed. The upper part of the coil overheated “through defective circulation” causing a tube rupture. #44 went on to service in the Steam Reserve to instruct crews of the working of the Herreshoff system.[23]

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

[23] Nathaniel Barnaby, Knights Commander of the Bath, VP Institution of Naval Architects, Former Director of Naval Construction, British Admiralty, Naval Development in the Century. (Linscott Publishing Co. Philadelphia; W & R Chambers Limited, London, 1904) pp 127-129.

Nathaniel Barnaby, one time Vice President of the INA and former Director of Naval Construction, British Admiralty, noted a more significant impact of the trials of HMCo #44.[24]

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

[24] Ibid., page 129.

“Mr. Thornycroft and Mr. Yarrow noted that their performances in the corresponding 60 feet boats built of steel had been excelled in this roughly built but exceedingly clever and successful construction of wood and steel. Each of these engineers there upon designed a water-tube boiler as an improvement on that of Mr. Herreshoff.”

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

They both moved ahead rapidly with the development of the water tube boiler, writing about their designs in the INA Transactions and when facing boiler performance issues during the construction of USS CUSHING (TB-1) Nat Herreshoff adopted a Thornycroft three-drum design.

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

HMS LIGHTNING (TB 47) & the Torpedo Cruiser

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

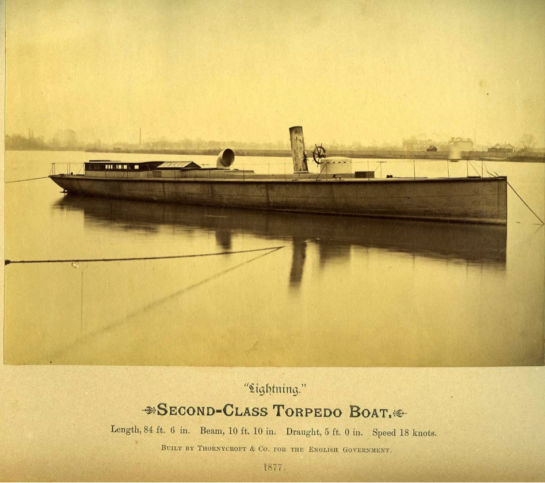

Before the London trials of HMCo #44 (trials with customers was John’s show) Nat went to Portsmouth to inspect HMS LIGHTNING (TB 47). Powered by a locomotive type boiler and compound engine she was ten times the displacement and seven times the HP of HMCo’s LIGHTNING. Designed and built by John Thornycroft, HMS LIGHTNING was used to test the new Whitehead automobile torpedo. The 1877 photo (Figure 7) shows HMS LIGHTNING as she was delivered in 1876 with torpedoes launched from each side by means of an on-deck “drop collar”. HMS LIGHTNING was later reconfigured with a forward mounted torpedo gun and on-deck storage for two torpedoes and that is how Nat found her when he went onboard at the Portsmouth Dockyard on 18th Jan. 1879 and took detail notes of her construction and machinery. He may have even gone on a trials run. With the added armament weight her speed dropped from 18 to 17.5 kts. (Figure 8). [25]

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

[25] Nat Herreshoff’s notes of HMS LIGHTNING are contained in “Nathanael G. Herreshoff Design Notebook 1877 -1879. Nathanael G. Herreshoff Collection. Model Room Archival Boxes, Herreshoff Marine Museum. Access courtesy Halsey C. Herreshoff.

Figure 7- HMS LIGHTNING as delivered in 1877. Thornycroft image.

Figure 8- HMS LIGHTNING configured with forward mounted torpedo gun & on-deck storage for two torpedoes. “1881” on verso dates photo to when the brothers delivered two 48-foot videttes to the Admiralty (HMCo #74 & 75). The order won in 1879 from the Admiralty impressed by the performance of HMCo #44. Source- Nathanael G. Herreshoff Collection. Access courtesy Halsey C. Herreshoff.

On Jan. 22, 1879, Nat sketched in his notebook the dimensioned profile of a 200-ft. Torpedo Cruiser “tendered to the Admiralty with specifications” the apparent proposal from an unidentified British shipbuilder.[26] (Warships variously identified as “Torpedo Cruisers”, Torpedo Catchers” and “Torpedo Gunboats” were designed and built for the world’s navies starting about 1876 with a mission to “resist and attack these pests (i.e. torpedo boats) at sea”. Larger, with heavier armament and more capable at sea they were slower than the torpedo boats they were meant to chase and never proved very effective. That all changed in 1893 when Yarrow built for the Admiralty the first, high-powered, high-speed torpedo destroyer.)[27]

[40] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. Washington GPO 1881 Pgs. 3, 5, 6.

[26] “Outline sketch of Torpedo cruiser tendered the Admiralty with specifications”, Jan. 22, 1879”, NGH Design Notebook 1877 -1879. Nathanael G. Herreshoff Collection. Herreshoff Marine Museum. Access courtesy Halsey C. Herreshoff.

[27] Lieut. G. E. Armstrong, Late RN, Torpedoes and Torpedo-Vessels. Part of the Royal Navy Handbook Series, edited by Cdr. C. N. Robinson, RN. (George Bell and Sons, London, 1896). Chapters XII & XIII, “Torpedo Catchers” & “Torpedo Destroyers”. Pgs. 213-229.

The brothers must have returned from their 1879 and 1881 trips to England encouraged by the reception received by them and their vessels. With the advent of the initial planning for the “New American Navy” including actions to understand and achieve the competency of the Royal Navy, the Herreshoff brothers most likely entertained the hope, maybe even the expectation, that the US Navy would depend upon private industry (i.e., Herreshoff) for their torpedo boat designs.

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

Nat Herreshoff's Model Testing of 1880

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

The most significant event coming out of the 1879 trip to England and acquisition of the INA Transactions was Nat’s extensive model towing tests in Oct.-Nov. 1880.

[40] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. Washington GPO 1881 Pgs. 3, 5, 6.

The Model Testing of William Froude

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

We introduced William Froude’s work In Part 3 LIGHTNING: A Win for the Herreshoff System.

[40] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. Washington GPO 1881 Pgs. 3, 5, 6.

Froude, trained as a mathematician, looked beyond the rule of thumb methods of the day to predict ship’s speed based upon model tests. Starting with tests on lakes of small self-propelled models driven by clockwork, to a small tank with models towed by a cord with a falling weight, he convinced the Admiralty in 1871 to fund a large experiment tank at Torquay. Featuring a 165 feet long, 36 feet wide, 10 feet deep test section where generally 10-foot long, hollow, 1 ½ inch thick, molded paraffin models weighing 200 pounds, suspended from a carriage towed by a steam powered endless wire rope, were tested. Looking forward to Nat’s testing of 4 ½ foot long models we note that in Froude’s early tests of 1868 he found models of 3-foot length exhibited slight excess of resistance attributable to non-scalable effects not found in tests of 6- and 12-foot models. He postulated it is, “fair to then conclude that models of say 6 feet long and upwards will be to all intents and purposes unimpeded by such “rigidity” as exists in water.”[28]

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

[28] William Froude The Papers of William Froude 1810-1879 (The Institution of Naval Architects, London, 1955). Contains the following sources for details of Froude’s testing. Sir Wescott Able, Royal Corps of Naval Constructors, Ret. “William Froude – A Memoir”. Pgs. xi-xiv. R. W. L. Gawn, Royal Corps of Naval Constructors, VP INA, “An Evaluation of the work of William Froude” Pgs. xv-xvii. William Froude, “Description of a Machine for Shaping the Models Used in Experiments on Forms of Ships”. Pgs. 206- 207. “Observations and Suggestions on the Subject of Determining by Experiment the Resistance of Ships”. William Froude memorandum to Mr. E. J. Reed, Chief Constructor of the Navy, Dec. 1868. Pg. 121.

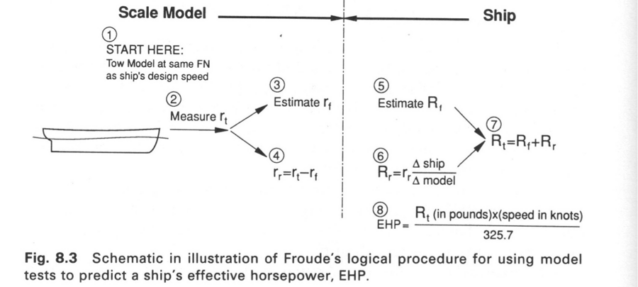

Froude’s objective was to use model tests to predict the full-scale ship’s resistance and from that determine the horsepower to drive the ship at design speed. Froude understood that the total resistance was the sum of two components, friction resistance and wave making (referred to as residual resistance), and that they followed different physical laws in scaling from model to full scale, and therefore needed to be treated separately.[29] He determined by simple towing tests of flat planks the friction resistance varied directly with the wetted surface area of the underwater hull, with factors for ship speed and surface roughness. He also observed that ship and model produced the identical (to scale) wave profiles when moved at the same non-dimensional speed/size (length) ratio known as the Froude Number (FN).

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

[29] Discussion of total resistance, it’s two elements, and scaling from model tests to full scale is taken from Harry Bedford, Naval Architecture for Non-Naval Architects, (SNAME, Jersey City, NJ, 1991). “Model Basin Theory” pages 51-2, 95-6.

Froude determined total resistance by measuring the pounds of pull required to tow the scale model at the FN corresponding to the ship’s design speed. (Figure 9) He then calculated the amount contributed by frictional resistance, subtracting that from the total to give the residual resistance of the model. To predict the full-scale ship resistance, he first estimated frictional resistance of the ship’s wetted surface area. Second, the ship’s residual resistance was calculated as the model’s residual resistance multiplied by the ratio of their displacements. The sum, total ship resistance, was used to calculate ship’s effective horsepower.

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

Figure 9- Froude’s Model Test Procedure to Predict Ship’s EHP (Source Benford, Naval Architecture for Non-Naval Architects. SNAME 1991. Page 96.)

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

Nat Herreshoff Model Test Background and Records

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

In the story of LIGHTNING, Part 3 of this series we introduced this undated (but identified to May 1897 by analysis) scrap of paper written in Nat Herreshoff‘s hand, contained in the George A. Converse Collection, DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist Univ:[30]

[40] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. Washington GPO 1881 Pgs. 3, 5, 6.

[30] George Albert Converse papers and photographs, 1861-1897 MSS 0068 Box 1, Folder 10 DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University

“Date of Model Towing Experiments

1876. Before designing LIGHTNING

October and November 1880 before designing STILETTO and others

November 1895 before designing #6 and 7 (i.e., PORTER & DuPONT)

August 1896 before making decision for 30 knot torpedo boat.”

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

We also introduced Cdr. Converse letter to Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt defending the results of the PORTER (TB-6) Navy Acceptance Trials in which he described the towing model testing for LIGHTNING and STILETTO. Converse witnessed the LIGHTNING tests, but not the 1880 tests as he had been transferred from Newport.[31]

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

[31] George Albert Converse papers and photographs, 1861-1897 MSS 0068 Box 1, Folder 4 DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University

“Prior to commencing the construction of this boat (LIGHTNING), Mr. N. G. Herreshoff made a series of experiments with models, towing them under conditions which would demonstrate the power required for propulsion, the form of hull best suited for speed, and determine other qualities which the boat should possess…”

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

“During the year 1880, similar but much more exhaustive experiments were made and in accordance with the data then obtained the STILETTO was built; and that boat (the displacement according to the Naval Register being only 31 tons) with the unusually large trial weight of 9 1/4 tons on board, maintained for three hours a speed of 18.23 knots which was greatly in excess of that attained abroad, at that time by boats of comparative size under like conditions.”

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

While we have not found the LIGHTNING tests, there are records of the Oct- Nov. 1880 tests in the N. G. Herreshoff Collection. The following discussion is based upon the records identified in this end note.[32] As this is the first evaluation of these tests it may very well contain errors and incorrect conclusions as to how the tests were conducted. There is no doubt however in our understanding of Nat’s overall approach to model testing, the test results achieved and how they influenced the design of STILETTO. Therefore, we will discuss these subjects first and then follow with a less certain discussion of how the 1880 tests were conducted.

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

[32] NGH Model Test Records- Records of comparative models tests Standard model A to Models C & D includes dated Oct & Nov 1880 and undated test data (MRDE05_01760.jpg, MRDE07_02150.jpg, MRDE07_02160, MRDE07_02170, MRDE07_02180, MRDE07_02190). Curves of Resistance of Models- Experiments made October 1880. Models A, C & D includes midship section profiles (WRDT08_05310.jpg). Nathanael G. Herreshoff Collection. Access courtesy Halsey C. Herreshoff. See also JJP NGH Towing Experiments Oct.- Nov. 1880 Notes, Aug. 11, 2021.

Nat Herreshoff’s Comparative Test Approach

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

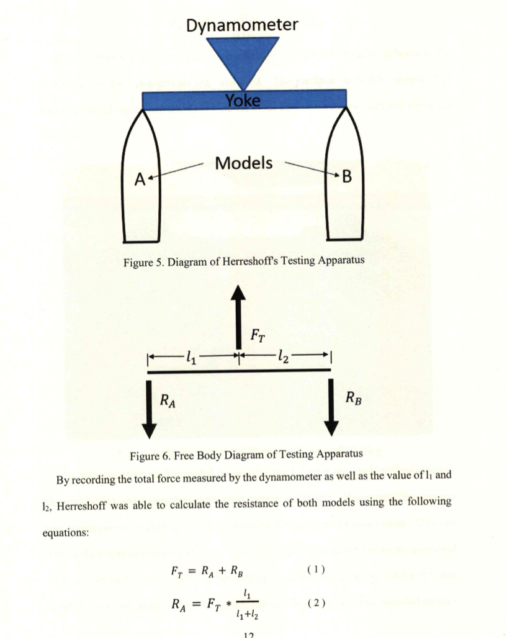

Nat simplified Froude’s method. He conducted comparative tests where the total resistance of a test model was compared to the total resistance of a standard model. All the models measured 4½ feet in length. Frictional resistance was minimized- in some tests he notes, “Models varnished and rub down with wax and sperm oil.” Since all models were the same length, and therefore had closely similar underwater surface area, Nat assumed the difference in total resistance between models was due to differences in residual resistance, related to underwater hull form and therefore scalable to the full-size vessel. The test configuration and method of calculating the total resistance of each model is shown in Figure 10.

[40] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. Washington GPO 1881 Pgs. 3, 5, 6.

1880 Model Test results Determine the Hull Form of STILETTO.

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

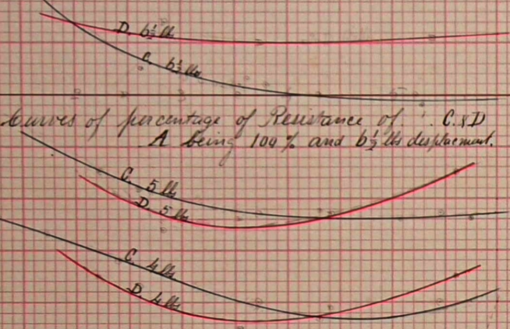

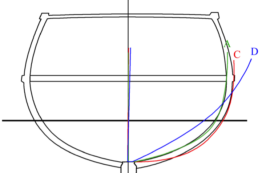

About 74 tests were conducted with double ender Model A as standard against double ender Models C and D at different speeds, different displacements, and different trims (weights applied at the stern}. Figure 11 compares the total resistance of the models. At the heaviest displacement, 6½lbs., Model A had the lowest resistance at low speeds and Model C the lowest resistance at high speeds. For lighter displacement tests, C had lower resistance than D. at moderate to high speeds. The model test speeds 1.5 to 5.5 kts equate to 6.7 to 24.5 kts for the 90-foot wl STILETTO.

[40] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. Washington GPO 1881 Pgs. 3, 5, 6.

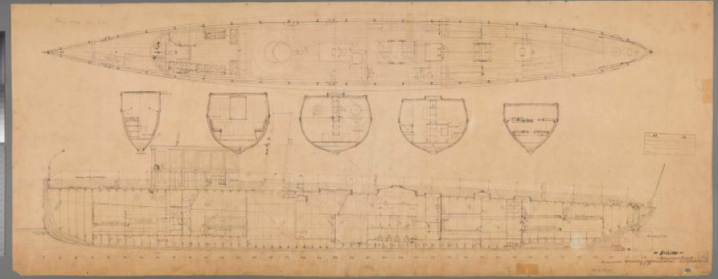

Figure 12 shows the double ender Model C. Figure 13 shows the hull form of STILETTO as originally built, “Torpedo Boat fitted as yacht”. Figure 14 comparing STILETTO’s midship section to the midship section profiles of Models A, C & D clearly show Nat designed STILETTO with a midship profile closely matching the better performing Models A & C.

[40] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. Washington GPO 1881 Pgs. 3, 5, 6.

Figure 10- Nat Herreshoff Model Testing Apparatus Diagram & Model Resistance Calculation- Model A is standard. Model B above is test position for Model C & D. (Source Kelly J. O’Brien, A Modern Analysis of the Torpedo Boats PORTER and DUPONT, Thesis Webb Institute, Glen Cove, NY. June 2016. Pg. 12.)

[40] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. Washington GPO 1881 Pgs. 3, 5, 6.

Figure 11- Oct-Nov 1880 Model Tests Curves of Percentage of Resistance of Models C & D with A being 100% and 61/2 lbs. Displacement for Speeds 11/2 to 51/2 Knots (Source WRDT08_05310. Nathanael G. Herreshoff Collection. Access courtesy Halsey C. Herreshoff)

[40] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. Washington GPO 1881 Pgs. 3, 5, 6.

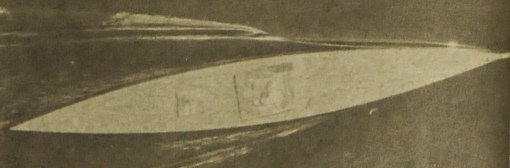

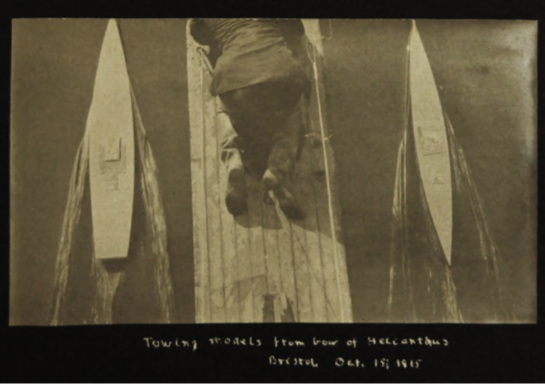

Figure 12- Model C during test Oct 15, 1915. Herreshoff Marine Museum scan_913.

[40] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. Washington GPO 1881 Pgs. 3, 5, 6.

Figure 13- STILETTO HMCo #118 As Originally Built “Torpedo Boat fitted as yacht” (Source HMCo Drawing 119-016, HH.5.09732, Haffenreffer-Herreshoff Collection, MIT Museum.

[40] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. Washington GPO 1881 Pgs. 3, 5, 6.

Figure 14- Comparison STILETTO Midship Section to the Midship Section Profiles of Test Models A, C & D. (Compiled by Evelyn Ansel, Curator Herreshoff Marine Museum from WRDT08_05310. Nathanael G. Herreshoff Collection. Access courtesy Halsey C. Herreshoff and Midship Section from HMCo Dwg 4-34 HH.5.00216, Haffenreffer-Herreshoff Collection, MIT Museum)

[40] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. Washington GPO 1881 Pgs. 3, 5, 6.

Conduct of the 1880 Model Tests

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

There is more to be learned about conduct of the tests. Nat did not leave us a written test plan, describing the objectives, test method, model designs (including the basis for the designs), design of the tests, consistently recorded test results, written conclusions, and description of how these influenced future designs. These are items that are presented more clearly in the later tests of 1895 and 1896. The 1895 test supported the development of the design for PORTER and DUPONT. Nat was responding to a Navy Request for Proposal (RFP) requirement for a 26-knot torpedo boat, except that Herreshoff was guaranteeing 27.5 knots. The 1896 test was responding to a Navy RFP requirement for a shipbuilder design to achieve 30 knots. Models were tested as per Figures 10 and 15 from a platform suspended from the bow of a power vessel. Speed of the test was governed by engine RPM that had been calibrated to vessel speed.

[40] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. Washington GPO 1881 Pgs. 3, 5, 6.

Figure 15- Model Tests Oct 15, 1915. Model C is on the right. Herreshoff Marine Museum scan_913.

In 1880 the individual test runs were conducted over a 608 ft. long course. The course length is identified in one specific set of 46 tests and the test times of the other 30-odd tests suggest the same length. Speed of the model was determined by recording the time to complete the 608-foot course. The location of the course is not identified. How they were towed is not described, however one test mentions, “Towed by bowsprit to prevent sheering.” Recorded data include displacement in pounds of both the standard and test models, the course time, total resistance of both as measured by the dynamometer, calculated resistance of both the standard and test models (as per the calculation method of Figure 10), with notes on placement of weights, underwater surface finish of the models and water conditions that could affect the results. We don’t know the basis upon which Nat designed Models; A, C and D. Model A is lost; C and D are among the ten models that survive. Written on Model C are the words “Used on the standard end of beam. Model C made about 1880 NGH.” This adds to the unknowns, since test data identifies Model A as the standard.

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

An Awakening US Navy

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

In “Lightning, Part 3” we introduced the new Secretary of the Navy William H. Hunt who in March 1881 undertook to implement President Garfield’s call for expansion and modernization of the Navy. Working through a Navy Advisory Board (the Rodgers Advisory Board), recommendations to build the nucleus of a modern Navy that could be enlarged in an emergency, were presented to Congress. In FY 1882 Congress added a new annual budget line item- “Increase in the Navy” to fund the ships and in 1883 it legislated “ships should be constructed as recommended by the Advisory Board”. Progress was slow and ships were never built in the numbers recommended by the Rodgers Board and its successors, but the Boards provided a consistency of recommendations to guide Congress and subsequent Secretaries of the Navy in the development of the “New Navy”.[33] [34]

[40] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. Washington GPO 1881 Pgs. 3, 5, 6.

[33] Rodgers Advisory Board Appointing Order June 29, 1881 & Rodgers Advisory Board Report Nov. 7, 1881, Appendix #1, Secretary of the Navy Annual Report 1881 (Wash DC, GPO 1881) Nov. 28, 1881. pp 6, 27-81. Board’s Torpedo vessel recommendations pg. 37.

[34] John D. Long, Secretary of the Navy 1897- 1902, The New American Navy, (The Outlook Co. New York) 1883. Pg. 33. On Congress legislating “ships should be constructed as recommended by the Advisory Board”.

There was a new sense of purpose throughout the Navy. Commodore Montgomery Sicard the new Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance (BuOrd), recognizing the wide adoption of the Whitehead torpedo, pushed for the US Navy introduction of the automobile torpedo as “a matter of the greatest importance and urgency.”[35] For the first time in six years Secretary Hunt published Admiral of the Navy David Dixon Porter’s Annual Report as an appendix to his report. Porter sounded a call to action- For years people have been saying “let’s wait until the Europeans finish their costly experiments and then let us imitate the best type of war vessels built abroad.” It is now time to delay no longer to be “ready to meet any emergency”. Our national debt is melting away our internal commerce exceeds that of any European nation yet “we are at the mercy of any foreign nation that chooses to make war on us…” He proposed a 52 ship, $48-50 M building program of iron and steel warships including 20 torpedo boats with steel decks and facing of 100 tons and great speed.[36] In February 1881 Passed Assistant Engineer John A. Tobin, USN (Barrington, RI born and inventor of the Tobin Bronze used by Herreshoff in the 1893 Americas Cup defender VIGILANT) was ordered to Glasgow Scotland to obtain information on the latest warships including the purchase of plans and specifications. He was granted unfettered access in England and Scotland including the Admiralty Experimental Works at Torquay, detailed information of the properties, manufacturing processes and tests of the latest steels and armor plate, details of the latest boilers from Thornycroft and Yarrow including the results of torpedo boat trials and much more. At Congress direction it was printed by the Bureau of Steam Engineering (BuSteam) in a 260-page widely distributed document, Improvements in Naval Engineering in Great Britain.[37] And in September 1884, George Converse, then in London, is believed to have witnessed the trials of Thornycroft’s latest torpedo boat built for the Danish Navy.[38]

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

[35] Thomas Wildenberg & Norman Polmar, Ship Killers, (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2010). Pg. 20.

[36] “Report of the Admiral of the Navy” June 19, 1881. Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy 1881. Appendix #4. Pgs. 97, 102.

[37] “Report to the Bureau of Steam Engineering”, Army and Navy Journal, July 8, 1882, pg. 1146

[38] “John Thornycroft letter Sept. 11, 1884” invites Converse to witness the trials. Series 1, Box 1, Folder 3, George Albert Converse Papers and Photographs (MSS 0068x), DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University.

In his 1881 report to Congress Hunt projected by FY 1883 a Navy expenditure increase of 35% to just over $20 million, and a doubling of the Ordnance and Torpedo Corps expenditures to $500,000.[39] The Appropriation Acts of Aug. 5, 1882, and Mar. 3, 1883, authorized construction of the ABCD ships (representing the three main types of unarmored cruisers and a dispatch vessel). To ensure that new thinking guided the process Congress further directed the vessels be built under the advice and supervision of the Naval Advisory Board. This put the Board in the position of both establishing the requirement and directing the implementation thereby setting up a new challenge to the authority of the Navy Bureaus to control the detail design and construction of the ships of the “New Navy”.[40]

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

[39] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. (Wash DC GPO, 1881) Pgs. 20-21.

[40] Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy 1883 (Wash DC, GPO 1883) Dec. 1, 1883. Pgs. 3-4.

The Developing Business Opportunity for US Navy Torpedo Vessels

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

The Rodgers Board recommended a 121 ship Navy to provide “the effective defense for our coast in the sudden emergency of the outbreak of war and hold the enemy in check until armored vessels can be supplied to perfect the defense and undertake offensive operations.” The proposed force was to include 68 new ships to be built over the next eight years at a cost of $29.6 million; 38 unarmored steel and wood cruisers in four classes, 5 steel rams, and 25 torpedo vessels as follows;[41]

[40] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. Washington GPO 1881 Pgs. 3, 5, 6.

[41] “Report of the Rodgers Board Nov. 7, 1881” Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. (Wash DC GPO, 1881 Pgs. 37-8.

- 1. Five Sea-going Torpedo Gun Boats- To prevent establishment of an effective coastal blockade.

- • Carrying a powerful bow gun. LBP 125 ft; 470 tons, max. speed not less than 13 kts. Cost each $145K. Total $725K.

- 2. Ten Herreshoff Steel Harbor Torpedo Boat Type- For strict channel and harbor service.

- • About 70 feet long, max speed not less than 17 kts. Cost per vessel complete and ready for service $25,000. Total cost $250K.

- 3. Ten Steel Cruising Torpedo Boats- Reinforcement to the rams and torpedo gunboats or the harbor boats.

- • About 100 feet long, max. speed not less than 21 kts. Cost each complete and ready for service $38,000. Total cost $380K.

This was the market opportunity available to Herreshoff with one addition- supporting the Newport Naval Torpedo Station should they require a high-speed vessel for testing the automobile torpedo. Looking at the list they must have been pleased. Nat had researched torpedo gun boats in England; it offered a machinery opportunity. The harbor torpedo boats were a Herreshoff win, if an imminent threat developed, the contracts were sure to follow. A 100-foot-high speed vessel was not out of reach of their evolving capability; the challenge being to do in steel hulls what they had been doing in wood.

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

In Part 5 we explore these opportunities and complete the story of STILETTO.

[40] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. Washington GPO 1881 Pgs. 3, 5, 6.

[1] Stewart A. McKenna & Larrie D. Ferreiro, “The Scientific and Management Revolution and Shipbuilding on the ‘Two Clydes’ 1880-1900.” Nautical Research Journal Vol.58, No. 2 Summer 2013. Pages 105-128. All information about the shipyards on the Clyde and the Delaware, their technology, and dates of the technology are taken from this research paper.

[2] William duBarry Thomas. “The Genesis of a Professional Society”. SNAME Transactions. Vol.101, 1993, pgs.31-9.

[3] “Marine Engineering”, IRON, London, Jan. 19, 1883. Pg. 55.

[4] For example, John L. Thornycroft, “On the Resistance Opposed by Water to the Motion of Vessels of Various Forms and the Way in Which This Varies with the Velocity”, Transactions, INA Vol. 10, 1869. William Yarrow, “Some Experiments to Test the Resistance of a First Class Torpedo Boat”, Transactions, INA Vol. 24, 1883. A copy of the Yarrow paper was available to George Converse and is in his archives Series 1, Box 1, Folder 16, George Albert Converse Papers and Photographs (MSS 0068x), DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University.

[5] Edgar C. Smith, A Short History of Naval and Marine Engineering, (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK, 1938). Chap. XVII “Machinery of Torpedo Craft”, pp 254- 270

[6] Carlton J. Pinheiro Editor, Recollections and Other Writings by Nathanael G. Herreshoff, “The Log of the RIVIERA.” & NGH “Notes from Memory March,1932.” (Herreshoff Marine Museum, Bristol, RI, 1998) Pages 81-92. Nat writes that one day they cruised the Thames to a little beyond Cheswick (Chiswick). Chiswick was the site of the Thornycroft yard, but he does not mention the yard. In view of Nat’s intense interest in ships, shipbuilding, and self-study it is believed that he visited several shipyards on RIVIERA’s 1874 cruise, but the only one he mentions is the shipyard and machine shops of the Maritime Company; “largest thing of the sort in France” where he saw large boiler and engine works. Pg. 85.

[7] “Modern Torpedo Boats.” Reprint from Scribner Magazine. Newport Mercury, April 9, 1887.

[8] Orison Swett Marden. How They Succeeded: Life Stories of Successful Men Told by Themselves. (Boston: Lothrop Publishing Co., 1901) “Chapter XVII John B. Herreshoff, The Yacht Builder”. Pages 280-1; 287-8. (Other business leaders featured include Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller, further evidence of John’s stature in American business.)

[9] In 1926 Nat Herreshoff was provided six Herreshoff biographies from the 1904 volume of The National Cyclopedia of American Biography. From 1926 into the early 1930s. Nat undertook to correct and add to the published biographies of himself and his two older brothers, James and John. The drafts of his biographies can be found in one small folder of Mystic Seaport’s L. Francis Herreshoff Collection 138- Box 16, Folder 13. The papers are very important to a better understanding of how Captain Nat viewed both his life and career, and the part his two brothers played in the founding and shaping of the Herreshoff Manufacturing Company. They were analyzed in a 2019-20 four-part Curator’s Log series, “Captain Nat and the Herreshoff Biographies”. In addition to addressing “Product Lines” his draft autobiography;

Characterization- identifies himself as a “marine engineer and yacht designer” rather than the Cyclopedia’s “boat builder and designer”.

Success- Nat describes success at every stage of his life; boatbuilding and sail racing as a youth, steam engineering at MIT and Corliss, and designing and superintending at HMCo.

Defense of 1901 America’s Cup Contender CONSTITUTION- Capt. Nat was forever sensitive about the criticism he received when his new CONSTITUTION lost in the defender trials to his 1899 boat COLUMBIA.

Credits & Family- Credits his forefathers for his early love of the sea and vessels; blind brother John for introduction to boats and mechanical things at an unusually young age; for steam engineering, opportunities offered by Mr. Corliss; brother John for their “successful and well-known business”; Commodore Edwin Morgan for his part in HMCo’s “world-wide reputation” in sailing yachts.

[10] Benjamin F. Isherwood letter to Nathaniel G. Herreshoff, October 21, 1899. Nathanael G. Herreshoff Collection. Herreshoff Marie Museum. Access courtesy Halsey C. Herreshoff. (It is interesting that Isherwood always wrote “Nathaniel” with the “ie”, rather than the “ae” used by Nat in his adult years.)

[11] VAMOOSE never made it to the West Coast. The President of the railway across the Isthmus of Panama refused to transport VAMOOSE because of an article Hearst’s newspaper had written slandering the President’s daughter. See “William Randolph Hearst, The Herreshoffs and the Yacht VAMOOSE: Parts 1 and 2”, Curator Log 2012. Herreshoff Marine Museum.

[12] Draft of Nat Herreshoff’s autobiography Mystic Seaport, L. Francis Herreshoff Collection 138- Box 16, Folder 13.

[13] N. G. Herreshoff letter to L. F. Herreshoff, October 29, 1935. Mystic Seaport L. Francis. Herreshoff Collection 138 Box 17, Folder 11.

[14] L. Francis Herreshoff ltr. to Uffa Fox of Oct. 22, 1935, pages 3-6, responding to Uffa Fox ltr. of Oct. 5, 1935. Mystic Seaport L. Francis is Herreshoff Collection 138. Box 1, Folder 5. LFH provided comments about his father in response to Uffa’s desire to create a “word picture” of Nat Herreshoff.

[15] Ibid, pages 1 & 2.

[16] NGH letter to LFH, October 29, 1935. Mystic Seaport L. Francis. Herreshoff Collection 138 Box 17, Folder 11.

[17] “The Herreshoff Manufacturing Co. Works”. Bristol Phoenix, April 13. 1878.

[18] Nathanael G. Herreshoff, Design Notebook No. 1. Nathaniel G. Herreshoff Collection, Herreshoff Marine Museum. Access courtesy Halsey C. Herreshoff. There are five such notebooks prepared chronologically covering the years 1878 to the spring 1934. Some are titled “Naval Architecture & Engineering Notes” and include Nat’s notes for individual vessel designs, design changes, shop reports of actual vessel weights, open-water model tests, various material tests, and design standards. Design Notebook No. 1. is unique- covering machinery, fittings and containing Nat’s personal listing of the construction record for steam vessels #1- #194. This listing is organized as the “HMCo Construction Record, Appendix C.” Guide to the Haffenreffer-Herreshoff Collection. Hart Nautical Collections, MIT Museum, 1997, except that there are some differences in the commentary.

[19] “The Herreshoff Manufacturing Co.”, Boston Journal of Commerce, April 2, 1881.

[20] “Bristol Property Taxes”. Bristol Phoenix Aug. 11, 1883, and subsequent Bristol Phoenix annual property tax reports through 1898.

[21] Frederick J. Rowan A.M.I.C.E., M.I.E.S. The Practical Physics of the Modern Steam Boiler. (P. S. King & Son, London; D. Van Nostrand, New York, 1903). Pg. 481.

[22] The details of HMCo #44 are taken from (1) “Torpedo Boat Experiments” Irish Times, Jan. 10, 1879, page 3. (2) “The Herreshoff Torpedo Boats” Recent Practice in Marine Engineering Two Volumes. Edited by William Henry Maw. Publisher: London Offices of Engineering, London & J. Wiley & Sons New York 1884. Pages 280-6. This document is available online at www.hathitrust.org. All quotes about HMCo #44 are from this paper.

[23] Nathaniel Barnaby, Knights Commander of the Bath, VP Institution of Naval Architects, Former Director of Naval Construction, British Admiralty, Naval Development in the Century. (Linscott Publishing Co. Philadelphia; W & R Chambers Limited, London, 1904) pp 127-129.

[24] Ibid., page 129.

[25] Nat Herreshoff’s notes of HMS LIGHTNING are contained in “Nathanael G. Herreshoff Design Notebook 1877 -1879. Nathanael G. Herreshoff Collection. Model Room Archival Boxes, Herreshoff Marine Museum. Access courtesy Halsey C. Herreshoff.

[26] “Outline sketch of Torpedo cruiser tendered the Admiralty with specifications”, Jan. 22, 1879”, NGH Design Notebook 1877 -1879. Nathanael G. Herreshoff Collection. Herreshoff Marine Museum. Access courtesy Halsey C. Herreshoff.

[27] Lieut. G. E. Armstrong, Late RN, Torpedoes and Torpedo-Vessels. Part of the Royal Navy Handbook Series, edited by Cdr. C. N. Robinson, RN. (George Bell and Sons, London, 1896). Chapters XII & XIII, “Torpedo Catchers” & “Torpedo Destroyers”. Pgs. 213-229.

[28] William Froude The Papers of William Froude 1810-1879 (The Institution of Naval Architects, London, 1955). Contains the following sources for details of Froude’s testing. Sir Wescott Able, Royal Corps of Naval Constructors, Ret. “William Froude – A Memoir”. Pgs. xi-xiv. R. W. L. Gawn, Royal Corps of Naval Constructors, VP INA, “An Evaluation of the work of William Froude” Pgs. xv-xvii. William Froude, “Description of a Machine for Shaping the Models Used in Experiments on Forms of Ships”. Pgs. 206- 207. “Observations and Suggestions on the Subject of Determining by Experiment the Resistance of Ships”. William Froude memorandum to Mr. E. J. Reed, Chief Constructor of the Navy, Dec. 1868. Pg. 121.

[29] Discussion of total resistance, it’s two elements, and scaling from model tests to full scale is taken from Harry Bedford, Naval Architecture for Non-Naval Architects, (SNAME, Jersey City, NJ, 1991). “Model Basin Theory” pages 51-2, 95-6.

[30] George Albert Converse papers and photographs, 1861-1897 MSS 0068 Box 1, Folder 10 DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University

[31] George Albert Converse papers and photographs, 1861-1897 MSS 0068 Box 1, Folder 4 DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University

[32] NGH Model Test Records- Records of comparative models tests Standard model A to Models C & D includes dated Oct & Nov 1880 and undated test data (MRDE05_01760.jpg, MRDE07_02150.jpg, MRDE07_02160, MRDE07_02170, MRDE07_02180, MRDE07_02190). Curves of Resistance of Models- Experiments made October 1880. Models A, C & D includes midship section profiles (WRDT08_05310.jpg). Nathanael G. Herreshoff Collection. Access courtesy Halsey C. Herreshoff. See also JJP NGH Towing Experiments Oct.- Nov. 1880 Notes, Aug. 11, 2021.

[33] Rodgers Advisory Board Appointing Order June 29, 1881 & Rodgers Advisory Board Report Nov. 7, 1881, Appendix #1, Secretary of the Navy Annual Report 1881 (Wash DC, GPO 1881) Nov. 28, 1881. pp 6, 27-81. Board’s Torpedo vessel recommendations pg. 37.

[34] John D. Long, Secretary of the Navy 1897- 1902, The New American Navy, (The Outlook Co. New York) 1883. Pg. 33. On Congress legislating “ships should be constructed as recommended by the Advisory Board”.

[35] Thomas Wildenberg & Norman Polmar, Ship Killers, (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2010). Pg. 20.

[36] “Report of the Admiral of the Navy” June 19, 1881. Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy 1881. Appendix #4. Pgs. 97, 102.

[37] “Report to the Bureau of Steam Engineering”, Army and Navy Journal, July 8, 1882, pg. 1146

[38] “John Thornycroft letter Sept. 11, 1884” invites Converse to witness the trials. Series 1, Box 1, Folder 3, George Albert Converse Papers and Photographs (MSS 0068x), DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University.

[39] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. (Wash DC GPO, 1881) Pgs. 20-21.

[40]Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy 1883 (Wash DC, GPO 1883) Dec. 1, 1883. Pgs. 3-4.

[41] “Report of the Rodgers Board Nov. 7, 1881” Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. (Wash DC GPO, 1881 Pgs. 37-8.