May 11, 2021

The Herreshoff Brothers and their Torpedo Boats, Part III: LIGHTNING – a win for the Herreshoff System

A series of papers on bringing innovation to the "New Navy"

by John Palmieri

Introduction

Our story begins with the election of President Grant in November 1868 and covers the ascendancy of Vice Admiral Porter to leadership of the Navy, the establishment of the Torpedo Station in Newport Rhode Island, development of the Herreshoff safety coil boiler, the acquisition of LIGHTNING and the recognition of the superiority of the Herreshoff System.

See on-line THE HERRESHOFF CATALOGUE RAISONNÉ for detailed information on HMCo. # vessels including photos, half model images and descriptive documents

Vice Admiral David Dixon Porter in Charge

Dealing with Isherwood

Ulysses S. Grant was elected President in November 1868. In January 1869 Grant advised Congress that it was his intention to appoint Porter, an active-duty Navy officer, as his Secretary of the Navy. Congress objected to this challenge to civilian control, therefore following his inauguration on March 4, 1869 Grant installed a figurehead Secretary, Adolph E. Borie, and five days later ordered Porter to Wash. DC by special train to take effective charge of the Navy. Outgoing Secretary Welles commented Borie “was a passive tool. He is now a mere clerk to Vice Admiral Porter.”[1]

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

On his first day in office, March 10, Porter issued a pile of general orders enhancing line officer control of the Navy,[2] including the nomination to Congress of James W. King to be Chief of the Bureau Steam Engineering (BuSteam). Six days later he removed Isherwood, then 47, reduced his rank to commander and ordered him to the Mare Island Navy Yard located at the northern end of San Francisco Bay - as far from Washington as it was possible to send an Engineering staff officer. Porter then established a line board to examine “all steam machinery afloat.” The majority report submitted September 1869 was a sweeping condemnation of all steam engines built under Isherwood’s direction. (A direct repudiation of the 1864 House Committee on Naval Affairs positive report of Isherwood’s engines discussed in Part 2 Civil War and its Aftermath.)

[2] New York Herald reported in first 48 hours more general orders were issued then in the previous two years. Paul Lewis, Yankee Admiral (A Biography of David Dixon Porter). (McKay Co. New York 1968). Pg. 183.

Isherwood served out his career as one of many chief engineers, but one with special technical influence. In Nov. 1871 he escaped Mare Island returning to his home in New York City where he began serving as the senior member of various naval engineering boards and investigations. He retired from the Navy in Oct. 1884, at age 62, and in recognition of his accomplishments in over 40 years of service was promoted to a Rear Admiral.[3] (Figure 2)

[3] Sloan, Benjamin Franklin Isherwood Naval Engineer. Pgs. 228-41.

Torpedo Corps and the Newport Torpedo Station

In July 1869 Porter took the first steps to correct the Navy’s deficiency in torpedo warfare. He directed the Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance (BuOrd) to organize a Torpedo Corps manned by line officers and to establish a torpedo station to be located on former army land on Coasters Harbor Island Newport, RI., where the engineering, development, experimentation and training were to be conducted. The Torpedo Corps was assigned total system responsibility to develop the torpedo as a weapon- the explosives, torpedoes, electric generators, batteries and torpedo boats. No staff officer- constructor, steam engineer or their Bureaus had authority- they participated only at the behest of the Torpedo Corps.[4]

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

The Torpedo Corps was initially led by “Porter’s boys” who carefully selected high performing junior officers to staff the Corps. As evidence of this:

- • The first commander of the Torpedo Corps, LCDR Edmond O. Matthews, had been Gunnery Dept. Head at the Naval Academy, where he had conducted torpedo experiments under Porter’s direction. [5]

- • Capt. K. R. Breese commanding the Torpedo Station 1875-78 had been one of Porter’s Mortar Flotilla Division Commander’s, Fleet Captain of Porter’s Northern Blockading Squadron and his number two at the Naval Academy.

- • Among the young officers selected for the Corps, George Converse, and early commanding officers of the first sea-going torpedo boat, Herreshoff’s CUSHING (TB-1)- Cameron Winslow, Frank Fletcher and Albert Gleaves- all made flag rank.

[5] Ibid., pg. 17

The Torpedo Corps and torpedo development was the one new experimental/developmental initiative in the Secretary’s Annual Report of 1869. Otherwise, the watch words, in the Navy continuing through the 1870s, were economy and efficiency of a small fleet designed for overseas commerce protection, together with coastal and harbor defense.[6]

[6] “Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy, George M. Robison, Dec. 3, 1869.” House of Representatives 41st Congress 2nd Session; Message of the President of the United States with Reports of The Postmaster General and of The Secretary of the Navy, (Washington GPO 1869) Pgs. 14-15

The Newport location was significant in facilitating John Brown Herreshoff’s ability to introduce his technology to the officers of the Torpedo Corps. In August 1870, with his newly launched 38-foot open steam yacht ANEMONE (HMCo #4), John began the practice of making high-speed turns about Newport harbor in his newest boat for all to see, offering rides, disclosing particulars of each vessel, and hosting visits of his building yard.[7]

[7] Providence Evening News Aug. 24, 1870. Recounts a reporter’s ride in ANEMONE. This is not to imply that John did not advertise his vessels along much of the Atlantic coast. He conducted publicized demonstrations in New York City, Norfolk Navy Yard, Savannah, and the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. See “Advertising the Herreshoff Way”, Curator Log, October 2013.

While providing John with a unique opportunity there was a downside that became apparent in 1889 when BuOrd’s Torpedo Corps lost its system responsibility for the torpedo boat. Thereafter, torpedo boat competitors, who had been working closely with the Bureaus of C&R, and Steam on other vessel types, gained a leg up on Herreshoff.

Admiral of the Navy Porter

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

After three months of humiliation, Borie resigned. The new Secretary, George Robison, slowly worked to ease Porter out of his position of control, aided by Porter’s declining health. In a year Porter was out. Following Admiral Farragut’s death, Porter was confirmed by the Senate in January 1871, as the Admiral of the Navy; a lifetime appointment as the senior officer of the Navy; a job without fleet command, but the responsibility “to lay before the Secretary of the Navy a report on the present condition of the Navy and offer such professional suggestions as may further promote its discipline and efficiency”. This included the responsibility to oversee material inspections of the fleet. Porter took full opportunity of his position to influence policy with lengthy annual reports and engaged in correspondence with and testimony before Congress. His reports often included details on developing naval technology that one might expect from the Bureaus. Over time his influence waned. The Secretary Robeson included Porter’s report in his annual reports of 1870-75; then stopped without comment. Porter undeterred wrote them every year.[8] [9] In 1881 incoming Secretary of the Navy, William Hunt, brought a new energy, “to see to it that the Navy of the United States should not be left to perish through inaction, but should be restored to a condition of usefulness.” He sought new ideas from a Naval Advisory Board as well as Admiral Porter, publishing again the latter’s annual report from 1881-1889. (We explore this subject later in this paper.)[10]

[8] Tamara Moser Melia “David Dixon Porter: Fighting Sailor” from James C. Bradford, Editor, Captains of the Old Steam Navy: Makers of the American Naval Tradition 1840-1880. (Annapolis, MD; Naval Institute Press 1986). Pg. 242.

[9] The David Porter and David Dixon Porter Papers, 1803-1889 are housed in the Manuscript Division, William L. Clements Library, Univ. Of Michigan. (www.clements.umich.edu). In the collection is a 200+ Page document titled “My Career in the Navy Department”. It is bound with string & is too fragile to photocopy or scan. It has not been indexed. What that may add to the story we do not know.

[10] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. (Washington GPO 1881) Pg.5.

Porter Endorses an Expensive Distraction

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

In January 1871 Congress, acting largely on the recommendations of Admiral Porter, authorized $600,000 for construction of two iron-plated, spar torpedo equipped rams. The 158-foot, 340-ton ALARM, built by the New York Navy Yard “entirely from designs by Admiral Porter“ and the BuC&R /BuSteam designed, Boston Navy Yard built, 170-foot, 450 ton INTREPID. ALARM, armed with a 15-inch gun achieved a speed of 10 knots, powered by four 80 psi boilers and a pair of compound engines driving a single propeller. ALARM was used experimentally for about 10 years. INTREPID proved unsatisfactory and served for less time.[11] These large vessels were a distraction, wasting limited funds at a time when other navies were beginning to explore the “movable” automobile torpedo.

[11] “Navy Appropriation Bill” Army and Navy Journal, January 28, 1871. “The Torpedo Boat (ALARM) Launched”. New York Herald November 13, 1873. “INTREPID recently launched.” Army and Navy Journal, July 18, 1874. “Torpedo Boats ALARM & INTREPID”, Report of Adm Porter Wash. Nov. 7, 1874 contained in 43rd Congress Beginning of Second Session; Report of The Secretary of the Navy, (Washington GPO 1874) pgs. 204-20.

The Newport Years

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

Throughout his time as Admiral of the Navy, Porter maintained his residence in Washington DC and a Rhode Island summer home; first in Narragansett and in 1888 a “pretty cottage” in Jamestown. It is apparent from the “Newport (RI) Jottings” column of the US Army and Navy Journal and Gazette and the archives of the Newport Daily News that during these years Porter visited Newport for days at a time. Porter died in 1891.[12] [13]

[13] “Admiral Porter’s Big D”. Newport Aug. 5. Army and Navy Journal, Aug. 11, 1888.

[12] West, The Second Admiral, Pgs. 325-336.

Herreshoff VISION (HMCo #14) & the Safety Coil Boiler

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

Admiral Porter Shakes Things Up- Newport Summer 1873 [14]

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

[14] Report of Adm Porter Oct 22, 1873. Contained in 43rd Congress Beginning of First Session; Report of The Secretary of the Navy, (Washington GPO 1873) Pg. 276.

Porter spent a “two-month sojourn” in Newport concerned with what he perceived as a lack of interest in torpedo development. He was not happy with what he found.

“Among the officers who have studied at the torpedo station, I have met with no one who had invented anything or proposed any improvement on what has been done before. I think this is because they are not sufficiently interested.”

There was too much theoretical, and insufficient practice. There were no high-speed launches suitable for torpedo work. He also strongly advocated for the Navy to immediately publish the torpedo testing activities at Newport to better inform our own officers- “We are not so much in advance of the rest of the world that we need to keep the torpedo matters secret.”[15]

[15] Quote on publicizing torpedo developments from Report of Adm Porter Wash. Nov. 7, 1874 contained in 43rd Congress Beginning of Second Session; Report of The Secretary of the Navy, (Washington GPO 1874) Pg. 216.

Porter’s comments reinforced a July 1872 “Report of Examination of Officers Under Instructions in Torpedo- Service; US Naval Torpedo Station Newport” by a board headed by RADM John Rodgers. It recommended as “indispensable” the need for “a vessel of such speed, steering qualities, and dimensions, as will render her fit for making experiments in harbor-water and at sea with all classes of spar and towing torpedoes”.[16]

[16] “BuOrd Annual Report Oct. 17, 1872”. Contained in 42nd Congress Beginning of Third Session; Report of The Secretary of the Navy, (Wash. DC GPO 1872). Pg. 54.

Herreshoff - Creating the Technology for Speed

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

John Brown Herreshoff employed about 20 workers at his works in Bristol. He had been building steam vessels since 1868. Twenty-five-year-old Nat works for the Corliss Steam Engine Company in Providence as a draftsman and designs for John at night and on the weekends. In 1873 John has few orders. He has had to let go some workers and is looking for technology to grow the business. Increased boat speed is on his agenda.

In 1874, a physically run-down Nat takes leave from Corliss and goes to Europe where he receives two letters. In April older brother James provides the details of the “worm boiler” he has invented, and John has back fit into the 30-foot yacht CREST (HMCo #12). He relates John’s plans to install it “fast” into a bigger boat.[17]

[17] James B. Herreshoff letter to Nathanael G. Herreshoff dated April 19, 1874. Nathanael G. Herreshoff Correspondence Folder 25; Herreshoff Model Room Archive Boxes. Access courtesy Halsey C. Herreshoff.

James B. Herreshoff (1834-1930), the elder brother of the family, studied chemistry at Brown University and was subsequently employed as a manufacturing chemist. He left industry in 1870, to become a prolific inventor, spending extended periods of time abroad, primarily in England. Although James had no formal or substantive connection with the boat building business that John started and continued in partnership with Nat, he often offered unsolicited design ideas from his fertile brain. For example, the “sheets with sketches of boats and engines” he mailed to Nat during Nat’s time at Corliss.[18] After the success of LIGHTNING James represented HMCo in England and Europe, and it was through James that Englishman George R. Dunell became acquainted with Herreshoff, selling HMCo launches and torpedo boats to both the British Admiralty and the Russian Navy.

[18] Jeannette Brown Herreshoff, The Early Founding and Development of the Herreshoff Manufacturing Company. Rinaldi Printing Co. Tampa FL, 1949. Pages are not numbered. (Available Herreshoff Marine Museum archives) Quote is from an 1872 letter from Nat to James thanking him for the material.

In a May 1874 letter John, recognizing the advantage the new boiler brings to his business, encourages Nat to work with James upon his return to make something of the new invention. There is obvious tension between the two innovative brothers - Nat and James. John hopefully writes to Nat there is “room for both”. In a smart marketing move he has changed the boiler’s name to “coil”, which certainly should sell better than “worm.”[19]

[19] John B. Herreshoff letter to Nathanael G. Herreshoff dated May 29, 1874. Nathanael G. Herreshoff Correspondence Folder 25; Herreshoff Model Room Archive Boxes. Access courtesy Halsey C. Herreshoff.

Returning from Europe in September Nat is met in the Long Island Sound by recently launched 48-foot VISION (HMCo #14). John has married the coil boiler, a new high-pressure version of Nat’s single cylinder engine (a modification most likely developed by James), to Nat’s new highly efficient hull design. In a break from the past, VISION has a length to beam ratio of 13.7; more than twice that of any previous Herreshoff boat. She is capable of 15-18 mph. VISION’s performance is highly publicized and is demonstrated to officers at the Torpedo Station.[20]

[20] Nathanael G. Herreshoff, Recollections. Herreshoff Marine Museum, (Bristol RI 1998) Pg. 92 describes the meeting on Sept. 24, 1874. Contemporary news articles include; “Salt Water for Boilers“. Providence Evening Press, Sept. 7, 1874. Torpedo Station report on VISION demonstration is contained in K. R. Breese, Letter to U.S. Chief BuOrd Capt. William N. Jeffers.] Newport, R. I., October 25, 1875. In: Annual Official Report of the Secretary of the United States Navy. (Wash. DC, 1876.) Pgs. 134-5.

Later John demonstrates VISION in New York Harbor, racing against all comers. She beats everyone but the steamer MARY POWELL. John does not forget. It is a score he will settle later.

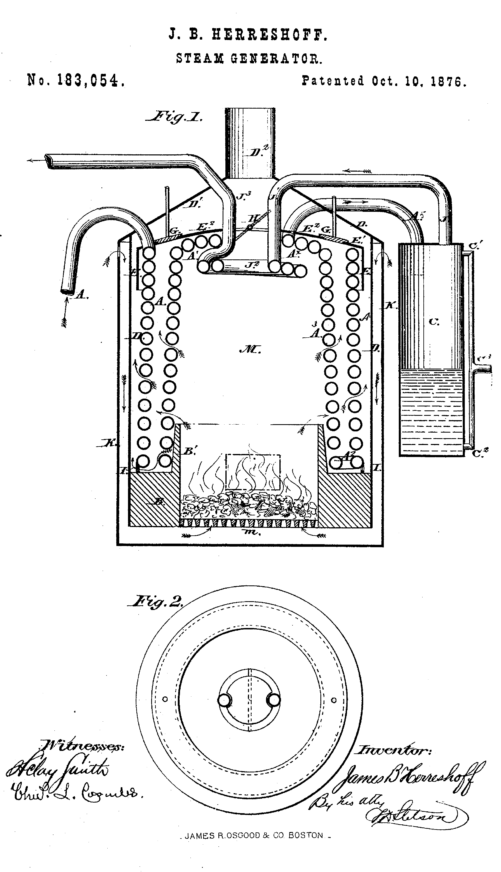

The Herreshoff Safety Coil Boiler Patent 183054 Oct. 10, 1876 (Figure 3)

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

Steam boiler explosions were a subject of current concern at BuSteam. Failures primarily in steam drums containing large amounts of steam at high temperature and pressure continued to be experienced. No real progress had been made in understanding the causes since investigations conducted nearly 40 years prior. In Nov. 1871 a Board of Engineers led by Isherwood had been appointed to witness and evaluate experiments on actual boilers.[21]

[21] “Bureau of Steam Engineering Annual Report Oct. 31, 1872”. Contained in 42nd Congress Beginning of Third Session; Report of The Secretary of the Navy, (Wash. DC GPO 1872). Pgs. 129-36.

The “Safety coil boiler” is so named because it has no steam drum. It is a type of flash boiler that depends upon high velocity steam flow through a continuous coil, rather than large steam volume in the drum, to produce power. Outwardly the coil boiler is encased within a cylindrical sheet metal shell. The firebox is contained within a continuous coil of lap-welded Iron pipe. Flow is downward through one coil and upwards through a second inner concentric coil. Heated discharge from the coil passes through a separator where steam is separated and continues through a short superheater section at the top of the boiler and on to the engine.

The coil boiler had a number of advantages for a high-speed launch application such as the spar torpedo boat.

- • No risk of explosion as there is no steam drum. Heavy wrought iron pipe including hot forged longitudinal seam and butt forged seam to join lengths to form the coil are tested at least 5-6 times working pressure vs 3½ times for shell boilers.

- • ½ the weight of competing boilers. 1/3 the weight when include the water in the system.

- • Smaller boiler cylinder saves space.

- • Raise steam to 90 psi and underway in 10 minutes from the light off. (Actual performance of LIGHTNING)

- • Can operate with freshwater or sea water. High steam flow rates keep the tubing free of scale and salts are carried into the separator and blown off.

There were disadvantages that were known from the beginning; they were outweighed by the advantages.

- • Could not mechanically clean scale from the interior of the long tube. Only time would tell if this limited boiler life.

- • Required close operator attention to maintain correct steam flow to avoid burning out tubes from inadequate flow or conversely engine damage from water carry over associated with excessive flow.

- • If coil is plugged lose all flow.

- • Not easily repaired.

- • There was a practical size limit.

LIGHTNING (HMCo #20)

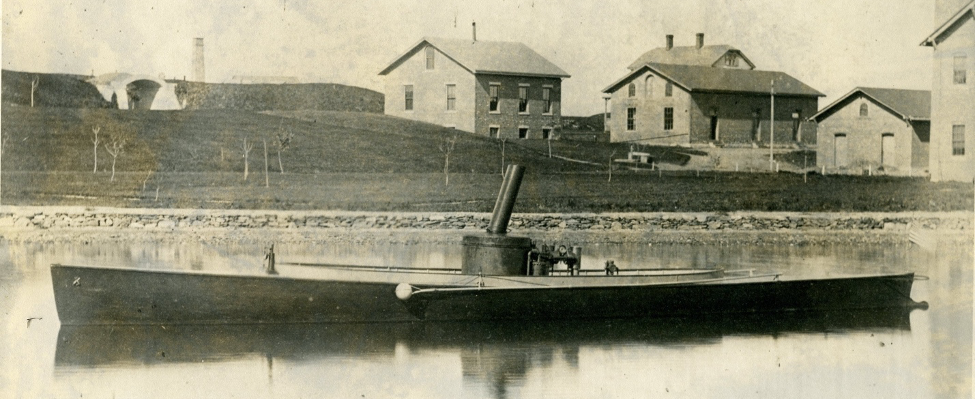

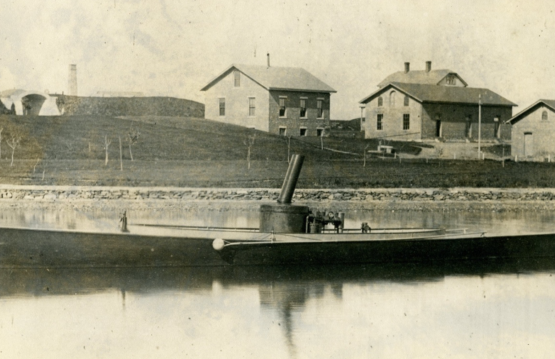

The LIGHTNING Procurement (Figure 4)

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

In 1876 the Secretary of the Navy followed Admiral Porter’s recommendation to openly report torpedo activities by having the full story of LIGHTNING’s procurement published in his annual report. It is the most extensive single vessel report to be found in any of the Secretary’s annual reports of the 1870s. The Report provided in Figure 4 includes.[22]

[22] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy on the Operations of the Department for the Year 1876, (Washington GPO 1876) Pgs. 134-142.

- • The initial Torpedo Station Report to BuOrd on Herreshoff’s VISION.

- • John Brown Herreshoff’s proposal to build a high-speed spar torpedo boat.

- • The BuOrd acceptance of the proposal with conditions.

- • The official trial report of LIGHTNING.

- • The hull construction and machinery details of LIGHTNING as delivered.

The price of $5000 was paid from a torpedo boat procurement account of ~$25,000, contained in the Torpedo Corps $123,000 annual budget. Lieut. George Converse, the Torpedo Station’s senior assistant inspector of ordnance; inspector of electricity, fuses and diving, is assigned inspector and trials officer for the LIGHTNING contract.[23]

[23] Secretary Annual Report 1876. Pgs. 110-16, 118-124,

This is the start of a close working relationship between Nat and George Converse. Converse was not only responsible for the design and provision of LIGHTNING’s spar torpedo handling equipment (At that time all armament was government designed and furnished.) but Nat began to involve Converse in model tests, early design decisions and the Torpedo Station credits him with “many improvements of the boiler and it's appurtenances were made at his suggestion and under his direct supervision.”[24]

[24] Capt. K. R. Breese USN, Inspector Ordnance, in charge of Station ltr. Nov. 23, 1876 to Chief BuOrd. Secretary Annual Report 1876. Pg. 134.

LIGHTNING Contract- Tell Us What You Want It to Do

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

After John demonstrates VISION to the Torpedo Station, he obtains a sole source contract for the Navy’s first purpose built, fast, spar torpedo boat. John’s initial offer is to build a steam-launch suitable for a torpedo boat of 55 feet (delivered at 58 feet) with a pair of engines rated at 60 hp, capable of 19 mph for ½ hour, 16-16½ mph steady speed and including a 12 hp engine for an electric light machine. BuOrd’s requirements in response are simple- build us your design; it must go 19 mph operating with sea water in the boiler for one hour.[25a]

[25] Secretary Annual Report 1876, Pg. 135-37.

Prior to the contract award the Bureau of Ordnance did its due diligence. Chief of the Bureau, Commodore Jeffers, directed an examination of the drawings, descriptions and proposal. The engineer assigned, Passed Assistant Engineer G. W. Baird, calculated the strains of the light hull and engine to be acceptable, but he was not ready to endorse the coil boiler without further test. At his recommendation a smaller Herreshoff coil boiler was purchased and fitted to a launch at Newport. The subsequent tests were successful. Baird later concluded, “The unprecedented speed of this little craft not only made the Herreshoffs famous, but called the attention of engineers to the possibilities of tubulous boilers.” [25b]

[25b] G. W. Baird, Passed Assistant Engineer USN, Comments to paper S. H. Leonard, Assistant Engineer U.S. Navy, Paper X; “Tubulous Boilers” Journal of American Society of Naval Engineers Vol 2, 1 May 1890. Pg 391.

For the brothers building a business to compete on performance this is the type of contract they seek.

- • You the customer tell us what you want it to do.

- • Do not limit or restrict us by specifying how it must be done.

- • We will design and build it for you and guarantee its performance.

Designing LIGHTNING; Setting the Process for All Herreshoff Torpedo Boats

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

Twenty-seven-year-old Nat Herreshoff started the design of LIGHTNING in November 1875 following the towing model tests discussed below. (Figure 5) From the incomplete design documents that we have found; curves, half sections and calculations, we believe Nat followed his normal design process. First, he drew a small freehand pencil sketch of the profile, midship (and possibly other) section (s), followed by preliminary calculations of weight and volume. Next was to carve a scaled half model of the of the hull from which offsets were taken (at that time paper templates) to define the shape of the hull frames. These scaled to full size were used to fabricate molds for the frames. One or more construction drawings with associated machinery, casting, etc. details defined the final product for the Herreshoff shops.[26]

There is one replica of LIGHTNING that survives to this day. Nat built a 1/12th scale model of the boat, the coil boiler, two-cylinder engine and spar torpedo. Currently in the Museum’s Model Room it is believed to have been for display only. (Figure 6)

Figure 6- 1/12th Scale model of LIGHTNING carved by Nat Herreshoff Model Room Herreshoff Marine Museum. Access courtesy of Halsey C. Herreshoff.

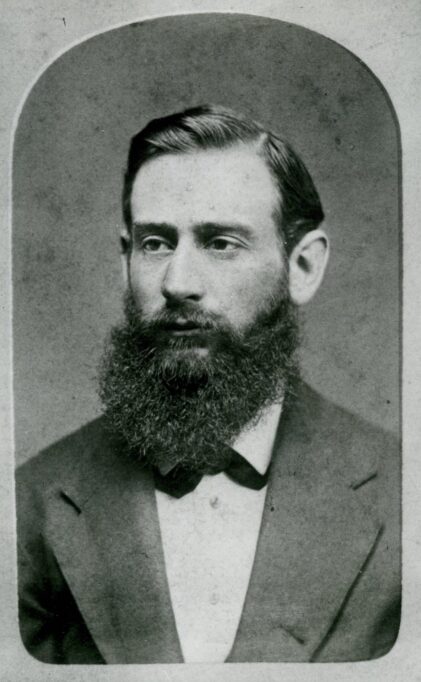

Figure 5- Nathanael Greene Herreshoff about 1876 G. L. Hurd, Providence, RI. Herreshoff Marine Museum Archives.

Towing Model Tests

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

We have always understood that unique to torpedo boats, and in advance of setting the preliminary hull design, Nat conducted open-water towing model tests (conducted in quiet water of a harbor or bay rather than a towing tank) of a series of hull shapes to define the best form to meet or better the guaranteed contract speed requirement of the Navy contract. In fact, ten of these towing models survive to today and we have a 1915 photograph of a test. What we did not know is whether that testing was done for every torpedo boat design.

Towing model testing was new in the 1870s. William Froude (1810-1879) began his work towards defining the laws of ship resistance in 1851 with tests conducted on the River Dart and a lake at Kenswick England. In 1868 dissenting from a report by an influential committee that “knowledge from model tests could not be trusted”, Froude asserted, “I contend that unless the reliability of small-scale experiments is emphatically disapproved, it is useless to spend vast sums of money upon full sized trials, … unless the ground is thoroughly cleared beforehand by an exhaustive investigation on small scale.” Froude’s work led to development of England’s first model experiment tank in 1871.[27] Then in 1873 the British Admiralty funded comparative towing tests of the 173-foot HMS GREYHOUND and a 1/16 scale model clearly demonstrating the validity of Froude’s laws of comparison.[28]

[27] Sir Wescott Abell, K.B.E. MEng. “William Froude, M.A., L.L.D., F.R.S. A Memoir” contained in The Papers of William Froude, 1810-1879. (The Institution of Naval Architects, London 1955) Pg. xii.

[28] William Froude, “On Experiments with HMS GREYHOUND, March 26, 1874” Papers of Froude, INA 1955. Pgs. 232-250.

In the George A. Converse Collection, DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist Univ. is an undated scrap of paper written in Nat Herreshoff‘s hand as follows:[29]

[29] George Albert Converse papers and photographs, 1861-1897 MSS 0068 Box 1, Folder 10 DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University

“Date of Model Towing Experiments

1876. Before designing LIGHTNING

October and November 1880 before designing STILETTO and others

November 1895 before designing #6 and 7 (i.e. PORTER & DuPONT)

August 1896 before making decision for 30 knot torpedo boat.”

We believe this scrap was provided to Converse in May 1897 to assist him in preparing a written defense of the PORTER (TB-6) Navy Acceptance Trial results against Navy Bureau attack. (To be covered in Part 6 of this Series; PORTER & DuPONT: Herreshoff Performance vs Navy Bureau Mediocrity.) In that letter to Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt, Converse described the towing model testing and speed performance of LIGHTNING:[30]

[30] George Albert Converse papers and photographs, 1861-1897 MSS 0068 Box 1, Folder 4 DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University

“In 1875 I was detailed as the Inspector of the Torpedo Boat “Lightning”, which the Navy Department had ordered to be built by the Herreshoff Mfg. Co. Prior to commencing the construction of this boat, Mr. N. G. Herreshoff made a series of experiments with models, towing them under conditions which would demonstrate the power required for propulsion, the form of hull best suited for speed, and determine other qualities which the boat should possess. These experiments were, at that time, complete and satisfactory; and the “Lightning”, built on the model then selected, developed a speed more than one statue mile in excess of the requirements; --and a speed which, up to the present time, has never been equaled by a boat of the same ‘waterline’ length.”

We have not found the LIGHTNING towing model tests in Nat’s records. There is reason to believe they were simpler than the 1880 tests conducted after Nat had been to England, joined the Institute of Naval Architects and obtained Froude’s papers. (The 1880 model tests will be covered in Part 4 of this Series.)

LIGHTNING’s Performance

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

The 58-foot LIGHTNING was delivered to the Torpedo Station on June 1, 1876 and immediately included in the June to August annual summer torpedo officer course of instruction. At the end of which the officers demonstrated operating LIGHTNING with her torpedo gear and electric light. When not employed at the school, LIGHTNING was used in experimentation of equipment and tactics. This included various spar torpedo configurations, a new mission of attacking at high speed with a towed torpedo, and signaling experiments using its electric light. LIGHTNING’s extreme maneuverability- as fast astern as ahead- stop in two ship lengths- and propeller located at center amidships offered greater probability of successfully swinging a towed torpedo into the target hull with less chance of fowling the tow line in its own propeller. Within a very short period LIGHTNING and these operations faded into the background eclipsed by the development of the automobile torpedo.[31]

[31] “BuOrd Report October 2, 1876” contained in Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 1876. Pgs. 123-24. Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 1877. Pgs. 24-5. “BuOrd Report November 1, 1877” contained in Secretary Annual Report 1877. Pg.190. Discussion of advantage in towed torpedo attack, LT Frederick H Paine USN ““Torpedoes for Attack and Defense of Vessels with an Opinion of Those in Use, and a Suggestion for a New Plan”. Contained in Report of The Secretary of the Navy Beginning of the Third Session 45th Congress, Washington GPO 1878. Pgs. 123-128,

Probably LIGHTNING’s most important run was the day in late August 1876 when LT Converse took ADM Porter at full speed twice around Coasters Harbor Island. “The visitors have never seen anything like it before.” reported the Newport Daily News. More importantly it informed Porter about Herreshoff and their aggressive pursuit of technology development.[32]

[32] Porter’s trip in LIGHTNING reported in Newport Daily News, Aug. 29, 1876.

How good was LIGHTNING as a spar torpedo boat and how did it compare with the world’s best at that time?

The U.S. Navy spar torpedo boat mission was to provide harbor and near coastal defense from attack on short notice. With low freeboard, machinery was constantly subject to salt corrosion. The boats could not be left in the water for long periods. They were stored in boat houses with ready launching by marine railway. LIGHTNING because of its extremely light weight of 6900 lbs. was particularly easy to store and launch. Once launched no other torpedo boat could beat LIGHTNING’s time to raise steam and be underway.

As for speed the US Navy view is that LIGHTNING’s specification was set at 19 mph- one mph better than the best at that time. Therefore, in Converse’s words, by achieving 20.33 mph in acceptance trials LIGHTNING developed “a speed which, up to the present time, has never been equaled by a boat of the same ‘waterline’ length.”

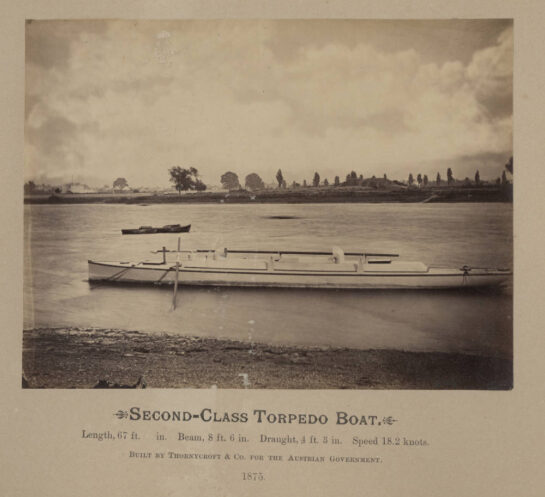

Another way is to compare LIGHTNING with boats of the world’s leading torpedo boat builders Thornycroft and Yarrow in England, and Normand in France. They each built for their own navy and a significant export market. Wight in England also built small torpedo equipped launches. Thornycroft delivered the first purpose-built torpedo boat to Norway in 1873. Designed for deploying a towed torpedo it was 57 ft. long, displaced 7½ tons and achieved 14.97 knots. Yarrow followed in 1875; Normand was later.[33]

[33] Lieut. G. E. Armstrong, late R.N. Torpedoes and Torpedo Vessels. (London, George Bell & Sons, 1896) Part of the Royal Navy Handbooks, edited by Cmdr. C. N. Robinson, R.N. Pgs. 165-6.

In 1875 BuOrd provided Converse information on a recent Thornycroft torpedo-launch built for Austria (Figure 7) and this information is in the Converse Collection at SMU together with a newspaper description of an 1875 Yarrow torpedo boat delivered to Argentina. Both designs are contemporary to LIGHTNING and were available to Converse and Herreshoff at the time. As shown in Table A LIGHTNING compares well with the Thornycroft and Yarrow boats.

Table A Comparison 1875 Spar Torpedo Boats

Vessel | DISPLACEMENT | LENGTH | BEAM | DRAFT | CONTRACT SPEED | TRIAL SPEED |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

LIGHTNING | 6900 lbs (boat with permanent fittings only) | 58 ft | 6 ft 3 in | 22 in aft (boat with permanent fittings only) | 19mph for one hour (16.72 kts) Continuous: 16-16.5 mph | 20.33 mph for one hour (17.89 kts) |

Thornycroft Second Class TB | 67 ft | 8 ft 6 in | 4 ft 3 in | 15 kts for one hour | 18.202 kts | |

Yarrow | 55 ft | 7 ft | 70 miles in 5 hours | 12.5 kts |

Vessel | BOILER | ENGINE/ ELECTRICS | HP | PROPELLER | SPAR TORPEDOES | HULL CONSTRUCTION |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

LIGHTNING | Safety coil boiler operating with sea water, 140 psi | Two 5” D x 10” stroke Single stage. Separate 12 HP engine for electrics | 60 hp | 2 bladed 3 ft 2 in D; 5 ft P | Handling equipment for one 30 lb. dynamite spar torpedo each side; 22 ft spars | Wood frames and planking |

Thornycroft Second Class TB | Fire tube locomotive type? | Hi pressure condensing | Handling equipment for one 25 lb. dynamite spar torpedo each side; 38 ft spars | |||

Yarrow | Fire tube, locomotive type, 150 psi working pressure | High pressure non-condensing engine/Battery | 60 hp | 3 bladed 3 ft 3 in D; 3 ft 6 in P | One 60 lb. dynamite on 25 ft spar | Iron frames and plating |

[34] All data from Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy 1876, (Wash DC GPO 1876. Pgs. 135-142. Includes Official US Navy trial of May 24, 1876, specifications and detailed “as built” description of the boat and its machinery.

[34] Data from Thornycroft photo of “Second Class Torpedo boat built for Austro-Hungarian Government 1875” & “Fast Torpedo Launches” reprint from Engineering, September 17, 1875. Both documents provided to Torpedo Station Newport by BuOrd letter Nov. 5, 1875 to assist in the design of the spar torpedo handling equipment for LIGHTNING. Source; George Albert Converse Papers and Photographs, 1861-1897. DeGolyer Library, SMU.

[36] Yarrow Data from “Torpedo Steam Launch” London Times, Feb. 1, 1875. Built for Argentine government. Believe this information was available to Converse and Herreshoff in early 1875. Source; George Albert Converse Papers and Photographs, 1861-1897. DeGolyer Library, SMU.

A Win for the Herreshoff System

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

The invention of the coil boiler and the widespread publicity of the performance of VISION and LIGHTNING was a major win and attracted new private, commercial and navy business for what became known as “the Herreshoff System”. What it did not do is result in any follow-on purchase of high-speed launch-type torpedo boats as the US faced no imminent foreign threat to its harbors.

John’s annual delivery of steam powered vessels immediately increased five-fold to in excess of ten per year continuing into 1884, when Nat introduced the water level square boiler. As Nat acknowledged in 1934, it was the good prospects of building the steam business (then 100% coil boilers) that enticed him to join John to form the Herreshoff Manufacturing Co. (HMCo) in late 1877.[37]

[37] Nathanael G. Herreshoff, “Some of the Boats I have Sailed In”. Recollections. Herreshoff Marine Museum, Bristol RI 1998. Pg. 52.

LIGHTNING put Herreshoff on the world map as viewed by US and foreign navies. The annual summer cruise of Annapolis cadet engineers added Herreshoff to an itinerary that already included the Newport Torpedo Station and Corliss in Providence.[38] The U.S. Navy ordered various launches. Englishman George R. Dunell spent time in Bristol before selling HMCo launches and torpedo boats to both the British Admiralty and the Russian Navy. The French Navy came calling. John started the practice of making his latest vessel available in Bristol to the U.S. Navy’s Board of Naval Engineers, (Steam Engineering Experimentation Board) led by Benjamin Isherwood for conduct of trials as the Navy wished, within reasonable time limits. The reports were re-printed and reported in the press.

[38] Summer cruise visits to HMCo are documented in the Practice Ship reports contained in the Secretary of the Navy Annual Reports

As expressed in the 1881 report of the 100-foot, 250 hp, steam yacht LEILA (HMCo #40) the Board came to understand from its visits to Bristol, and the inspections and trials that it conducted, that Herreshoff built “remarkable steam yachts” because they had developed a system referred to as the “Herreshoff System of Motive Machinery” and the “Herreshoff System of Steam Yachts”. The vessels built by this system featured:[39]

[39] Discussion of the Herreshoff System derived from Isherwood, Zeller & Magee. "Report of a Board of United States Naval Engineers on the Herreshoff System of Motive Machinery as Applied to the Steam-Yacht Leila, and on the Performance of that Vessel." Washington, Bureau of Steam Engineering of the U.S. Navy Department, 1881.

- • Lightness of hull & machinery

- • Excellence in design, material, workmanship

- • Speed

- • Extreme rapidity to raise steam

- • Safety- freedom from accidents

- • Progressive development & improvement

Delving further into the LEILA Report:

- 1. Hull proportions are ascertained from a number of accurate experiments so that resistance due to hull form is minimized. Resistance as a function of speed does not increase in a higher ratio than the theoretical one of the square of the speed.

- 2. HMCo has no superior in their ability to construct steam yachts of the lightest weight. Such yachts are a specialty and the subject of exhaustive experiments.

- 3. Everything is engineered. The light weight is compensated by excellence of material and fastener selection, design and workmanship and it is by a combination of these that the Herreshoff yachts are produced with as great strength and durability as found in much heavier hulls.

The 70-Foot Herreshoff Harbor Torpedo Boat

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

James A. Garfield on assuming the presidency in March 1881 tasked his new Secretary of the Navy William H. Hunt to work toward an expansion and modernization of the Navy. Hunt exhorted Congress that without action the Navy would soon “dwindle into insignificance”, it was their duty to see that the Navy did not “perish” but was “restored to a condition of usefulness.” He set out to build a nucleus of a modern Navy that could be enlarged in an emergency. To provide Congress with a plan meeting the general approval of the different branches of the Navy and to avoid the failed schemes and theories of the past he appointed an advisory board. The Board made up of officers of recognized ability and experience, included some not yet having reached the highest ranks but selected from those who would command the new ships. The 15-member Board headed by RADM John Rodgers, included two representatives each from BuC&R and BuSteam. Isherwood was one of the BuSteam representatives.[40]

[40] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. Washington GPO 1881 Pgs. 3, 5, 6.

The job of the Board was to provide a report advising:[41]

[41] Ibid. Pgs. 27-8

- 1. Number of vessels to be built

- 2. Class, size, & displacement

- 3. Material form of their construction

- 4. Nature & size of the engines and machinery for each

- 5. Ordnance & armament for each

- 6. Appropriate equipment for each

- 7. Internal arrangements of each

- 8. Probable cost of each vessel complete & ready for service

Among their recommendations for torpedo vessels, they specified: -For strict channel and harbor service ten steel vessels of the type known as the Herreshoff harbor torpedo boat; about 70 feet long, max speed not less than 17 kts. Cost per vessel complete and ready for service $25,000. [42]

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

In effect without a design from Herreshoff but based upon the Navy’s continuing up-to-date knowledge and confidence in the latest product of the Herreshoff System, they were ready to leave the decisions to Nat Herreshoff, depending upon the proven “progressive development & improvement” of the “Herreshoff System”.[43]

[43] We have found no half model or design for such a torpedo boat in the 1881 period of the Herreshoff records.

The result was the same as before- no imminent threat, therefore no contract to build.

What Next

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

In Part #4 we discuss the founding of the Herreshoff Manufacturing Co, Nat Herreshoff’s development as an engineer, his inspection of the British torpedo boat HM LIGHTNING and the US Navy’s acquisition of STILETTO (WTB-1).

[1] Richard S. West Jr. The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter. (New York: Coward McCann, Inc. 1937) Pgs. 315-18.

[2] New York Herald reported in first 48 hours more general orders were issued then in the previous two years. Paul Lewis, Yankee Admiral (A Biography of David Dixon Porter). (McKay Co. New York 1968). Pg. 183.

[3] Sloan, Benjamin Franklin Isherwood Naval Engineer. Pgs. 228-41.

[4] Thomas Wildenberg and Norman Polmar. Ship Killers: A History of the American Torpedo. (Annapolis, MD, USNI Press, 2010) pgs. 16-17.

[5] Ibid., pg. 17

[6] “Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy, George M. Robison, Dec. 3, 1869.” House of Representatives 41st Congress 2nd Session; Message of the President of the United States with Reports of The Postmaster General and of The Secretary of the Navy, (Washington GPO 1869) Pgs. 14-15

[7] Providence Evening News Aug. 24, 1870. Recounts a reporter’s ride in ANEMONE. This is not to imply that John did not advertise his vessels along much of the Atlantic coast. He conducted publicized demonstrations in New York City, Norfolk Navy Yard, Savannah, and the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. See “Advertising the Herreshoff Way”, Curator Log, October 2013.

[8] Tamara Moser Melia “David Dixon Porter: Fighting Sailor” from James C. Bradford, Editor, Captains of the Old Steam Navy: Makers of the American Naval Tradition 1840-1880. (Annapolis, MD; Naval Institute Press 1986). Pg. 242.

[9] The David Porter and David Dixon Porter Papers, 1803-1889 are housed in the Manuscript Division, William L. Clements Library, Univ. Of Michigan. (www.clements.umich.edu). In the collection is a 200+ Page document titled “My Career in the Navy Department”. It is bound with string & is too fragile to photocopy or scan. It has not been indexed. What that may add to the story we do not know.

[10] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. (Washington GPO 1881) Pg. 5.

[11] “Navy Appropriation Bill” Army and Navy Journal, January 28, 1871. “The Torpedo Boat (ALARM) Launched”. New York Herald November 13, 1873. “INTREPID recently launched.” Army and Navy Journal, July 18, 1874. “Torpedo Boats ALARM & INTREPID”, Report of Adm Porter Wash. Nov. 7, 1874 contained in 43rd Congress Beginning of Second Session; Report of The Secretary of the Navy, (Washington GPO 1874) pgs. 204-20.

[12] West, The Second Admiral, Pgs. 325-336.

[13] “Admiral Porter’s Big D”. Newport Aug. 5. Army and Navy Journal, Aug. 11, 1888.

[14] Report of Adm Porter Oct 22, 1873. Contained in 43rd Congress Beginning of First Session; Report of The Secretary of the Navy, (Washington GPO 1873) Pg. 276.

[15] Quote on publicizing torpedo developments from Report of Adm Porter Wash. Nov. 7, 1874 contained in 43rd Congress Beginning of Second Session; Report of The Secretary of the Navy, (Washington GPO 1874) Pg. 216.

[16] “BuOrd Annual Report Oct. 17, 1872”. Contained in 42nd Congress Beginning of Third Session; Report of The Secretary of the Navy, (Wash. DC GPO 1872). Pg. 54.

[17] James B. Herreshoff letter to Nathanael G. Herreshoff dated April 19, 1874. Nathanael G. Herreshoff Correspondence Folder 25; Herreshoff Model Room Archive Boxes. Access courtesy Halsey C. Herreshoff.

[18] Jeannette Brown Herreshoff, The Early Founding and Development of the Herreshoff Manufacturing Company. Rinaldi Printing Co. Tampa FL, 1949. Pages are not numbered. (Available Herreshoff Marine Museum archives) Quote is from an 1872 letter from Nat to James thanking him for the material.

[19] John B. Herreshoff letter to Nathanael G. Herreshoff dated May 29, 1874. Nathanael G. Herreshoff Correspondence Folder 25; Herreshoff Model Room Archive Boxes. Access courtesy Halsey C. Herreshoff.

[20] Nathanael G. Herreshoff, Recollections. Herreshoff Marine Museum, (Bristol RI 1998) Pg. 92 describes the meeting on Sept. 24, 1874. Contemporary news articles include; “Salt Water for Boilers“. Providence Evening Press, Sept. 7, 1874. Torpedo Station report on VISION demonstration is contained in K. R. Breese, Letter to U.S. Chief BuOrd Capt. William N. Jeffers.] Newport, R. I., October 25, 1875. In: Annual Official Report of the Secretary of the United States Navy. (Wash. DC, 1876.) Pgs. 134-5.

[21] “Bureau of Steam Engineering Annual Report Oct. 31, 1872”. Contained in 42nd Congress Beginning of Third Session; Report of The Secretary of the Navy, (Wash. DC GPO 1872). Pgs. 129-36.

[22] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy on the Operations of the Department for the Year 1876, (Washington GPO 1876) Pgs. 134-142.

[23] Secretary Annual Report 1876. Pgs. 110-16, 118-124,

[24] Capt. K. R. Breese USN, Inspector Ordnance, in charge of Station ltr. Nov. 23, 1876 to Chief BuOrd. Secretary Annual Report 1876. Pg. 134.

[25a] Secretary Annual Report 1876, Pg. 135-37.

[25b] G. W. Baird, Passed Assistant Engineer USN, Comments to paper S. H. Leonard, Assistant Engineer U.S. Navy, Paper X; “Tubulous Boilers” Journal of American Society of Naval Engineers Vol 2, 1 May 1890. Pg 391.

[26] Surviving LIGHTNING design material in the Nathanael G. Herreshoff Collection, access courtesy of Halsey C. Herreshoff, include seven (A-G) sectional sketches dated Nov. 1875, undated volume curve calculations, weight calculations & the half model. Missing are the preliminary profile sketch and the final construction drawings.

[27] Sir Wescott Abell, K.B.E. MEng. “William Froude, M.A., L.L.D., F.R.S. A Memoir” contained in The Papers of William Froude, 1810-1879. (The Institution of Naval Architects, London 1955) Pg. xii.

[28] William Froude, “On Experiments with HMS GREYHOUND, March 26, 1874” Papers of Froude, INA 1955. Pgs. 232-250.

[29] George Albert Converse papers and photographs, 1861-1897 MSS 0068 Box 1, Folder 10 DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University

[30] George Albert Converse papers and photographs, 1861-1897 MSS 0068 Box 1, Folder 4 DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University

[31] “BuOrd Report October 2, 1876” contained in Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 1876. Pgs. 123-24. Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 1877. Pgs. 24-5. “BuOrd Report November 1, 1877” contained in Secretary Annual Report 1877. Pg.190. Discussion of advantage in towed torpedo attack, LT Frederick H Paine USN ““Torpedoes for Attack and Defense of Vessels with an Opinion of Those in Use, and a Suggestion for a New Plan”. Contained in Report of The Secretary of the Navy Beginning of the Third Session 45th Congress, Washington GPO 1878. Pgs. 123-8,

[32] Porter’s trip in LIGHTNING reported in Newport Daily News, Aug. 29, 1876.

[33] Lieut. G. E. Armstrong, late R.N. Torpedoes and Torpedo Vessels. (London, George Bell & Sons, 1896) Part of the Royal Navy Handbooks, edited by Cmdr. C. N. Robinson, R.N. Pgs. 165-6.

[34] All data from Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy 1876, (Wash DC GPO 1876. Pgs. 135-142. Includes Official US Navy trial of May 24, 1876, specifications and detailed “as built” description of the boat and its machinery.

[35] Data from Thornycroft photo of “Second Class Torpedo boat built for Austro-Hungarian Government 1875” & “Fast Torpedo Launches” reprint from Engineering, September 17, 1875. Both documents provided to Torpedo Station Newport by BuOrd letter Nov. 5, 1875 to assist in the design of the spar torpedo handling equipment for LIGHTNING. Source; George Albert Converse Papers and Photographs, 1861-1897. DeGolyer Library, SMU.

[36] Yarrow Data from “Torpedo Steam Launch” London Times, Feb. 1, 1875. Built for Argentine government. Believe this information was available to Converse and Herreshoff in early 1875. Source; George Albert Converse Papers and Photographs, 1861-1897. DeGolyer Library, SMU.

[37] Nathanael G. Herreshoff, “Some of the Boats I have Sailed In”. Recollections. Herreshoff Marine Museum, Bristol RI 1998. Pg. 52.

[38] Summer cruise visits to HMCo are documented in the Practice Ship reports contained in the Secretary of the Navy Annual Reports

[39] Discussion of the Herreshoff System derived from Isherwood, Zeller & Magee. "Report of a Board of United States Naval Engineers on the Herreshoff System of Motive Machinery as Applied to the Steam-Yacht Leila, and on the Performance of that Vessel." Washington, Bureau of Steam Engineering of the U.S. Navy Department, 1881.

[40] Annual Report of The Secretary of the Navy November 28, 1881. Washington GPO 1881 Pgs. 3, 5, 6.

[41] Ibid. Pgs. 27-8

[42] Ibid. Pg. 37

[43] We have found no half model or design for such a torpedo boat in the 1881 period of the Herreshoff records.