April 16, 2020

Curator’s Log June 2019: The Story of NC-4

Curator’s Log June 2019: Centenary of the First to Fly the Atlantic: The Story of the NC-4 Introduction In May 1919 the Navy Flying Boat NC-4 completed the first Transatlantic … Continue reading Curator’s Log June 2019: The Story of NC-4

Curator’s Log June 2019: Centenary of the First to Fly the Atlantic: The Story of the NC-4

Introduction

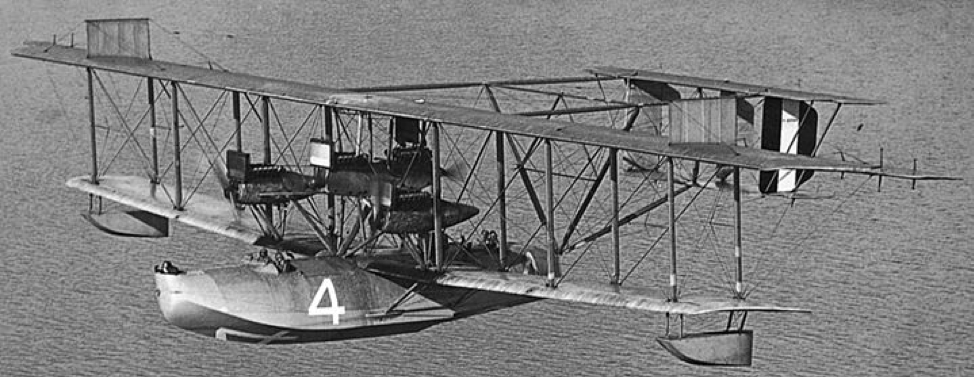

In May 1919 the Navy Flying Boat NC-4 completed the first Transatlantic flight covering a distance of 1380 miles in a little over 15 hours from Newfoundland to the Azores. The accompanying NC-1 and NC-3 failed in the attempt. Charles Lindbergh speaking of his 1927 solo transatlantic flight to Paris said, “I had a better chance of reaching Europe in the Spirit of St. Louis than the NC boats had of reaching the Azores. I had a more reliable type of engine, improved instruments and a continent instead of an island for a target. It was skill, determination and a hard-working crew that carried the NC-4 to the completion of the first transatlantic flight.”1 This is the story of the NC-4 whose hull was constructed by the Herreshoff Manufacturing Co. (HMCo) in one of the first instances of building a design other than one created by Nathanael Greene Herreshoff.

Sources

To simplify the telling there is a bibliography of the primary sources for the Log. Endnotes are limited primarily to Herreshoff construction of the hull. Most of the manuscript material other than Annual Reports of the Navy Department are housed in the museum’s NC-4 curator folder.

All figures are US Navy images.

Developing Naval Aviation

From its very beginning in summer 1914 the war in Europe demonstrated no military arm was complete without aviation; which for the navy meant scouting, locating mine fields and later when the US entered the war the pressing need to locate and destroy submarines. US naval aviation was in its infancy; in April 1914 four scout planes had supported operations in Mexico; the first Secretary appointed aviation board had just recommended establishing a naval air station and flight school in Pensacola, FL. and the purchase of 50 aircraft (they had 12). In the short-term orders were attempted with foreign suppliers until the government and US manufacturers could produce reliable aircraft engines (at the time referred to as “motors”) in horsepower’s up to 200 as would be required for Navy flying boats. The foreign aircraft were never delivered.

In 1915 the 63rd Congress made the first ever appropriation ($1M) for a “Naval Air Service”. Orders were placed with Curtiss Aeroplane Co. and others for hydroplanes (land and take -off from the water). The Bureau of Construction and Repair ( Bu C&R) established an aircraft design division, initiated aircraft manufacture at the Washington Navy Yard where model testing (aircraft, wings, wing fabrics, hulls, floats, pontoons) was being conducted at the model basin (in-water) and new experimental wind tunnel (in-air). The Bureau of Steam Engineering (Bu Steam) established an aircraft motor division that was actively working with others to solve the many motor problems that were hindering the development of larger, longer range aircraft. Curtiss and other manufacturers started deliveries of aircraft to Europe including two types of flying boats.

The Buildup of naval aviation was slow because “practically every American aero plane manufacturer Is primarily a builder of land machines and has not considered the special problems of naval airplanes.” This began to change when the 64th Congress appropriated $3.5M; enough money for manufacturers to start thinking about investing in the problems of naval aviation. In FY 1917 Congress for the first time approved a three-year naval program. A federally mandated Aircraft Production Board assumed oversight of all aircraft production and development of the Liberty series of high-powered aircraft engines.

When the United States entered the war in 1917 the Navy had 45 aviators and 50 seaplanes. With the war came unlimited funding. Within a year there were 823 naval aviators, 100 seaplanes for patrol and 324 for training. Success with the high-powered Liberty engine allowed development of the flying boat for coastal patrol. Federal policy dictated that the government should not rely exclusively on private industry for all its aircraft needs. A Naval Aircraft Factory (NAF) was established at the Philadelphia Navy Yard beginning production in Oct. 1917. A navy survey of flying boats in service in Europe selected the British modified Curtiss H-16 (96-foot wing span; 45-foot length, two Liberty engines) for production. The first H-16 flew March 1918, 228 days after factory groundbreaking. Facing an increased production demand for 1918 an assembly facility was added to the NAF to assemble parts subcontracted to private industry. Herreshoff built and delivered hulls for ten H-16s (HMCo hull 346-355) and ten Curtiss/British designed F-5Ls (104-foot wingspan, 49-foot length, two engines) (HMCo hulls 356-365) to NAF.

But first came NC-4 (HMCo hull 341).

The NC Program

In September 1917, RAdm David. W. Taylor, Chief Bu

C&R directed his engineers to develop concepts for a long-range flying boat;

a lightly-built craft with maximum useful load capacity for bombs and depth

charges. It would be the largest flying

boat with a wing spread of 126-feet (equivalent to a Boeing 707) and capable of

transatlantic flight, avoiding the sea voyage as deck cargo as was done with

the two-engine flying boats then in production. He envisioned this as a rapid

paced development program building the four aircraft in as little as three

months. The selected design was a lightweight three-engine, two-wing

configuration with a short hull and high tail, supported by booms and cable

well clear of the water.

The Idea of transatlantic flight first gained public attention in 1913 when the London Daily Mail offered 10,000 pounds for the first flight from the North American continent to any point in Great Britain or Ireland. Glenn Curtiss who had long dreamed of being the first in this endeavor was contracted by American department store executive, Rodman Wanamaker, to build the large flying boat America. It was in trials when the war began in Europe. Sold to Britain as a prototype it was the catalyst for cooperative Curtiss/British design efforts that led to the H-16 and F-5L.

To make use of Curtiss’ experience his company was contracted to complete the new design and prepare the detail plans. The two navy engineers, who had developed the concept (recent graduates of an aeronautics course at MIT) were sent to work at the Curtiss Buffalo plant. This cooperative effort resulted in the flying boat designation NC, for “Navy Curtiss”.

Things did not work out as Taylor envisioned. In the fall of 1917, with the preliminary design 50% complete, new studies concluded that with the Liberty engines then available the NC could not make the 1900-mile Newfoundland to Ireland flight. The shorter Newfoundland to Azores route was the fall back. Then in Dec. 1917, in approving the NC construction contract, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels did not endorse the NC as “urgent”. Rather he directed it was “not to interfere with production in progress”. This loss of priority slowed the schedule.

The construction plan envisioned much of the components to be subcontracted for assembly at a new, small Curtiss factory in Garden City Long Island. To speed getting the first plane NC-1 into the air, Curtiss built the hull; Lawley was contracted for hulls of NC-2 & 3; Herreshoff for NC-4. Completed aircraft were moved for testing to the Rockaway Long Island naval air station where a new marine railway was installed for launch and recovery.

The NC-1 made its first flight on Oct. 4, 1918 and shortly set a record by carrying 51 passengers aloft; an odd number because one was a stowaway. The joy of accomplishment was tempered by the latest design assessment- the three-engine NC-1 had insufficient power to take-off with the fuel load required to reach the Azores. Then came November 11 and war’s end; the rush was over, but wait- the London Daily News renewed its transatlantic challenge.

Enter naval aviator John Towers (In 1914 he had been he had been the navy representative monitoring the development of Curtiss’ flying boat America.) effectively lobbying for a transatlantic flight by the NCs as an “epoch-making event” to enhance the reputation of naval aviation. Subsequently endorsed by a naval board, Towers later assumed command of NC Seaplane Division 1 with responsibility for the mission. On Feb 4th a target date of May 1 was set for the NCs to depart Rockaway. By then the ice in Newfoundland would have broken up and the overnight flight to the Azores could enjoy a full moon. There was another cause for urgency as a British team was preparing a modified bomber for a Newfoundland to Ireland crossing.

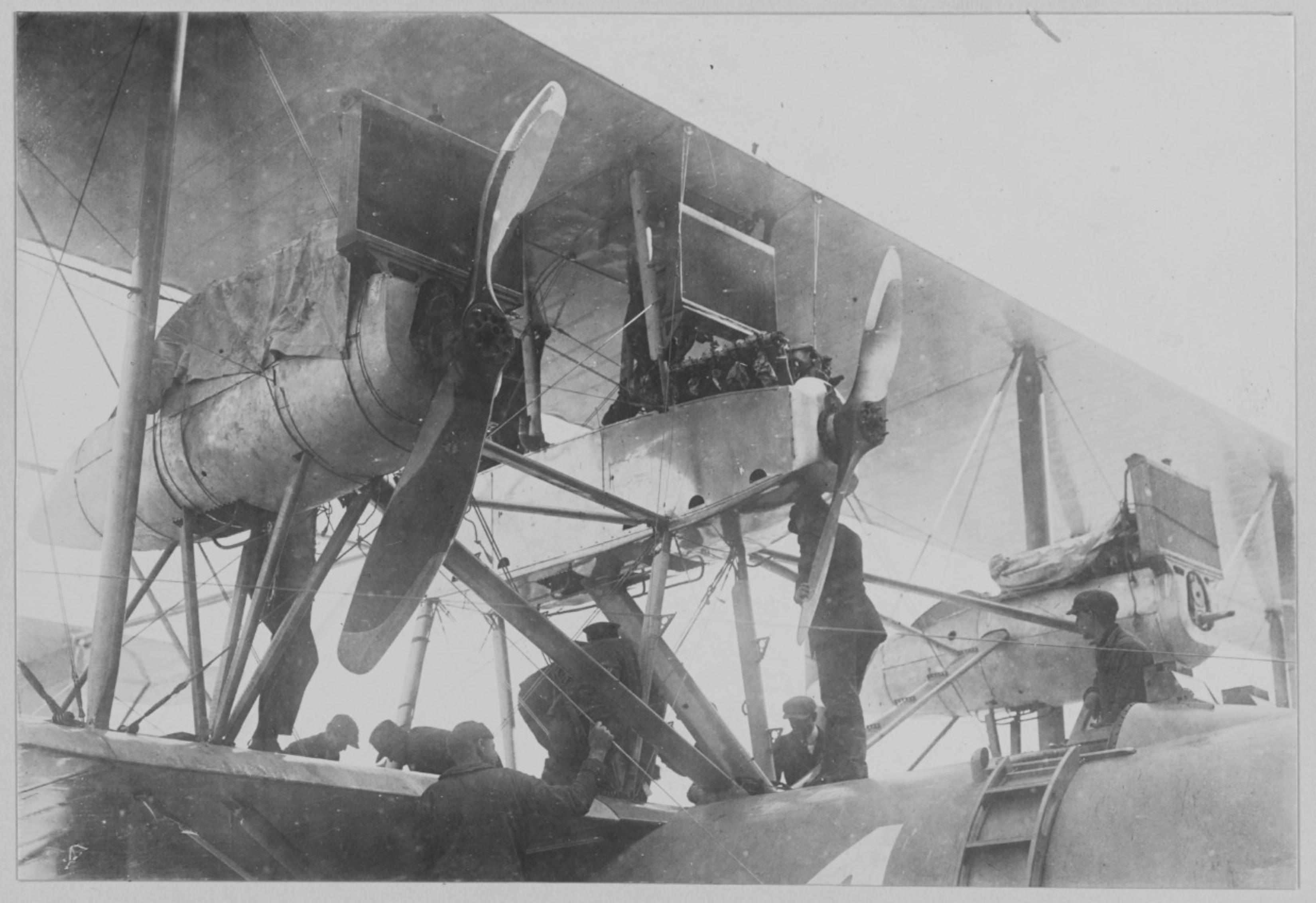

With a renewed mission changes were made to NC-1; NC-2 was built to the lessons-learned and NC-3 and 4 were held up until problem solutions were confirmed. The 12-cylinder Liberty engines were changed to a new high compression 400 hp model and a 4th engine was added by changing the center nacelle to a front “puller” and an aft “pusher” engine. On April 30, NC-4, the last in line, was completed. Then the Division experienced a series of setbacks resulting in damage to NC-1, 2 and 4. When the flying boats took off for Halifax at 10 AM on May 8 there were just three- NC-1, 3, and 4; the latter having conducted possibly only one test flight. Two-part Figure 2 illustrates the NC-4 as configured in May 1919.

Constructing the Hull of NC-4 (HMCo hull no. 341)

(See Figures 3, 4 & 5 for external views of the hull)

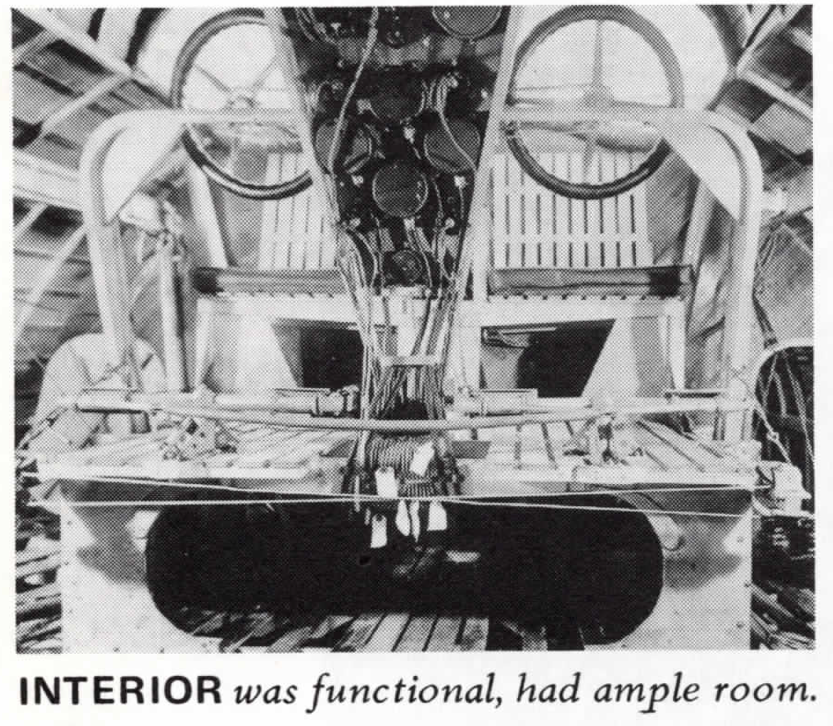

The NC hull was a complex structure. It had to withstand rough sea landings, support the external loads of the wings, engines and tail structure as well as the internal weight of crew, equipment and 1800 gallons of gasoline. Contained within the 44-foot 9-inch x 10-foot hull were six compartments divided by five two-ply mahogany transverse bulkheads spaced along a keel of Sitka spruce, and these main members joined by stringers of ash. Each bulkhead had small port and starboard watertight doors for access. The compartments and positions of the six-man crew: 2, 3

- Nose occupied by aircraft commander/navigator

- Cockpit for two pilots (See Figure 6 for internal view of the cockpit and structure.)

- Four-200 gal. aluminum fuel tanks

- Four-200 gal. aluminum fuel tanks

- One -200 gal. aluminum fuel tank, radio, radio operator, engineer, & mechanic

- Tail containing the radio direction finder with its box like antenna

There were several wind-driven auxiliaries. Four windmills pumped gasoline from the 200-gallon tanks to a 90-gallon service tank in the upper wing. A wind generator powered the radio.

In the records I have found three descriptions of the hull structure, differing primarily in the types of wood used, structure of the turtleback (aka deck) and other details.

- “Dimensions and Characteristics of NC

Seaplanes” Annual Reports of the Navy Department for the Fiscal Year 1919. Wash GPO 1920. P

231-232.

- “Main keels of boat hulls are of oak or rock elm. (Note- rather than Sitka spruce as in paragraph above.) Hull structure is in general of spruce. Planking is of spruce or cedar. Turtleback covering is of cedar or of cottonwood birch three-ply veneer.”

- Richard K. Smith First Across: The US Navy’s

Transatlantic Flight of 1919. Naval institute Press. Annapolis MD 1973. P.

25-26.

- Planking along the V-bottom was two-ply Spanish cedar varying from 5/16 to 7/16 inch; the two-plies glued together with a fine cotton muslin. The lower sides of hull were ¼ inch two-ply mahogany.

- The curved upper deck (aka turtleback) was one-course 3/32-inch white cedar covered by cotton duck fabric glued to the planking.

- Harry Town of HMCo descriptions of the structure

- Harry Town 1969 Interview. At that time the sole surviving of those that built NC-4 hull. On occasion 50th anniversary of flight held at Smithsonian with Harry Town & Tom Brightman as invited guests.; and

- Carlton Pinheiro. NC-4 Address Bristol

Rotary & Punta Delgada Rotary at HMM Dec. 4, 1998. Containing information

as told to him by Harry Town

- Keel Sitka spruce, as was planking. Laminated double planking 45 degrees forward and 45 degree aft, fastened with copper and painted gray. For water tightness and to keep planking thin, muslin set in marine glue between plies.

- Double-planked mahogany hull with muslin and shellac between the two. (HMCo used shellac rather than glue in double-planked topsides of cruising sailboats.)

- Steam bent ash used to finish off cockpit opening.

It seems likely that the description in the Navy’s 1919 annual report is the hull as built by Curtiss for NC-1, and the description by Smith and Harry Town apply to the hull as built for NC-4. It is very doubtful the turtleback of NC-4 was a three-ply veneer.

On Dec. 31, 1917 Ernest E Adler, Superintendent of the Herreshoff wood department went to the Curtiss Plant, Garden City accompanied by teenage son Albert, returning with the hull blueprints after two days at the plant. The hull was built in the small boat shop by a six-man crew; Ernest Alder, Peter Gaspar, Fred Hodgdon, Herbert F. Newman and Harry Town are the names we know. When completed early January 1919 the end of the building had to be removed to extricate the hull. Young Albert Adler helped to move the hull with the workboat Useful to the Bristol railroad depot at the foot of Franklin street. On lifting the hull from the boat, the crane contacted a 600-volt power line. Fortunately, the hull was not damaged. 4

Curtiss built NC-1 in nine months, the hull being the longest element of the construction process. We have no information on HMCo’s building schedule, but it is likely they were held up by design changes or awaiting NC-1’s first flight in Oct. 1918. The hull was difficult to build because of its complex shape with a reverse curvature in the forward underbody. (See hull body sections in Figure 2 & hull views Figures 4, 5 & 6) Herbert Newman remembered only Herreshoff “followed the plans exactly”; Curtiss and the other builder “made variations here and there…just looking at the NC-4 hull, I’d know she’s the Herreshoff job because she is different from the others in the bow.” 5

There is another critical element to building a flying boat to maximize carrying capacity; that is applying strict weight control in building the structure. The design weight of the hull bare of internal fittings was 2400 lbs. Data below shows all missed the mark. The experienced Curtiss crew was the lightest, the 2nd Lawley shows them coming down the “learning curve” and HMCo with only one, is slightly heavier than Lawley’s 1st. 6

| Hull | Builder | Weight lbs | Over weight | % |

| NC-1 | Curtiss | 2583 | 183 | 7.6 |

| NC-2 | Lawley | 2787 | 387 | 16.1 |

| NC-3 | Lawley | 2700 | 300 | 12.5 |

| NC-4 | HMCo | 2825 | 425 | 17.7 |

NC-4 Transatlantic Flight

There are many exciting stories of the flight in the bibliography and on-line. This short account is taken from the official reports by the NC flying boat commanders contained in the Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy for the FY 1919; Appendix G Trans Atlantic Flight. They illustrate the truth of Lindbergh’s comments expressed in the Introduction.

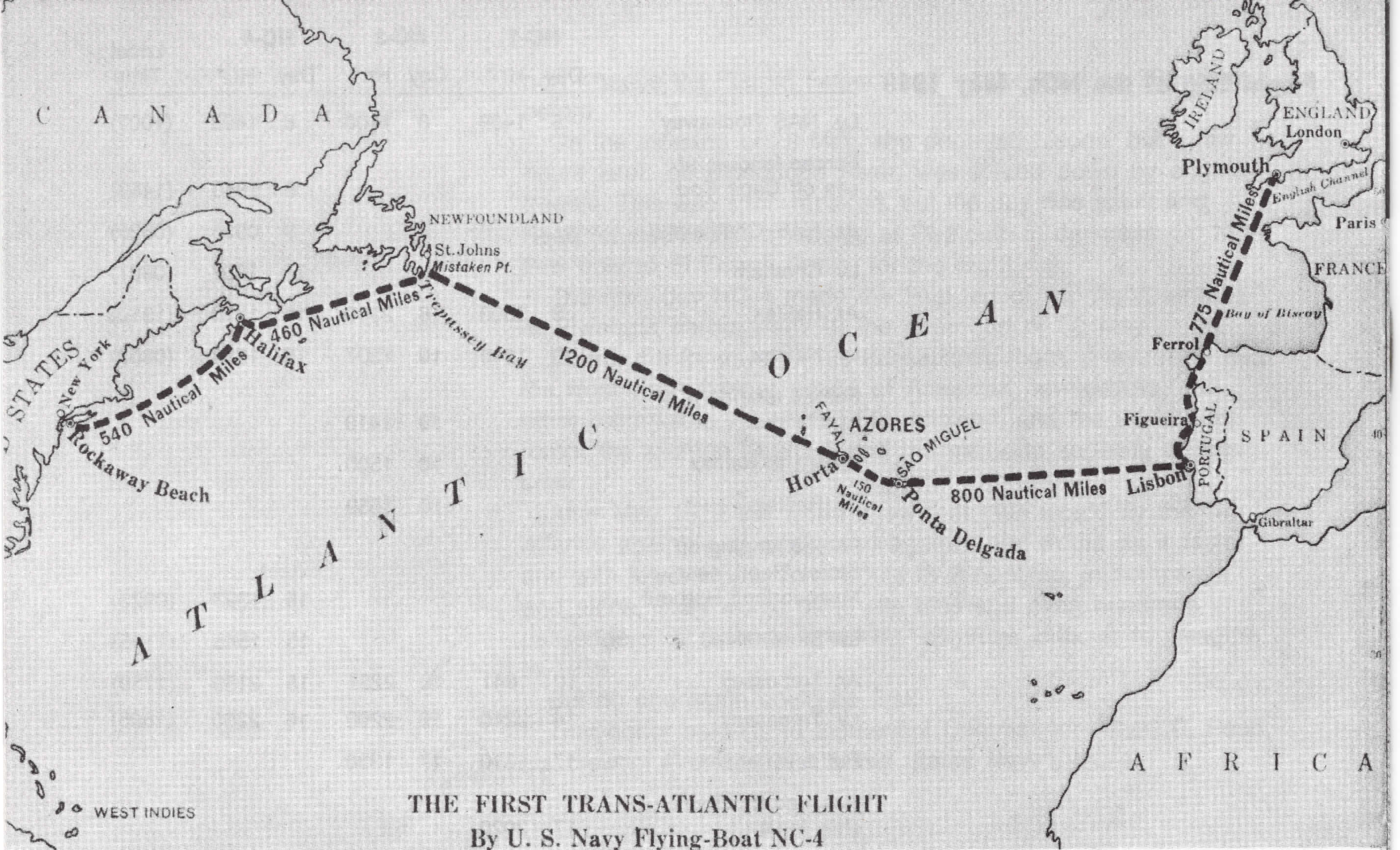

The 4500-mile journey (see Figure 7) started with a flight from Rockaway to Halifax, Nova Scotia; on to Trepassey Bay Newfoundland; the long 1400-mile transatlantic journey to Punta Delgada, Azores; then shorter legs to Lisbon and finally Plymouth, England. The navy mobilized 68 destroyers to be stationed at intervals of 50-75 miles along the route as guide posts, to take meteorological observations, report the weather and render assistance in the event of a water landing.

The flight of LCDR Albert C. Read and his five-man NC-4 crew, went amiss short of four hours when a drop in oil pressure forced shutdown of the center aft engine. Continuing on three engines for another hour, a connecting rod failed in the center forward engine. Unable to remain airborne they landed 80 miles east of Cape Cod. Failing to raise a destroyer by radio, NC-4 taxied to the Chatham Naval Air Station where they replaced the center forward engine with what was available - a low compression model. After experiencing one more oil pressure drop and quick landing for repair, NC-4 caught up with the others in Trepassey where weather had prevented a start for the Azores. Here they swapped the center forward engine for a high compression type. (See Figure 8 Assembling Engines in NC-4.)

All three departed Trepassey about 6 PM on May 16. Twenty-one destroyers were on station along the line of flight. NC-4, experiencing no engine problems, landed in Horta, Azores the next morning some 170 miles short of Punta Delgada. Flying above the 1400-foot fog layer NC-4 was able to follow the line of destroyers by radio and direction finder. Unable to contact the last destroyer in the line they landed at Horta.

NC-1 and 3, lost in dense fog and unable to contact the destroyers were forced to land on the sea. Heavy seas caused extensive damage to NC-1 and she sank, with all hands saved, after a failed towing attempt by a Greek steamer. NC-3 drifted and taxied for 53 hours in gale force winds, her crew spending hours riding the upper wing to balance the craft, before arriving at Punta Delgada,

After further weather delays and a few engine problems NC-4, on May 31, 1919, made a symbolic landing at Plymouth, England from whence the Pilgrims had sailed three centuries before.

Flight Times & Miles NC-4

- Rockaway to Halifax 621 miles 8 hours 54 minutes

- Halifax to Trepassey 529 miles 6 hours 23 minutes

- Trepassey to Horta 1380 miles 15 hours 13 minutes

- Horta to Punta Delgada 172 miles 1 hour 45 minutes

- Punta Delgada to Lisbon 920 miles 9 hours 43 minutes

- Lisbon to Plymouth 891 miles 12 hours

- Total 4513 miles; total flight time 53 hours 58 minutes

Postscript- The Bousquet Model of NC-4

In 1969 NC-4 was on display at the Smithsonian for the 50th anniversary of its transatlantic flight. The Navy sent a young photographer, Don Bousquet, to record the event. Don later became involved in making model planes. in 1995 he obtained plans for the NC-4 and built a flying model that he donated to the museum. It is on display in the Model Room. 7

John Palmieri

Bibliography

- Annual Reports of the Navy Department for FYs 1914- 1919 including reports of the Secretary, Chief of the Bureau of Construction and Repair (C&R), and Chief of the Bureau Steam Engineering (Steam). FY 1919 Report Appendix G Trans Atlantic Flight. Source for development of naval aviation, aviation design and production plans, strategies, and results; NC program, NC Transatlantic flight official reports, dimensions and characteristics of NC flying boats.

- Peter Andrews, Navy Air; 75 Years of Naval Aviation, American Heritage, New York,NY 1986. Source NC transatlantic flight.

- Richard E. Byrd, Admiral US Navy, Skyward,. G. P. Putnam & Sons New York. 1928. Source development of navigation equipment for NC transatlantic flight.

- David Crocker, “The Forgotten Flight of the NC-4” Presentation at Chatham MA on transatlantic flight anniversary. Source NC program, NC flying boat arrangements and structure, NC transatlantic flight.

- HMCo employee interviews, letters and statements about building the NC-4 hull by those who either built, or were knowledgeable about the hull construction

- NC and NC-4 newspaper articles from 1919, the 20th (1939) and 50th (1969) anniversaries of the transatlantic flight. Source transatlantic flight and HMCo employee accounts of construction the NC-4 hull.

- Carlton J. Pinheiro, Curator Herreshoff Marine Museum (HMM). NC-4 news articles, presentations, HMM Chronicle.

- Richard K. Smith First Across: The US Navy’s Transatlantic Flight of 1919. Naval institute Press. Annapolis MD 1973. Pages 22-27. Source NC program, NC hull design and construction details, NC hull weights.

- William F. Trimble, Hero of the Air: Glenn Curtiss and the Birth of Naval Aviation. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD. 2010. Source Glenn Curtiss, Curtiss airplanes, Curtiss Engineering Corp., development of naval aviation, NC program and NC design.

1. Commander Ted Wilbur, The First Flight Across the Atlantic, May 1919. NC-4 50th Anniversary Committee, Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum Wash DC 1969. P 6.

2. Richard K. Smith First Across: The US Navy’s Transatlantic Flight of 1919. Naval institute Press. Annapolis MD 1973, P. 25-26.

3. David Crocker “The Forgotten Flight of the NC-4” Presentation at Chatham, MA, date uncertain

4. Albert E. Alder letters of March 7, 1979 and April 23, 1979

5. George E. Pelletier, Journal Aviation Editor, “Six Men in a Boat That Could Fly”. The Providence Sunday Journal, May 31, 1939

6. Smith. P. 24

7. Stephen Heffner “In a Model World, the NC-4 Flies Again” The Providence Journal-Bulletin Oct 16, 1995 pp C1-C2.