April 2, 2020

From the Vault: the RELIANCE wheel (Part II)

What happened to RELIANCE after she won the Cup, and how did one of her wheels end up in Yonkers?

If you haven't read Part I, you can check it out here!

What happened to Reliance?

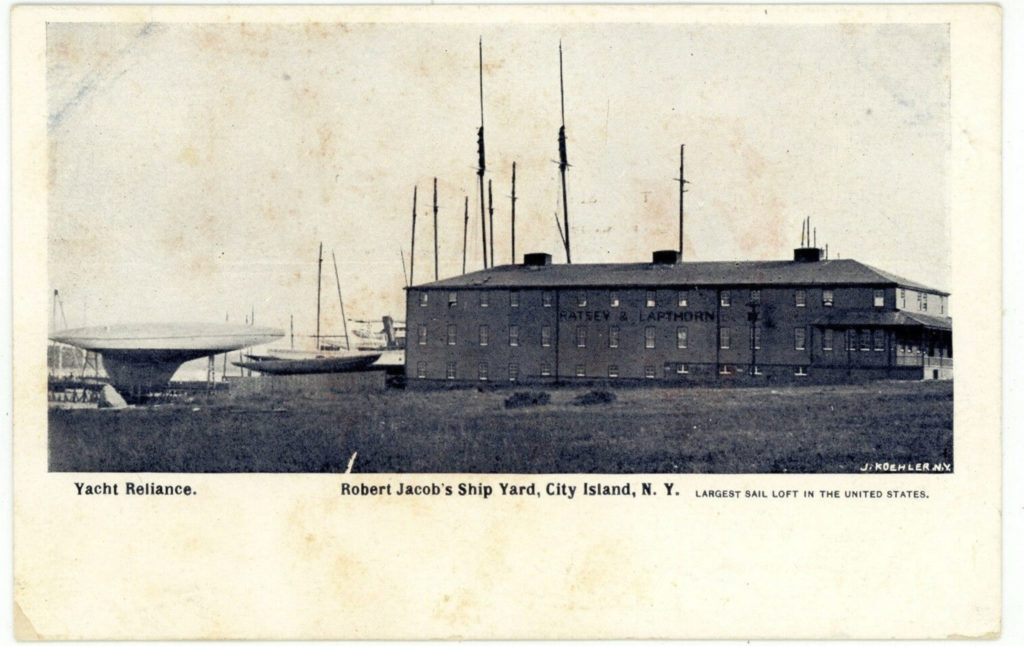

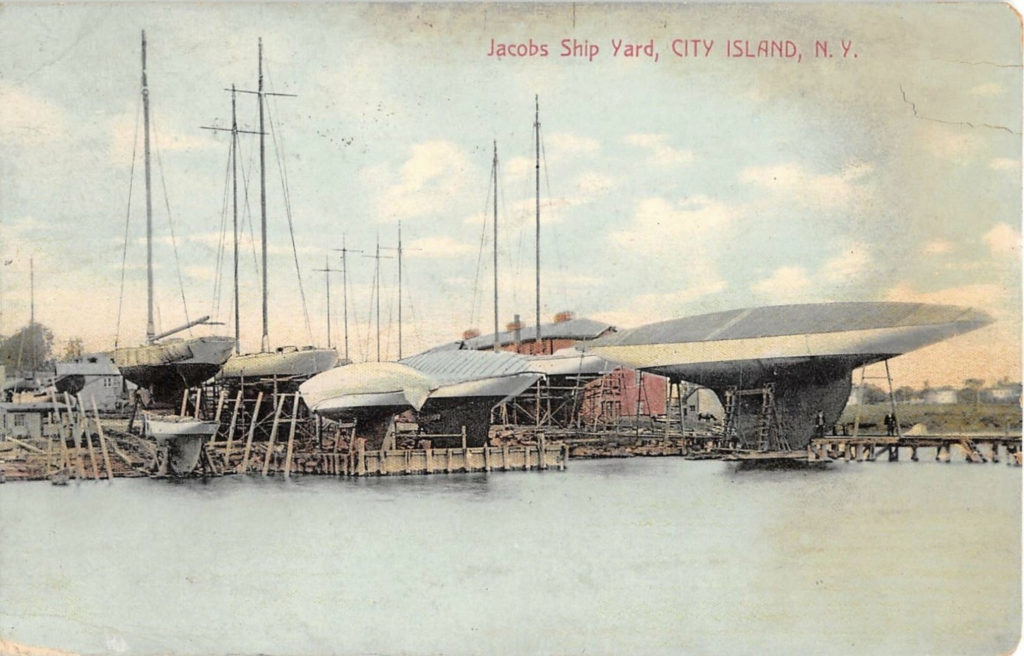

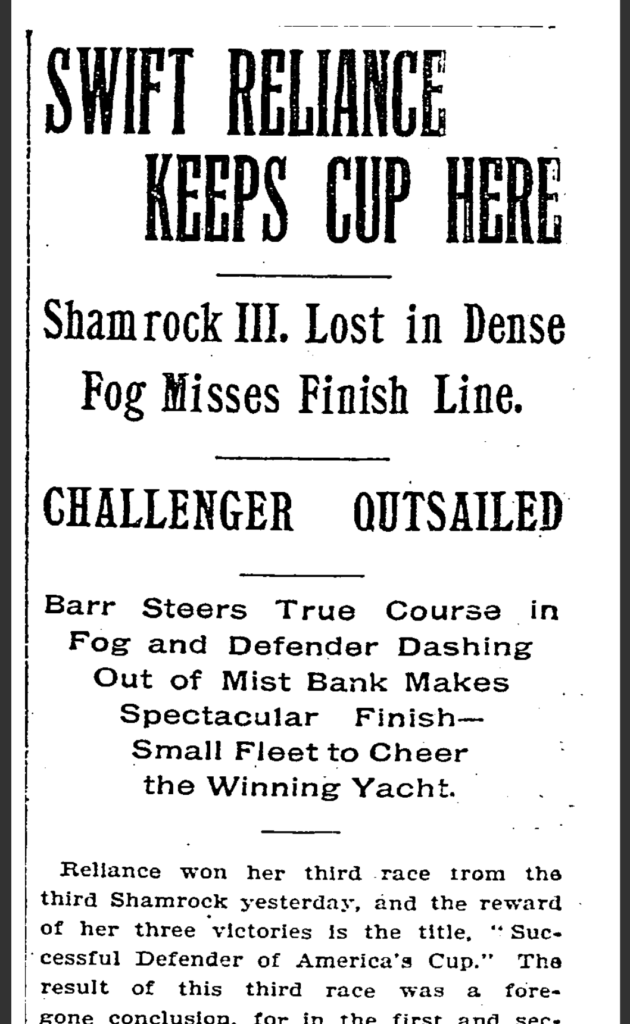

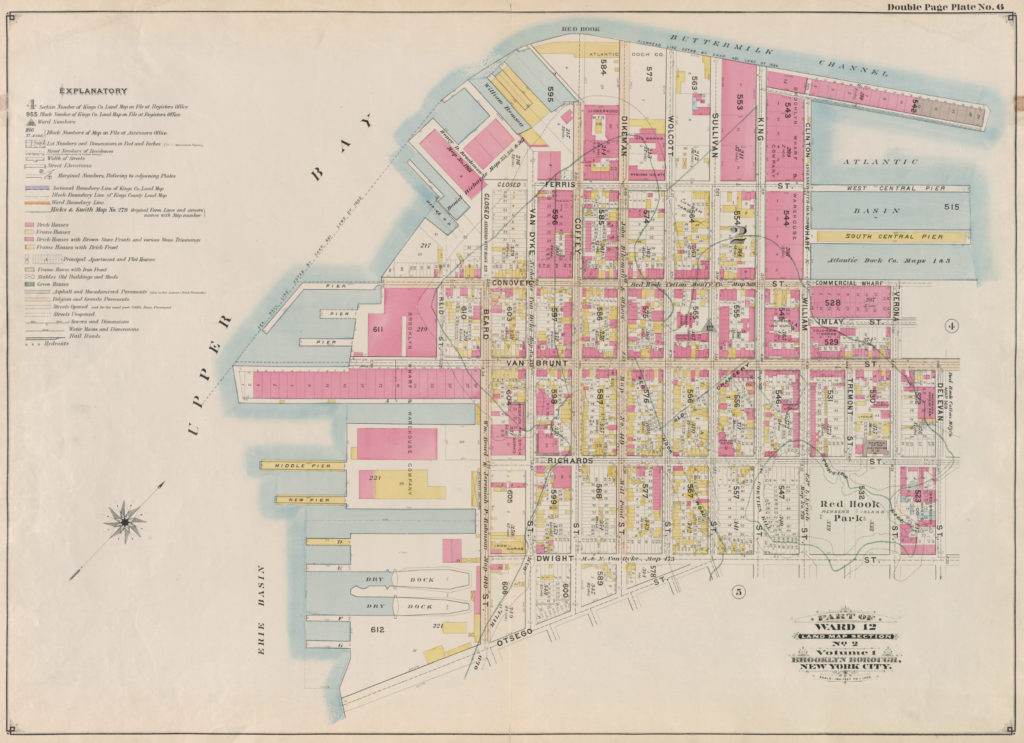

RELIANCE handily won every race against Thomas Lipton’s SHAMROCK III in August and September of 1903, and kept the Cup for the Iselin Syndicate and the New York Yacht Club. After the racing was over, there wasn’t much of a future for RELIANCE, unlike some other former America’s Cup contenders and candidates that continued to race or were converted to yachts. As Yachting magazine reported in 1914, RELIANCE was “too big for a sloop, with no one in her class to sail against, and not suited or conversion into a schooner… [so] she stood idle in Jacob’s yard [on City Island] for eleven years, a club over any would-be challenger for the Cup…” She was finally sold for scrap in December 1913 to a Brooklyn-based ship wrecker and salvor named Michael Cowhey, who had RELIANCE towed from City Island to Robins Dry Dock and Repair Company at Erie Basin in April 1914. He began dismantling the Cup Defender around the corner from Robins at the Furman Dry Dock Company in July that year.

Michael Cowhey...

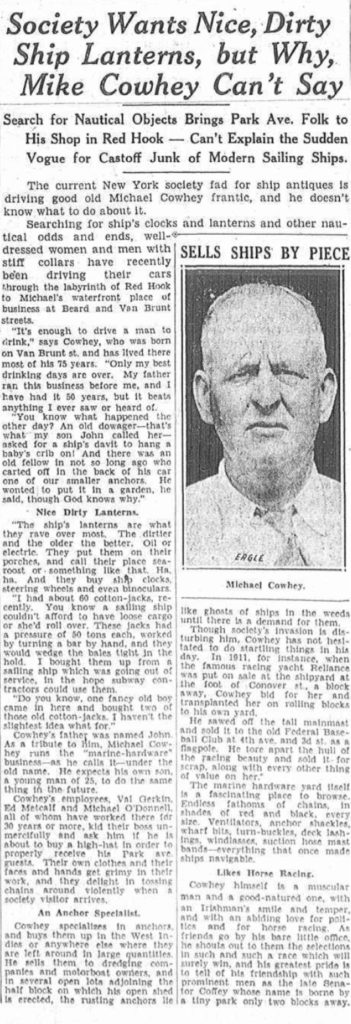

By all accounts, Cowhey was a colorful figure on the Red Hook waterfront. The business at 438-440 Van Brunt St. he had inherited from his father had started out as a scrap iron and marine hardware salvage business - but as the great shipping days waned, nostalgia turned his shop into an exotic destination for “New York Society” decorators. In an entertaining (and error-riddled) article from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1929, Cowhey reports that “ships lanterns are what they rave over the most. The dirtier and the older the better. Oil or electric, they put them on their porches, and call the place Searoost, or something like that. Ha, ha. And they buy ship clocks, steering wheels and even binoculars…” ! It’s hard to imagine an equivalent fad today, but we wonder if Mr. Cowhey wasn’t far more delighted at the business than genuinely driven to drink by the interest from “fancy old boys,” as claimed in the article.

RELIANCE's acres of sails were cut up and sold for awnings and sail covers, and the valuable metal (lead, bronze, aluminum, and steel) was sold for scrap. According to a 1914 New London Day article, after Cowhey purchased RELIANCE he sold her mast to the Federal Baseball Club (home of the Brooklyn Tip-Tops) at 4th Avenue and 3rd Street in Brooklyn for $1,000 - something like $25,000 today adjusted for inflation. It remained at Washington Park as a flagpole until it was purportedly destroyed by a lightning strike in 1921. What happened to the rest of the hardware - and the wheels - is not well documented, but the location of Cowhey's shop and the yard where RELIANCE was scrapped provide some clues.

And Mr. Todd

Erie Basin is just down the block from Cowhey’s shop. RELIANCE first arrived in Brooklyn to be measured in dry dock at Erie Basin on June 5, 1903. At the same time, a 46-year-old William H. Todd was working his way up the management ladder at Robins Dry Dock and Repair Company. Todd had been hired as a foreman / master mechanic there in 1896, after previously working at the Brooklyn Navy Yard as a master ship fitter, and as an apprentice before that for Pusey and Jones in his home-state of Delaware. By 1909, he would be the president of Robins - and in 1916 he established the Todd Shipbuilding Corporation, which would eventually include not only Robins but also Tietjen and Lang in Hoboken, Tebo Yacht Basin Company, the Clinton Dry-docks Inc., the Quintard Iron Works, the White Fuel Engineering Corporation, two Todd shipyards on the west coast in Tacoma and Seattle, and two others in Louisiana and Alabama. (Check out the Hoboken Historical Museum online collections for some great Todd Shipyards artifacts!) It was an incredible achievement in a short amount of time, with a total of seven plants across the country netting more than $6.5 million in profits annually by 1919.

One wonders if the up-and-coming Todd too fell prey to nostalgia when RELIANCE returned to Erie Basin to be destroyed in 1914, eleven years after her first visit. Here she had once been a source of such intrigue, celebration and public curiosity. Cowhey would have recognized the collectible value of an item like a ship’s wheel from as famous a vessel as RELIANCE. If anyone were placed to make him an offer for it, the astonishingly successful Todd was a good candidate, though we can’t guess at the price.

We have not found any documentation or correspondence relating to a sale, but the circumstances of Todd’s life and work put him close enough to RELIANCE’s scrapping for us to believe he is the same Todd of the plaque still fixed to the Yonkers wheel today, and that it is possible he acquired it from Cowhey. Another piece of evidence that supports this theory (and not that the wheels were removed sometime in the 11 years preceding the scrapping) is the provenance documentation of the Mystic Seaport’s RELIANCE wheel: a letter from the donor in 1954 states that his (the donor’s) father had been given the wheel as a gift by the owner or manager of the yard where RELIANCE was scrapped. We don’t yet know whether this was Todd himself the manager or owner of the Furman Dry Dock Company, but are in search of any evidence that the donor’s family was connected with Todd.

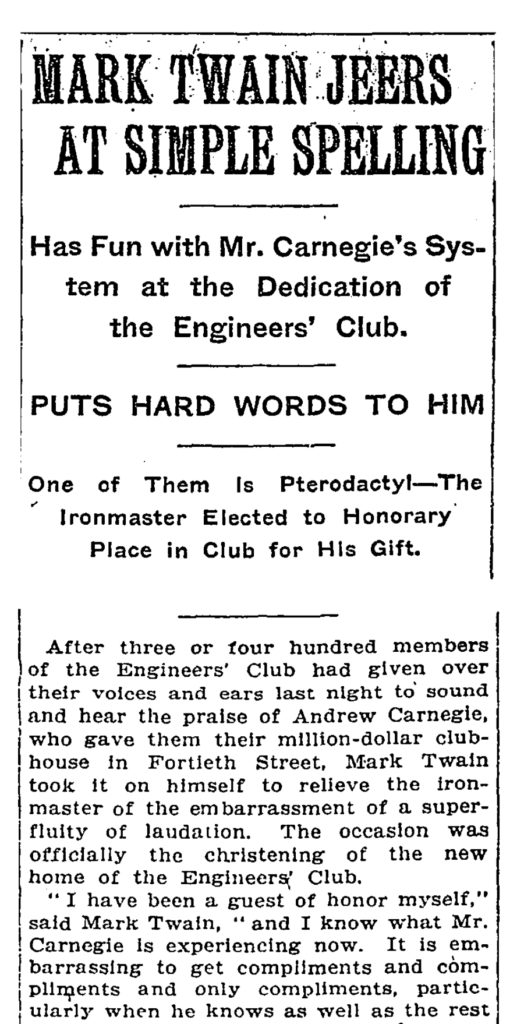

What was the Engineers Club?

So, we have William H. Todd in the right place at the right time. But what is (or was) the Engineer’s Club? The Engineers Club was a social club “composed of engineers and others who may be interested in or connected with the engineering profession,” according to the Club constitution. The Club boasted eminent members such as Andrew Carnegie, Nikola Tesla, Thomas Edison and President Herbert Hoover. The Club was established in December 1888, and had several temporary clubhouses in the NYC. In 1904, they made the front page of the New York Times when Carnegie committed $1.5 million for a dedicated clubhouse on West 40th St., when building social clubs in the City was particularly in vogue. The building opened in 1907 at 54 West 40th St., facing Bryant Park with much fanfare, and Mark Twain roasted Carnegie at the dedication ceremony. The club had a library and an art committee, rooms to socialize in, a restaurant, and overnight accommodations.

Todd was a trustee of the Engineers’ Club beginning in 1916. Incidentally, he also became a member of the New York Yacht Club on December 21st of that year, which begs the question: why would he present the wheel to the Engineers’ Club over the NYYC, the sponsor of the RELIANCE syndicate? Logic would suggest that he presented the wheel to the Engineers’ Club before he became a member of NYYC, which would place the donation into a window between 1914 when RELIANCE was scrapped, and December of 1916, when he was elected into the NYYC. Or perhaps Todd, occupied as he was in business with dry docks, graving docks and marine rails, saw RELIANCE as more of a marvel of engineering than a yacht and therefore this relic was better placed at the Engineers club. We will probably never know his motivations, but it is interesting to speculate while we continue to research.

How did it end up in Yonkers?

Honestly, we're still not sure! The Engineers Club experienced a serious fire in December of 1919, which damaged the 12th and 13th floors. They struggled during the Depression, and foreclosed on a second clubhouse and golf course in Roslyn on Long Island, which had first opened in 1917. (Today it is a private country club that still operates under the Engineers Club name, but ceased to be affiliated with the Manhattan based club after the foreclosure in 1933). Membership dwindled through the 1950s and 1960s as the generation of wealthy industrialists of the Golden Age thinned, and in 1978 the New York Times announced a number of paintings from the Engineers’ Club would go up for auction. The 32 West 40th St. clubhouse was vacant by 1979. Today, the club still stands, but all that remains of the Engineers is a commemorative plaque facing Bryant Park. In 2007, the building was added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. Today, it is part residential co-op and part retail space, but the facade retains its historic character.

We are still looking for more information about how the wheel might have arrived in Yonkers from the Engineers’ Club, but it could have been any time up until the Club’s closure in 1978 - 1979 or shortly thereafter. Our best guess at present is that it was sold in the late 70s or early 80s, and eventually ended up as part of a restaurant's maritime themed decor, the significance of the words on the plate and engraved hub lost for a time. Admittedly, much of this post is conjecture, and we will continue to search but may never know more than we do now. We hope you have enjoyed learning a bit more about the suspected players, and how we begin to approach uncovering the provenance of such a significant artifact. And if anyone knows where the papers or archive of the Engineers’ Club have ended up - drop us a line! And we’ll keep you posted when (or if) we learn more.